Introduction

The Cathedral Church of Christ, Blessed Mary the Virgin and St Cuthbert of Durham, commonly known as Durham Cathedral and home of the Shrine of St Cuthbert, is a cathedral in the city of Durham, England. It is the seat of the Bishop of Durham, the fourth-ranked bishop in the Church of England hierarchy.

The present Norman era cathedral had started to be built in 1093, replacing the city’s previous ‘White Church’. In 1986 the cathedral and Durham Castle were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Durham Cathedral’s relics include: Saint Cuthbert’s, transported to Durham by Lindisfarne monks in the 800s; Saint Oswald’s head and the Venerable Bede’s remains.

The Durham Dean and Chapter Library contains: sets of early printed books, some of the most complete in England; the pre-Dissolution monastic accounts and three copies of Magna Carta.

From 1080 until 1836, the Bishop of Durham held the powers of an Earl Palatine. In order to protect the Anglo-Scottish border, powers of an earl included exercising military, civil, and religious leadership. The cathedral walls formed part of Durham Castle, the chief seat of the Bishop of Durham. There are daily Church of England services at the cathedral, Durham Cathedral Choir sing daily except Mondays and holidays, receiving 727,367 visitors in 2019.

Durham Cathedral is the greatest Norman building in England, perhaps even in Europe. It is cherished not only for its architecture but also for its incomparable setting. For this reason it was inscribed together with the Castle as one of Britain’s first World Heritage Sites.

Located on a bend in the River Wear is Durham Cathedral, a Norman building designed in the Romanesque style. The Cathedral was built between 1093 and 1133 in order to house the relics of St. Cuthbert and the Venerable Bede. It is said that St. Cuthbert posthumously chose the location. His coffin was rendered immovable in that very bend of the River Wear and there, the Shrine of St. Cuthbert was built and later, to house the Shrine, the Durham Cathedral was erected.

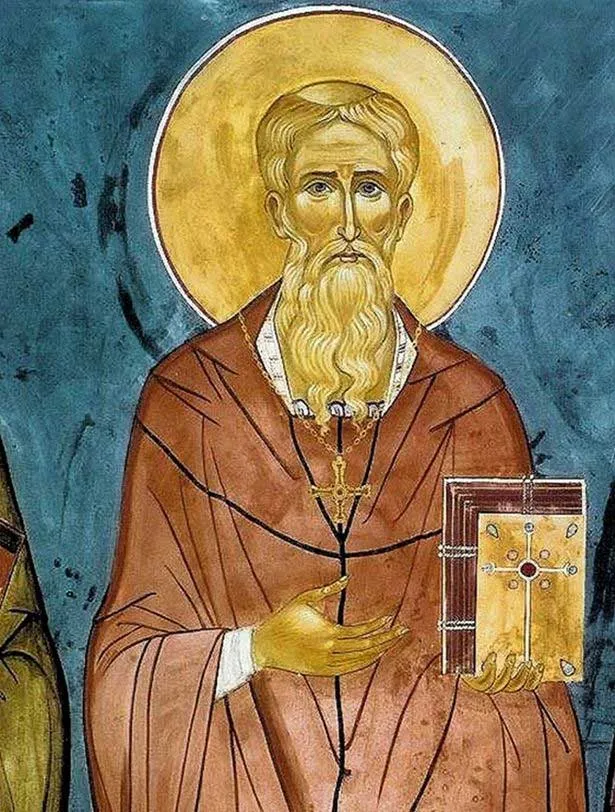

Cuthbert, the Bishop of Lindis Farne, England, was dedicated to a life of prayer and missionary work. Towards the end of his life, he retired to a hermitage on Farne Island. It was after his death in the in A.D 687 that his legacy truly flourished. Our St. Cuthbert Cross, based on the saint’s original 6th century pectoral cross, celebrates the saint and his legacy.

Many miracles have been attributed to St. Cuthbert after his death. St. Cuthbert was sought out for his posthumous healing abilities. Many people made pilgrimages to the shrine at Saint Cuthbert in Durham Cathedral to be cured of sickness and ailments while others reported being miraculously healed after praying at one of the many churches dedicated to the saint throughout Great Britain.

Unfortunately, the original, elaborate shrine of St. Cuthbert no longer exists. The marble, bejeweled shrine was destroyed in the Reformation and replaced in 1542 by the simple marble slab marked ‘Cuthbertus’.”

Durham Cathedral is considered to be England’s finest example of Norman architecture. Unlike other Norman buildings, which over the years were heavily modified, Durham Cathedral remains relatively untouched and unchanged, save the addition of two chapels and a central tower. It is the oldest surviving building with a stone vaulted ceiling of such a large scale.” This was a great innovation at the time, when such large ceilings and roofs were chiefly made of wood.

Today, Durham Cathedral holds over 1,700 services a year. “The Cathedral has been in continuous use since its original construction 900 years ago. It remains a place of worship and pilgrimage, and is also an important visitor attraction.” Many people visit the shrine to seek the saint’s blessing and healing powers.” Durham Cathedral is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site; a testament to the Cathedral’s architectural and historical significance.

History of Shrine of Saint Cuthbert in Durham Cathedral

It is said that Saint Cuthbert was the most revered saint in northern Europe before Thomas Becket was killed by the four knights in Canterbury Cathedral on 29th December in 1170. Cuthbert must have been a remarkable man for no other reason than Britain’s greatest treasure was written for ‘God, St Cuthbert and all the saints of the island’. This was, of course, the Lindis Farne Gospels, and they were written and decorated by Ead Frith, Bishop of Lindis Farne, before 720.

Saint Cuthbert was buried with great pomp according to the custom, and in his coffin were placed not only the St Cuthbert Gospel, but also a small portable altar and his pectoral cross above right. This delicate little jewel was made of gold and garnets, and is in remarkably good condition. Durham Cathedral Viking attacks made the monks move from Lindis Farne, and they took the Lindis Farne Gospels with other books and St Cuthbert’s coffin with them. The White Church at Durham was put up by the successors of those monks when it is said that St Cuthbert’s coffin stuck and refused to move any further.

This church was replaced by the Norman Romanesque building, started in 1093. Amazingly that building took only 40 years to complete. This was because much of the work was done off site. The magnificently decorated huge stone columns had their patterns cut into them away from the church building, and they were assembled in the cathedral, each pattern fitting neatly in to the one above. This is explained here. The best view of the cathedral must surely be from the railway, and it is a wonderful sight as the train slows down into the station to view the cathedral on its high hill opposite.

St Cuthbert’s Shrine itself is very plain and simple now, with a greenish stone slab and at floor level. A description of it as it was indicates that previously it was made of gilded marble. There were four spaces at the base where pilgrims could kneel to venerate the saint. The shrine was covered by a precious cloth (see below for a board painted according to a description of this cloth; this board now hangs over the tomb) and on special days this cloth would have been lifted so the coffin itself could be seen in all its glory.

It was not only his many miracles that mean that Saint Cuthbert was so revered. The story goes that when his coffin was elevated to the altar and it was opened, St Cuthbert’s hair had grown, there was flesh on his body and his joints were still flexible.

Durham Cathedral, In fact, this continued right up until the Reformation when Henry VIII’s commissioners in around 1539 came to smash faces on tombs and strip the church of its treasure. An eye witness gives this account: Dr Ley, Dr Henley and Mr Blythman brought with them a goldsmith who, when he had taken off the gold and silver and precious stones, climbed up to a chest strongly bound in iron. The goldsmith took a hammer and smashed open the chest. St Cuthbert was ‘lying whole with his face bare and his beard as if it had a fortnight’s growth’. In smashing the shrine the goldsmith said that he had broken one of the saint’s legs. He was told to throw the bones down, but replied that this was impossible because they were still joined.

Durham Cathedral, St Cuthbert is not the only saint here. Bede, often known as the Venerable Bede, is regarded by many as the father of English history. He was born in around 672, and lived and worked around Monk wear mouth (now Sunderland) and Jarrow. He entered the monastery at Monk wear mouth when he was seven, and was taught by Benedict Biscop, and later by Ceolfrith, the Abbot of the twin foundation. Bede wrote over 60 books, including a little of his own life contained in a chapter at the end of his Historia Ecclesiastica, (a history of the church in England).

Codex Laudianus, We do still have a book that is said to have been owned by Bede. This is a sixth-century Greek and Latin manuscript of the Acts of the Apostles. It’s called the Codex Laudianus and is now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Latin is on the left and Greek on the right. It is written in Uncials, similar to the St Cuthbert Gospel, but these letter-forms are not as fine.

Bede died on Ascension Day in 735 and was buried at Jarrow. It is likely that Bede’s remains were transferred to Durham in the eleventh century. His tomb was looted in 1541, but it is thought that the contents were probably interred in the Galilee chapel at Durham where his tomb now stands.

Architecture

Romanesque architecture, Gothic architecture, Norman architecture

Architects: George Gilbert Scott, James Wyatt, Anthony Salvin, Edward Robert Robson, Richard Farnham

UNESCO World Heritage Site inscription: 1986

There is some evidence that the aisle of the choir had the earliest rib vaults in England, as was argued by John Bilson, English architect, at the end of the nineteenth century. Since then it has been argued that other buildings like Lessay Abbey in northwest France provided the early experimental ribs that created the high technical level shown in Durham. There is evidence in the clerestory walls of the choir that the high vault had ribs. There is controversy between John James and Malcolm Thurlby on whether these rib vaults were four-part or six-part, which remains unresolved.

The building is notable for the ribbed vault of the nave, with some of the earliest transverse pointed arches supported on relatively slender composite piers alternated with massive drum columns, and lateral abutments concealed within the triforium over the aisles. These features appear to be precursors of the Gothic architecture of Northern France, possibly due to the Norman stonemasons responsible, although the building is considered Romanesque overall. The skilled use of the pointed arch and ribbed vault made it possible to cover far more elaborate and complicated ground plans than before. Buttressing made it possible to build taller buildings and open up the intervening wall spaces to create larger windows.

The UNESCO World Heritage Site description makes this comment about the architectural style:

Though some wrongly considered Durham Cathedral to be the first ‘Gothic’ monument (the relationship between it and the churches built in the Île-de-France region in the 12th century is not obvious), this building, owing to the innovative audacity of its vaulting, constitutes, as do Spire [Speyer] and Cluny, a type of experimental model which was far ahead of its time.

Another United Nations web site states that “the use of stone ‘ribs’ forming pointed arches to support the ceiling of the nave was an important achievement, and Durham Cathedral is the earliest known example” [and] The nave vault of Durham Cathedral is the most significant architectural element … because it marks a turning point in the history of architecture. The pointed arch was successfully used as a structural element for the first time here in this building. Semi-circular arches were the type used prior to the adoption of the structural pointed arch — the limitations of which is that their height must be proportionate to their width”.

Saint Cuthbert’s tomb lies at the east in the Feretory and was once an elaborate monument of cream marble and gold. It remains a place of pilgrimage. The fragments of St Cuthbert’s coffin are exhibited at the cathedral.

St Cuthbert’s Tomb

Back in the 19th century, the tomb of St Cuthbert, in whose name Durham Cathedral was built, was opened twice, under very different circumstances. Today, Exhibitions Assistant Shaun McAlister takes a look back over the first of these great historic moments.

On May 17th 1827, the cathedral librarian, James Raine, gathered with the Sub-Dean William Darnell, Prebend William Gilly and various stone masons and labourers to open the St Cuthbert’s tomb. He never asked permission of the Bishop, Dean or Chapter. His only motivation was to be able to prove that Cuthbert’s body was no longer incorrupt.

It was described as an effort ‘to open the eyes of the blind deluded papists to the imposture of their church’. James Raine was a brilliant librarian but terrible at public relations.

When the top cover was removed the team had to dig through a layer of earth and sand to reach the second grave cover. This one had been placed there in 1542 when Cuthbert had been reburied following the Reformation. Time and resources being in short supply, they reused the grave cover of a former monk, Richard Haswell, who had died in 1446. Once removed, they were able to see into the tomb.

The most recent coffin they discovered also dated back to 1542. It was heavily decayed with very few fragments salvageable. This drawing from the Cathedral archives by Raine shows how it would have looked when new. While the coffin no longer exists, the iron rings shown on the outside were saved.

When Raine and his team reached the final coffin, the one made in 698 and now on display in the Great Kitchen within the cathedral’s Open Treasure museum, they found the wrapped remains of St. Cuthbert. His body, now a skeleton, was wrapped in various silks and garments designed for the clergy. This drawing shows how Cuthbert looked when seen by Raine in 1827.

Although we refer to it as the Shrine of St. Cuthbert he isn’t the only one buried there. Among the bones shown at Cuthbert’s feet are skull fragments of St. Oswald, the martyred King of Northumbria. There are also bones of small children which we know from medieval relic lists were the remains of the Holy Innocent’s, children killed by Herod. The remaining bones belong to some of the early Bishops of Lindisfarne, brought with the monks when they fled the threat of Viking invasion in 875. Some of those bones will belong to Bishop Eadfrith who was the single scribe responsible for creating the Lindisfarne Gospels.

In the coffin Raine also found various objects from the 7th century that were either owned or used on St. Cuthbert. These included a portable altar, an ivory comb and the Pectoral Cross that has since become a symbol for the region. He removed the objects and put them on display in the Refectory library, along side some of the most important manuscripts in the Cathedral’s collection. They became the founding objects of the Cathedral’s first museum and the librarian’s salary was increased to £100 to compensate for their new role as a tour guide.

While these objects were all removed for further study and display, the remains of the deceased were returned to the grave. Like all other aspects of the operation, it was rushed and unsophisticated. The new coffin was closer to a packing crate than a coffin. Luckily the tomb would be opened again in 1899, providing a chance to give Cuthbert and the others a more fitting burial.

Feast Day – 20th March

Saint Cuthbert died on 20 March 687, as so Annual Feast day of Shrine of Saint Cuthbert in Durham Cathedral is on 20th March.

Mass Time

Weekdays

Wednesdays

Saturdays

Sundays

Church Visiting Time

Contact Info

Shrine of Saint Cuthbert in Durham Cathedral,

Durham DH1 3EH, England, United Kingdom

Phone No.

Tel : +44 191 386 4266

Accommodations

How to reach the Shrine

Newcastle International Airport in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, United Kingdom is the nearby Airport to the Shrine.

Durham Train Station in Durham, England, United Kingdom is the nearby Train Station to the Shrine.