Introduction

“Bethlehem, the city of David, is located about 5 miles south of the city of Jerusalem. According to tradition, Bethlehem is the place where David was born, and also where he was anointed king by the prophet Samuel.”

“The place which the supreme King of kings and the Lord of lords had chosen for entertaining his eternal and incarnate Son in this world was a most poor and insignificant hut or cave, to which most holy Mary and Joseph betook themselves after they had been denied all hospitality and the most ordinary kindness by their fellow-men.

This place was held in such contempt that though the town of Bethlehem was full of strangers in want of night-shelter, none would demean or degrade himself so far as to make use of it for a lodging; for there was none who deemed it suitable or desirable for such a purpose, except the Teachers of humility and poverty, Christ our Savior and his purest Mother.

On this account the wisdom of the eternal Father had reserved it for Them, consecrating it in all its bareness, loneliness and poverty as the first temple of light and as the house of the true Sun of justice, which was to arise for the upright of heart from the resplendent Aurora Mary, turning the night of sin into the daylight of grace.

History of Our Lady of Bethlehem

Most Holy Mary and saint Joseph entered the lodging thus provided for them and by the effulgence of the ten thousand angels of their guard they could easily ascertain its poverty and loneliness, which they esteemed as favors and welcomed with tears of consolation and joy.

When later the Magi approached, the heavenly mother awaited the pious and devout kings, standing with the Child in her arms. Amid the humble and poor surroundings of the cave, in incomparable modesty and beauty, she exhibited at the same time a majesty more than human, the light of heaven shining in her countenance. Still more visible was this light in the Child, shedding through the cavern effulgent splendor, which made it like a heaven.

The three kings of the East entered and at the first sight of the Son and Mother they were for a considerable space of time overwhelmed with wonder. They prostrated themselves upon the earth, and in this position they worshiped and adored the Infant, acknowledging Him as the true God and man, and as the Savior of the human race. By the divine power, which the sight of Him and his presence exerted in their souls, they were filled with new enlightenment. They perceived the multitude of angelic spirits, who as servants and ministers of the King of kings and Lord of lords attended upon Him in reverential fear.

Most Holy Mary, with saint Joseph and the sacred Child, took leave of the cave although with tenderest regret. When the Child and his mother took leave of the cave, God appointed an angel as its keeper and watcher, as He had done with the garden of Paradise. This guard had remained to this day, sword in hand at the opening of the cave; and never since then has an animal entered there.

Our Lady of Bethlehem

Our Lady of Bethlehem originates from the time spent in Bethlehem, the city of David, by the holy family. Bethlehem is located about 5 miles south of the city of Jerusalem. According to tradition, Bethlehem is the place where David was born, and also where he was anointed king by the prophet Samuel.

We do not know not long the Holy Family remained in Bethlehem, but, regardless, often in later years on their way from Nazareth to Jerusalem to pray in the Temple, they must have stopped off at Bethlehem. There, they might have visited the place of the Divine Birth and talked with the shepherds and those of the town who befriended them and were kind to them during the time of the Nativity.

How they must have stood, pondering on the events now past, as their gaze fell on the road which they had taken to Egypt to escape Herod’s wrath. The text, “And thou, Bethlehem, are not the least of the cities of Judah, for out of thee shall come the Savior who will deliver His people from their sins,” must have been frequently on their lips, as they in gratitude called down a blessing on the city of Bethlehem, for having given them the shelter it had on that glorious night of the Nativity, that “Silent Night, Holy Night.”

According to tradition, the Milk Grotto, not far from Bethlehem, is the site where the Holy Family took refuge during the Slaughter of the Innocents, before their flight to Egypt. While there, the Virgin Mary nursed her holy Child. Some drops of milk sprinkled the walls, changing to white the color of the stone. The site is venerated by both Christians and Muslims.

According to Franciscan, Brother Lawrence, an American who oversees the grotto and chapel for the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land, the grotto is at least 2,000 years old. Early Christians came to pray here, but the first structure was built around 385. Known in Arabic as “Magharet el Saiyidee” (The Grotto of Our Lady), the grotto, hollowed out of limestone, has become a place of pilgrimage for couples hoping to conceive a child.

A second legend identifies this site as the location where the Three Kings visited the Holy Family, and presented their gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh to the Divine Child. A tradition going back to the 7th century, located at this site the burial place of the innocent victims killed by Herod the Great after the birth of Jesus.

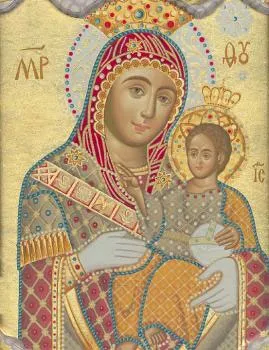

A Popular Painting of Mary with the Infant Jesus

A popular religious icon painting of Mary with the infant Jesus in her arms, the Virgin of Bethlehem (Virgen de Belén), is associated with Cuzco workshops of religious icon painters active between the 16th and 18th centuries. The Virgin wears a gold crown of precious stones, and a dark textile decorated with flowers covers her hair.

Her heavy, garnet-red vestment is embellished with golden accents and a long garland with numerous white dots that simulate pearls. The infant Jesus, whom she holds at her chest, is wrapped in a similarly patterned red and gold mantle and appears to emerge from her gown. One of the techniques used during the Cuzco Viceroyalty involved applying gold leaf on canvases and painted images to make them more beautiful. This technique is known as “estofado” and is used to imitate brocade or interwoven gold.

The artist of the Menil’s painting is not known, which is the case for many colonial paintings from Peru, but it can be securely attributed to one of the workshops active in Cuzco. It is one of several known examples in museum collections that depict the statue of the Virgin in the Parroquia Nuestra Señora Reina de Belén, or the Parish of Our Lady of Bethlehem in the city of Cuzco. The original statue, made during the 16th century, stands on the retablo behind the main altar of the parish. The sculpture is taken out of the church and processed and venerated during Catholic ceremonies and celebrations.

One of the most important is Corpus Christi or Holy Eucharist, which is celebrated in Cuzco during the month of June. The Virgin of Bethlehem is one of several types of Virgins and saints memorialized with a religious mass and festive celebrations with music and dance during Corpus Christi. Devotees process these statues on their shoulders through the streets of Cuzco for the people. In the painting, the Virgin stands on a round metal platform, which references the one used during festival processions to carry the statue.

While based on the sculpture, the Menil’s painting also closely resembles the representation of the Virgin in the late-17th-century painting The Virgin of Bethlehem with Bishop Gaspar de Mollinedo as Donor, which has been attributed by some scholars to the Quechua-Inca painter Basilio de Santa Cruz Pumacallao (1635–1710).

This monumental oil painting, which was part of the pictorial religious narrative in the Parroquia Nuestra Señora Reina de Belén, depicts Bishop Manuel de Mollinedo Angulo (1626–1699) petitioning the statue of the Virgin in the foreground. Mollinedo arrived in Cuzco after the major earthquake of 1650, which had severely damaged the church. He reportedly became a major patron of Santa Cruz Pumacallao’s work.

Cuzqueñous, people from Cuzco, consider the Virgin of Bethlehem to be the patroness of the city. Among Peruvians, she is often more endearingly referred to as Mamacha Belén or Mother Bethlehem. She is at the center of a cult of devotees, and her image is of great importance to the city’s religious life and culture. Popular accounts of miracles and divine intervention surround the Virgin of Bethlehem. The monumental painting attributed to Santa Cruz Pumacallao shows two of the best-known leyendas or stories.

In the upper-right corner of the painting is a scene narrating the origin of the Virgin of Bethlehem statue. According to the story, in the 16th century three fishermen from Bahía de Callao near Lima, Peru, came upon a floating wood crate. When they opened it, they discovered the wood statue of Virgin and a note that read: “Imagen de Nuestra Señora de Belén para la Ciudad de Cuzco” (Image of Our Lady of Bethlehem for the city of Cuzco). They carried the statue to Cuzco and presented it for placement in the Iglesia de los Reyes, which later changed its name to Parroquia Nuestra Señora Reina de Belén in honor of the Virgin.

Another common story, which is depicted in the upper-left corner of the painting, describes the salvation of a humble Cuzco man named Selengue, who had succumbed to vices and disbelief. During a procession of the Virgin, Selengue realized that she was about to tumble off her platform. He quickly intervened to prevent the accident and, through his strength, prevented the Virgin from toppling over. At that moment, an apparition of the Virgin interceded in a horrific vision Selengue had about his final judgement, saving him as a result of his pious action.

The Virgin of Bethlehem, like other Catholic imagery, was introduced after the Spanish conquest. Paintings and sculptures of religious figures served an educational purpose. Bishop Mollinedo and other influential figures came to Cuzco to spread their own religious and artistic values, such as those of the courtly life of Madrid. Spain had its own traditions and festivities related to many of the Virgins that we see in colonial painting from the Andes.

The Virgin’s garment is representative of 17th-century imperial fashion in Europe and symbolizes her divine status as Queen of Heaven and Mother of God as well as combining aspects of Inca textiles, jewelry, and weavings in bright colors. Despite the fact that European missionaries coerced the conversion of most, Andean people adapted and surreptitiously reinterpreted Catholic images in their own way.

They made them with local materials: dyes derived from plants and minerals, wood, gold, and silver. Quechua- and Aymara-speaking artists added colorful ornamentation indicative of royal Inca attire and festivities. They integrated Inca religious imagery and symbolism into the representations of Catholic saints: they acculturated Catholicism. This is visible in the extensive use of gold leaf in paintings and sculptures, which reflected the divine attributes of Inti, the god Sun.

Also, the way in which the virgin figures are shaped almost like mountains shows their association with Mother Earth or Pachamama, and the colorful, highly decorated dresses resemble costumes or capes utilized during indigenous dances and rituals as well as their European models. In the colonies, missionaries and officials allowed these adaptations as long as these images were accepted and incorporated into Andean peoples’ religious life.

The edges of the Menil’s painting have been cut, so part of the platform and the top of the Virgin’s crown are missing. The painting’s condition suggests years of devotional use during the colonial period and later. How large it was originally and the reasons why the painting was cropped are unclear. It is possible the trimming of the canvas occurred during a restoration. Some early Spanish colonial canvases were secured by glue directly to the frame or directly to the front of a stretcher or strainer. Failure of the adhesive could have damaged the edges, necessitating the cutting of portions of the painting.

Alternatively, changing the painting’s frame or support might have required cutting edge sections, which would have been difficult to do without damaging the margins of the canvas. It is also possible the painting was cropped while removing it from a sculpted framework in a church, a common fate for paintings included in such settings. Despite the alterations, this iconic image of the Virgin of Bethlehem with gilded embellishments exemplifies the hybrid nature and distinctive imagery of Andean Catholicism that define paintings from the Cuzco school.

Origin of the Tradition

According to tradition, the Milk Grotto, not far from Bethlehem, is the site where the Holy Family took refuge during the Massacre of the Innocents, before their flight to Egypt. While there, the Virgin Mary nursed her holy Child. Some drops of milk sprinkled the walls, changing to white the color of the stone. The site is venerated by both Christians and Muslims.

According to Franciscan, Brother Lawrence, an American who oversees the grotto and chapel for the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land, the grotto is at least 2,000 years old. Early Christians came to pray here, but the first structure was built around 385. Known in Arabic as “Magharet el Saiyidee” (The Grotto of Our Lady), the grotto, hollowed out of limestone, has become a place of pilgrimage for couples hoping to conceive a child.

A second legend identifies this site as the location where the Three Kings visited the Holy Family, and presented their gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh to the Divine Child. A tradition going back to the 7th century, located at this site the burial place of the innocent victims killed by Herod the Great after the birth of Jesus.

The Devotion to Our Lady of the Milk requests husbands and wives to pray together the third of the joyful mysteries of the rosary, meditating on the Nativity of the Lord.

There is also a Shrine of Our Lady of “La Leche y Buen Parto” (Spanish for “Our Lady of the Milk and Happy Delivery”) in St. Augustine, Florida.

The tradition of milk dates back to the first centuries of Christianity. Those converting to Christianity were given a mixture of milk and honey to drink, which in the early churches of Egypt, Rome, and North Africa was solemnly blessed at the Easter and Pentecost vigils. Milk with honey symbolized the union of the two natures in Christ. The custom of giving milk with honey to the newly baptized did not last long, but this tradition is visible in artistic representations.

Virgin Mary Painting

The image is painted on a wooden canvas. It measures 37.2 cm by 65 cm. The woman in the painting, the Virgin Mary, is medium-sized, and has some color on her face, lose hair, rays around the head, and eyes gazing upon the Child in swaddling clothes. She has one of her breasts uncovered, with small drops of milk falling towards the Child’s lips. He reclines in his mother’s arms, reciprocating the gaze of the mother. The Virgin Mary is wearing a blue blouse (not black), and a dark red or crimson mantle. Behind her, a dark grove of trees looks like a mountain.

The painting appeared next to a fountain, in the place where the future Dominican convent in San Juan would be founded, sometime between 1511 and 1522. According to tradition, during the English invasion of 1598, and Dutch invasion of 1625, the painting was hidden and later found. In 1714, a copy was placed in the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist (Cathedral of San Juan Bautista), in San Juan. During the Siege of Abercromby (1797), bishop Juan Bautista Zengotita gave orders for daily public prayer, to be held in parishes of the city.

According to Cayetano Coll y Toste’s legend, participants, mainly women, sang songs and litanies, and carried candles or torches in their hands. The painting of Our Lady of Bethlehem was carried through the city to ask God for help. According to this legend the invading army, frightened by such imposing sight, decided to withdraw and not attack the city. Today in the Caleta de San Juan, next to the ancient wall and facing the Bay of San Juan, there is a sculpture called “La Rogativa” or “The Public Petition,” which commemorates this chapter in the history of Puerto Rico.

Painter José Campeche attributed the protection of the city to Our Lady of Bethlehem. A painting meant to be a votive offering gives witness to the fact that inhabitants began to consider Our Lady as the “Protectora de la ciudad”, or “Guardian of the City.” He made many reproductions of the original Our Lady of Bethlehem, some of which are to be found in Old San Juan’s National Gallery and the Museum of the Universidad de Puerto Rico in Río Piedras.

Juan Alejo de Arizmendi, the first Puerto Rican bishop, spread devotion to the painting. In 1806 he granted forty days of indulgence to those who said a Hail Mary in front of the image, praying to God for Church intentions. He asked to place a copy in Santos Ángeles Custodios parish, in Yabucoa, and commended artist De La Espada to carve a wooden image that is located in the main altar of San Isidro Labrador’s parish, in Sabana Grande.

Towards 1864, priest Ven. Jerónimo Usera y Alarcón wrote a Noveen to Our Lady of Bethlehem. In the prologue he gave witness to the courage of the men and women who took part in the Siege of 1797, and called her Fellow Citizen of all Puerto Ricans.

The original Our Lady of Bethlehem disappeared from San José Church of Old San Juan (the old St. Thomas Church of the Dominicans) in 1972. A reproduction was made in Belgium and presented to the people of Puerto Rico on January 3, 2012. At the same date, the Angelical Confraternity of Our Lady of Bethlehem was restored.

Notable Representations

In the Catacombs of Priscilla, in Rome, a 2nd Century pictorial representation of the Virgin Mary may be found. Most likely it is a breastfeeding Virgin. There are other symbols referring to milk in the catacombs.

In the church of the Chilandari Monastery in Mount Athos, Greece, there is a “Virgin of Milk” in Byzantine style of the 11th and 12th centuries. It is called Panagia Galaktotrophusa.

During the 13th Century, in the town of Saydnaya, near Damascus, next to a wooden pictorial representation of the Virgin, there was an inscription in Latin: Hoc oleum ex ubere Genitris Dei Virginia Mariae emanavit in loco, qui Sardinia vocatur, ubi genitilitas est, ex imagine lignea, which means: “This oil flowed from the breast of the Virgin Mary, Mother of God, sculpted in wood. It took in a place gentiles call Sardinia.” It was moved from Constantinople to Saydnaya, probably in the 11th century.

Even after the 14th century, it still gave oil or milk. Templars distributed oil or milk among pilgrims in many countries. It is very likely that this famous shrine of Saydnaya, which was a pilgrimage place for Christians of the East and West, is the source (or one of the major sources) of this artistic theme.

Representations of the Virgin Mary in Flanders and the Netherlands

Responding to the devotion and worship of the Virgin in Europe during the Middle Ages, early Flemish painters produced numerous images of Mary. At the end of the 15th and 16th centuries, and up until the Council of Trent (1545–1563), the representations of the “Virgin of Milk” were popular in Flanders. Rogier Van der Weyden, presumed creator or inspirer of Puerto Rican “Lady of Bethlehem”, was a Flemish painter of fame and prestige in the 15th century. In 1435 he left his home town of Tournai to settle in Brussels, where he was appointed premier painter of the city. None of the paintings attributed to him are signed.

Attraction for his art was not limited to the region of Brussels. He received orders from distant regions such as Italy, Savoy, cities along the Rhine, and Spain. No historical data has been found that certify how this Flemish painting arrived in the New World. It is possible that Spanish Dominican friars coming to Puerto Rico took it along with them on their trip their first convent in Old San Juan. It is also possible that the first Spanish settlers (Juan Ponce de León with others), or even the first anonymous Franciscan friars who came to the New World, may have carried it on board.

Feast Day – 22nd January

Annual Feast Day of Our Lady of Bethlehem is held on 22nd January.