Introduction

Chartres Cathedral, also known as the Cathedral of Our Lady of Chartres (French: Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Chartres), is a Catholic church in Chartres, France, about 80 km (50 miles) southwest of Paris, and is the seat of the Bishop of Chartres. Mostly constructed between 1194 and 1220, it stands on the site of at least five cathedrals that have occupied the site since the Diocese of Chartres was formed as an episcopal see in the 4th century. It is one of the best-known and most influential examples of Classic Gothic Architecture, An actual version of Encyclopedia Britannica simply calls it Gothic. It stands on Romanesque basements, while its north spire is more recent (1507-1513) and is built in the more ornate Flamboyant style.

Long renowned as “one of the most beautiful and historically significant cathedrals in all of Europe,” it was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1979, which called it “the high point of French Gothic art” and a “masterpiece”.

The cathedral is well-preserved and well-restored: the majority of the original stained glass windows survive intact, while the architecture has seen only minor changes since the early 13th century. The building’s exterior is dominated by heavy flying buttresses which allowed the architects to increase the window size significantly, while the west end is dominated by two contrasting spires, first one 105 metres (349 feet) plain pyramid completed around 1160 and another 113 metres (377 feet) early 16th century Flamboyant spire on top of an older tower. Equally notable are the three great façades, each adorned with hundreds of sculpted figures illustrating key theological themes and narratives.

Since at least the 12th century the cathedral has been an important destination for travellers. It attracts large numbers of Christian pilgrims, many of whom come to venerate its famous relic, the Sancta Camisa, said to be the tunic worn by the Virgin Mary at Christ’s birth, as well as large numbers of secular tourists who come to admire the cathedral’s architecture and art. A venerated Black Madonna enshrined within was crowned by Pope Pius IX on 31 May 1855.

History - Earlier Cathedrals

At least five cathedrals have stood on this site, each replacing an earlier building damaged by war or fire. The first church dated from no later than the 4th century and was located at the base of a Gallo-Roman wall; this was put to the torch in 743 on the orders of the Duke of Aquitaine. The second church on the site was set on fire by Danish pirates in 858. This was then reconstructed and enlarged by Bishop Gislebert, but was itself destroyed by fire in 1020. A vestige of this church, now known as Saint Lubin Chapel, remains, underneath the apse of the present cathedral. It took its name from Lubinus, the mid-6th-century Bishop of Chartres. It is lower than the rest of the crypt and may have been the shrine of a local saint, prior to the church’s rededication to the Virgin Mary.

In 962 the church was damaged by another fire and was reconstructed yet again. A more serious fire broke out on 7 September 1020, after which Bishop Fulbert decided to build a new cathedral. He appealed to the royal houses of Europe, and received generous donations for the rebuilding, including a gift from Cnut the Great, King of Norway, Denmark and much of England. The new cathedral was constructed atop and around the remains of the 9th-century church. It consisted of an ambulatory around the earlier chapel, surrounded by three large chapels with Romanesque barrel vault and groin vault ceilings, which still exist.

On top of this structure he built the upper church, 108 meters long and 34 meters wide. The rebuilding proceeded in phases over the next century, culminating in 1145 in a display of public enthusiasm dubbed the “Cult of the Carts” – one of several such incidents recorded during the period. It was claimed that during this religious outburst, a crowd of more than a thousand penitents dragged carts filled with building supplies and provisions including stones, wood, grain, etc. to the site.

In 1134, another fire in the town damaged the façade and the bell tower of the cathedral. Construction had already begun on the north tower in the mid-1120s, which was capped with a wooden spire around 1142. The site for the south tower was occupied by the Hotel Dieu that was damaged in the fire. Excavations for that tower were begun straight away. As it rose the sculpture for the Royal Portal (most of which had been carved beforehand) was integrated with the walls of the south tower.

The square of the tower was changed to an octagon for the spire just after the Second Crusade. It was finished about 1165 and reached a height of 105 metres or 345 feet, one of the highest in Europe. There was a narthex between the towers and a chapel devoted to Saint Michael. Traces of the vaults and the shafts which supported them are still visible in the western two bays. The stained glass in the three lancet windows over the portals dates from some time before 1145. The Royal Portal on the west façade, between the towers, the primary entrance to the cathedral, was probably finished a year or so after 1140.

Fire and Reconstruction (1194 – 1260)

On the night of 10 June 1194, another major fire devastated the cathedral. Only the crypt, the towers, and the new façade survived. The cathedral was already known throughout Europe as a pilgrimage destination, due to the reputed relics of the Virgin Mary that it contained. A legate of the Pope happened to be in Chartres at the time of the fire, and spread the word. Funds were collected from royal and noble patrons across Europe, as well as small donations from ordinary people. Reconstruction began almost immediately. Some portions of the building had survived, including the two towers and the Royal Portal on the west end, and these were incorporated into the new cathedral.

The nave, aisles, and lower levels of the transepts of the new cathedral were probably completed first, then the choir and chapels of the apse; then the upper parts of the transept. By 1220 the roof was in place. The major portions of the new cathedral, with its stained glass and sculpture, were largely finished within just twenty-five years, extraordinarily rapid for the time. The cathedral was formally re-consecrated in October 1260, in the presence of King Louis IX of France, whose coat of arms can be seen painted on a boss at the entrance to the apse, although this was added in the 14th century.

Later Modifications (13th – 18th centuries) and the coronation of Henry IV of France

Relatively few changes were made after this time. An additional seven spires were proposed in the original plans, but these were never built. In 1326, a new two-storey chapel, dedicated to Saint Piatus of Tournai, displaying his relics, was added to the apse. The upper floor of this chapel was accessed by a staircase opening onto the ambulatory. (The chapel is normally closed to visitors, although it occasionally houses temporary exhibitions.) Another chapel was opened in 1417 by Louis, Count of Vendôme, who had been captured by the English at the Battle of Agincourt and fought alongside Joan of Arc at the siege of Orléans. It is located in the fifth bay of the south aisle and is dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Its highly ornate Flamboyant Gothic style contrasts with the earlier chapels.

In 1506, lightening destroyed the north spire, which was rebuilt in the ‘Flamboyant’ style from 1507 to 1513 by architect Jean Texier. When he finished this, he began constructing a new jubé or Rood screen that separated the ceremonial choir space from the nave, where the worshippers sat.

On 27 February 1594, King Henry IV of France was crowned in Chartres Cathedral, rather than the traditional Reims Cathedral, since both Paris and Reims were occupied at the time by the Catholic League. The ceremony took place in the choir of the church, after which the King and the Bishop mounted the rood screen to be seen by the crowd in the nave. After the ceremony and a mass, they moved to the residence of the bishop next to the cathedral for a banquet.

In 1753, further modifications were made to the interior to adapt it to new theological practices. The stone pillars were covered with stucco, and the tapestries which hung behind the stalls were replaced by marble reliefs. The rood screen that separated the liturgical choir from the nave was torn down and the present stalls were built. At the same time, some of the stained glass in the clerestory was removed and replaced with grisaille windows, greatly increasing the light on the high altar in the center of the church.

French Revolution and 19th Century

Early in the French Revolution a mob attacked and began to destroy the sculpture on the north porch, but was stopped by a larger crowd of townspeople. The local Revolutionary Committee decided to destroy the cathedral via explosives and asked a local architect to find the best place to set the explosions. He saved the building by pointing out that the vast amount of rubble from the demolished building would so clog the streets it would take years to clear away. The cathedral, like Notre Dame de Paris and other major cathedrals, became the property of the French State and worship was halted until the time of Napoleon, but it was not further damaged.

In 1836, due to the negligence of workmen, a fire began which destroyed the lead-covered wooden roof and the two belfries, but the building structure and the stained glass were untouched. The old roof was replaced by a copper-covered roof on an iron frame. At the time, the framework over the crossing had the largest span of any iron-framed construction in Europe.

2009 Restoration

In 2009, the Monuments Historiques division of the French Ministry of Culture began an $18.5-million program of works at the cathedral, cleaning the inside and outside, protecting the stained glass with a coating, and cleaning and painting the inside masonry creamy-white with trompe-l’œil marbling and gilded detailing, as it may have looked in the 13th century. This has been a subject of controversy.

Liturgy

The cathedral is the seat of the Bishop of Chartres of the Diocese of Chartres. The diocese is part of the ecclesiastical province of Tours. Every evening since the events of 11 September 2001, Vespers are sung by the Chemin Neuf Community.

The Towers and Clock

The two towers were built at different times, during the Gothic period, and have different heights and decoration. The north tower was begun in 1134, to replace a Romanesque tower that was damaged by fire. It was completed in 1150 and originally was just two stories high, with a lead-covered roof. The south tower was begun in about 1144 and was finished in 1150. It was more ambitious, and has an octagonal masonry spire on a square tower, and reaches a height of 105 meters. It was built without an interior wooden framework; the flat stone sides narrow progressively to the pinnacle, and heavy stone pyramids around the base give it additional support.

The two towers survived the devastating fire of 1194, which destroyed most of the cathedral except the west façade and crypt. As the cathedral was rebuilt, the famous west rose window was installed between the two towers (13th century), and in 1507, the architect Jean Texier (also sometimes known as Jehan de Beauce) designed a spire for the north tower, to give it a height and appearance closer to that of the south tower. This work was completed in 1513. The north tower is in a more decorative Flamboyant Gothic style, with pinnacles and buttresses. It reaches a height of 113 meters, just above the south tower. Plans were made for the addition of seven more spires around the cathedral, but these were abandoned.

At the base of the north tower is a small structure which contains a Renaissance-era twenty-four-hour clock with a polychrome face, constructed in 1520 by Jean Texier. The face of the clock is eighteen feet in diameter.

A fire in 1836 destroyed the roof and belfries of the cathedral, and melted the bells, but did not damage the structure below or the stained glass. The timber beams under the roof were replaced with an iron framework covered with copper plates.

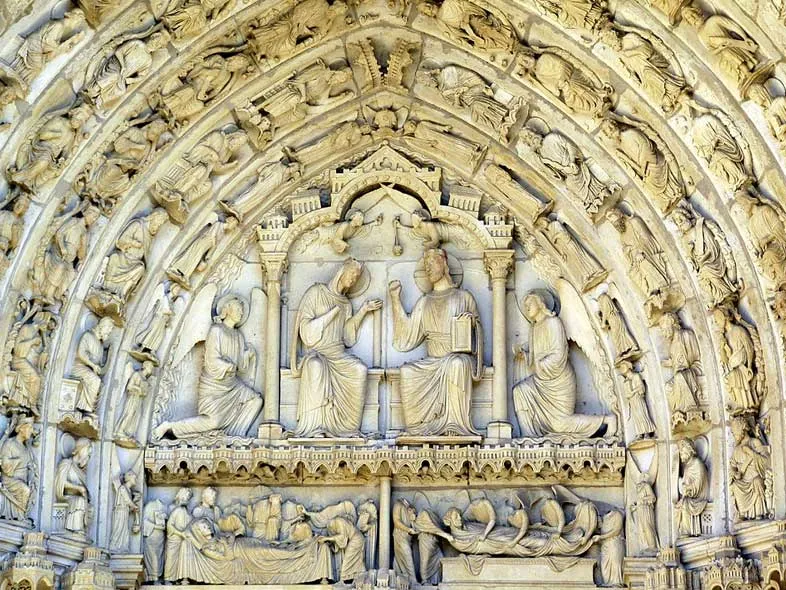

The Portals and Their Sculpture

The cathedral has three great portals or entrances, opening into the nave from the west and into the transepts from north and south. The portals are richly decorated with sculptures, which rendered biblical stories and theological ideas visible for both the educated clergy and layfolk who may not have had access to textual learning. Each of the three portals on the west façade focuses on a different aspect of Christ’s role in the world; on the right, his earthly Incarnation, on the left, his Ascension or his existence before his Incarnation, and in the center, his Second Coming, initiating the End of Time. The statuary of the Chartres portals is considered among the finest existing Gothic sculpture.

North Transept Portals (13th Century)

The statuary of the north transept portals is devoted to the Old Testament, and the events leading up to the birth of Christ, with particular emphasis on the Virgin Mary. The glorification of Mary in the center, the incarnation of her son on the left and Old Testament prefigurations and prophecies on the right. One major exception to this scheme is the presence of large statues of St Modesta (a local martyr) and St Potentian on the north west corner of the porch, close to a small doorway where pilgrims visiting the crypt (where their relics were stored) would once have emerged.

South Portal (13th Century)

The south portal, which was added later than the others, in the 13th century, is devoted to events after the Crucifixion of Christ, and particularly to the Christian martyrs. The decoration of the central bay concentrates on the Last Judgemnt and the Apostles; the left bay on the lives of martyrs; and the right bay is devoted to confessor saints. This arrangement is repeated in the stained glass windows of the apse.

The arches and columns of the porch are lavishly decorated with sculpture representing the labours of the months, the signs of the zodiac, and statues representing the virtues and vices. On top of the porch, between the gables, are pinnacles in the arcades with statues of eighteen Kings, beginning with King David, representing the lineage of Christ, and linking the Old Testament and the New.

Angels and Monsters

While most of the sculpture of the cathedral portrayed saints, apostles and other Biblical figures, such as the angel holding a sundial on the south façade, other sculpture at Chartres was designed to warn the faithful. These works include statues of assorted monsters and demons. Some of these figures, such as gargoyles, also had a practical function; these served as rain spouts to project water far away from the walls. Others, like the chimera and the strix, were designed to show the consequences of disregarding Biblical teachings.

Nave and Ambulatory

The nave, or main space for the congregation, was designed especially to receive pilgrims, who would often sleep in the church. The floor is slightly tilted so that it could be washed out with water each morning. The rooms on either side of Royal Portal still have traces of construction of the earlier Romanesque building. The nave itself was built after the fire, beginning in 1194. The floor of the nave also has a labyrinth in the pavement. The two rows of alternating octagonal and round pillars on either side of the nave receive part of the weight of the roof through the thin stone ribs descending from the vaults above. The rest of the weight is distributed by the vaults outwards to the walls, supported by flying buttresses.

The statue of Mary and the infant Christ, called Our Lady of the Pillar, replaces a 16th-century statue which was burned by the Revolutionaries in 1793.

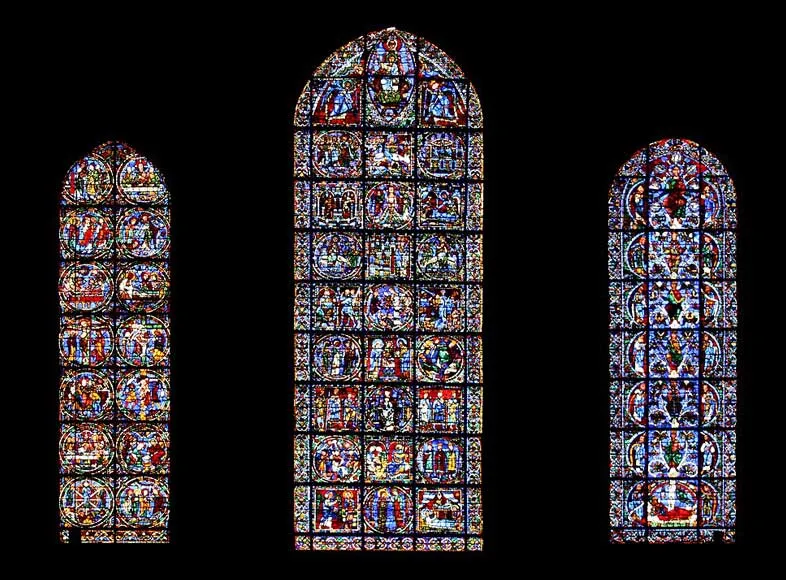

Stained Glass Windows

One of the most distinctive features of Chartres Cathedral is the stained glass, both for its quantity and quality. There are 167 windows, including rose windows, round oculi, and tall, pointed lancet windows. The architecture of the cathedral, with its innovative combination of rib vaults and flying buttresses, permitted the construction of much higher and thinner walls, particularly at the top clerestory level, allowing more and larger windows. Also, Chartres contains fewer plain or grisaille windows than later cathedrals, and more windows with densely stained glass panels, making the interior of Chartres darker but the colour of the light deeper and richer.

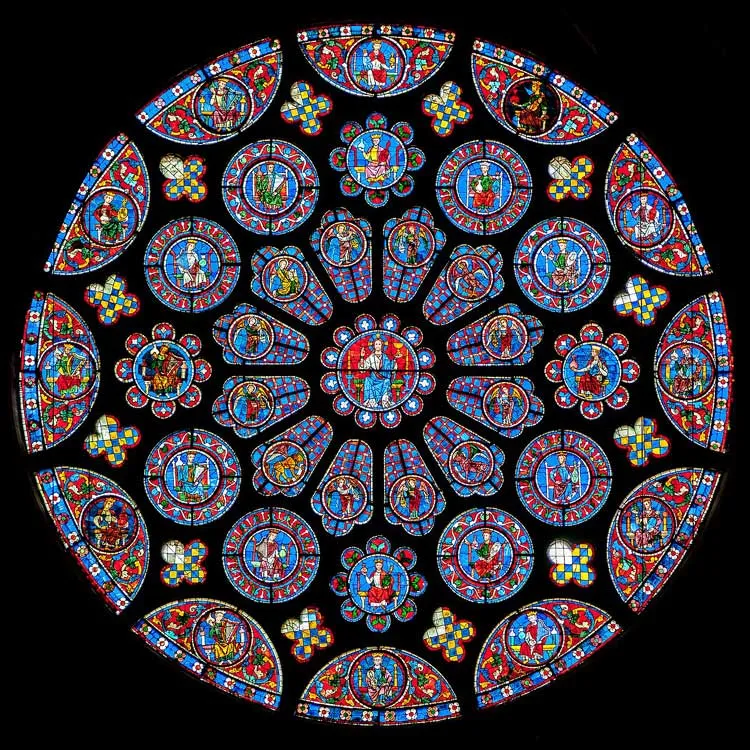

Rose Windows

The cathedral has three large rose windows. The western rose (12 m in diameter) shows the Last Judgment – a traditional theme for west façades. A central oculus showing Christ as the Judge is surrounded by an inner ring of twelve paired roundels containing angels and the Elders of the Apocalypse and an outer ring of 12 roundels showing the dead emerging from their tombs and the angels blowing trumpets to summon them to judgment.

The north transept rose (10.5 m diameter), like much of the sculpture in the north porch beneath it, is dedicated to the Virgin. The central oculus shows the Virgin and Child and is surrounded by twelve small petal-shaped windows, four with doves (the ‘Four Gifts of the Spirit’), the rest with adoring angels carrying candlesticks. Beyond this is a ring of twelve diamond-shaped openings containing the Old Testament Kings of Judah, another ring of smaller lozenges containing the arms of France and Castille, and finally a ring of semicircles containing Old Testament Prophets holding scrolls.

The presence of the arms of the French king (yellow fleurs-de-lis on a blue background) and of his mother, Blanche of Castile (yellow castles on a red background) are taken as a sign of royal patronage for this window. Beneath the rose itself are five tall lancet windows (7.5 m high) showing, in the center, the Virgin as an infant held by her mother, St Anne – the same subject as the trumeau in the portal beneath it. Flanking this lancet are four more containing Old Testament figures. Each of these standing figures is shown symbolically triumphing over an enemy depicted in the base of the lancet beneath them – David over Saul, Aaron over Pharaoh, St Anne over Synagoga, etc.

The south transept rose (10.5 m diameter) is dedicated to Christ, who is shown in the central oculus, right hand raised in benediction, surrounded by adoring angels. Two outer rings of twelve circles each contain the 24 Elders of the Apocalypse, crowned and carrying phials and musical instruments. The central lancet beneath the rose shows the Virgin carrying the infant Christ. Either side of this are four lancets showing the four evangelists sitting on the shoulders of four prophets – a rare literal illustration of the theological principle that the New Testament builds upon the Old Testament. This window was a donation of the Mauclerc family, the Counts of Dreux-Bretagne, who are depicted with their arms in the bases of the lancets.

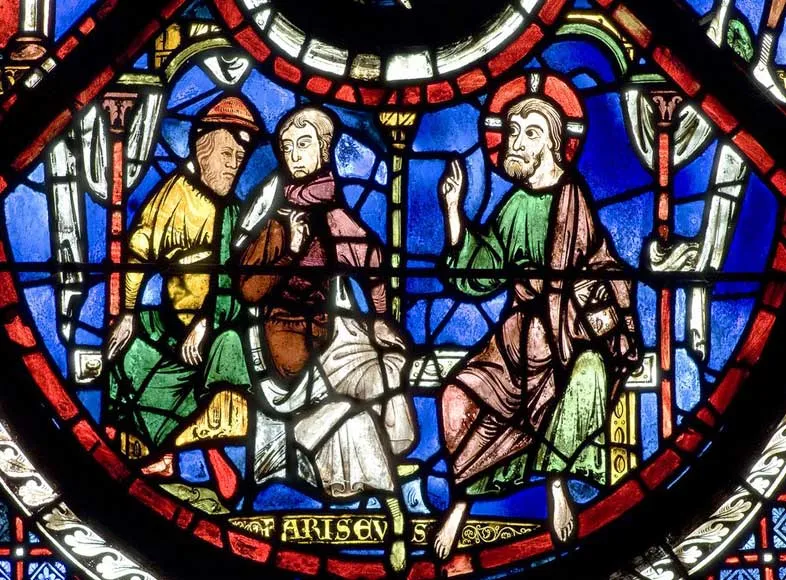

Windows in Aisles and the Choir Ambulatory

Each bay of the aisles and the choir ambulatory contains one large lancet window, most of them roughly 8.1m high by 2.2m wide. The subjects depicted in these windows, made between 1205 and 1235, include stories from the Old and New Testament and the Lives of the Saints as well as typological cycles and symbolic images such as the signs of the zodiac and labours of the months. One of the most famous examples is the Good Samaritan parable.

Several of the windows at Chartres include images of local tradesmen or labourers in the lowest two or three panels, often with details of their equipment and working methods. Traditionally it was claimed that these images represented the guilds of the donors who paid for the windows. In recent years however this view has largely been discounted, not least because each window would have cost around as much as a large mansion house to make – while most of the labourers depicted would have been subsistence workers with little or no disposable income.

Furthermore, although they became powerful and wealthy organisations in the later medieval period, none of these trade guilds had actually been founded when the glass was being made in the early 13th century. Another possible explanation is that the cathedral clergy wanted to emphasise the universal reach of the Church, particularly at a time when their relationship with the local community was often a troubled one.

Clerestory Windows

Because of their greater distance from the viewer, the windows in the clerestory generally adopt simpler, bolder designs. Most feature the standing figure of a saint or Apostle in the upper two-thirds, often with one or two simplified narrative scenes in the lower part, either to help identify the figure or else to remind the viewer of some key event in their life. Whereas the lower windows in the nave arcades and the ambulatory consist of one simple lancet per bay, the clerestory windows are each made up of a pair of lancets with a plate-traceried rose window above.

The nave and transept clerestory windows mainly depict saints and Old Testament prophets. Those in the choir depict the kings of France and Castile and members of the local nobility in the straight bays, while the windows in the apse hemicycle show those Old Testament prophets who foresaw the virgin birth, flanking scenes of the Annunciation, Visitation and Nativity in the axial window.

The Crypt (9th – 11th Century)

The small Saint Lubin Crypt, under the choir of the cathedral, was constructed in the 9th century and is the oldest part of the building. It is surrounded by a much larger crypt, the Saint Fulbert Crypt, which was completed in 1025, five years after the fire that destroyed most of the older cathedral. It is U-shaped and 230 meters long, next to the crypts of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome and Canterbury Cathedral. It is the largest crypt in Europe and serves as the foundation of the cathedral above.

The corridors and chapels of the crypt are covered with Romanesque barrel vaults, groin vaults where two barrel vaults meet at right angles, and a few more modern Gothic rib-vaults.

One notable feature of the crypt is the Well of the Saints-Forts. The well is thirty-three metres deep and is probably of Celtic origin. According to legend, Quirinus, the Roman magistrate of the Gallo-Roman town, had the early Christian martyrs thrown down the well. A statue of one of the martyrs, Modeste, is featured among the sculpture on the North Portico.

Another notable feature is the Our Lady of the Crypt Chapel. A reliquary here contains a fragment of the reputed veil of the Virgin Mary, which was donated to the cathedral in 876 by Charles the Bald, the grandson of Charlemagne. The silk veil was divided into pieces during the French Revolution. The largest piece is shown in one of the ambulatory chapels above. and the small Shrine of Our Lady of the Crypt.

The altar of the chapel is carved from a single block of limestone from the Berchères quarry, the source of most of the stone of the cathedral. The fresco on the wall dates from about 1200 and depicts the Virgin Mary on her throne. The Three Kings are to her left, and the Apostles Savinien and Potentien to her right. The chapel also has a modern stained glass window, the Mary, Door to Heaven Window, made by Henri Guérin, made by cementing together thick slabs of stained glass.

High Altar (18th Century)

The high ornamental stone screen that separates the choir from the ambulatory was put in place between the 16th and 18th century, to adapt the church to a change in liturgy. It was built in the late Flamboyant Gothic and then the Renaissance style. The screen has forty niches along the ambulatory filled with statues by prominent sculptors telling the life of Christ. The last statues were put in place in 1714.

Grand Organ

The buffet, or wooden case of the grand organ of the cathedral is among the oldest in France. It was first built in the 14th century, rebuilt in 1475, and enlarged in 1542. Both the organ and the tribune have been classified as separate historic monuments since 1840.

The organ is placed in the nave at the crossing of the south transept, sixteen meters above the floor of the nave, in close proximity to the choir, to assure the best sound quality throughout the cathedral. The whole case is fifteen meters high, with the top of its central tower thirty meters above the floor of the nave. The case was rebuilt during the Renaissance, and largely took its present form. Closer study of the case by the Ministry of Culture showed that the early case was covered with polychrome painting; yellow ochre under a varnish of reddish brown in earlier layer, and later by a brighter yellow on white. This study also showed that the mechanism was in very poor condition, and urgently needed reconstruction.

A major rebuilding and enlargement of the organ instrument took place in 1969–71, both to restore the ageing mechanism, and to add new keys and functions. The case was also restored, with the cost paid entirely by the French State, as was part of the cost of restoring the organ itself. As a result of this, and after further work on the organ in 1996, the instrument has 70 stops, totaling of over 4000 pipes.

Labyrinth

The labyrinth (early 1200s) is a famous feature of the cathedral, located on the floor in the center of the nave. Labyrinths were found in almost all Gothic cathedrals, though most were later removed since they distracted from the religious services in the nave. They symbolized the long winding path towards salvation. Unlike mazes, there was only a single path that could be followed.

On certain days the chairs of the nave are removed so that visiting pilgrims can follow the labyrinth. Copies of the Chartres labyrinth are found at other churches and cathedrals, including Grace Cathedral, San Francisco. Artist Kent Bellows depicts a direct reference to the labyrinth, which he renders in the background of at least one of his artworks; Mandala, 1990.

Chartres en lumières

Elected in 2001, the new municipal team of Chartres tackled the renovation of the historic heritage of its city center, which it considered to be one of its priority objectives. Several redevelopment projects have been undertaken, stretching from the cathedral to the old medieval gates of the city. In order to highlight this renovated city center, the City of Chartres has chosen to develop events around light. These events aim to bring together the inhabitants and to invite tourists to discover the heritage of Chartres in an unusual way.

In 2003, the City of Chartres created its Festival of Light: on the night of the third Saturday in September (the European Heritage Days weekend), it illuminated certain elements of its heritage in the heart of the city. Given the success of this event, the city decided to make it permanent: in 2004, Chartres en lumières was born! Since then, the city center has been illuminated through its monuments.

To ensure that visitors are amazed, new illuminations are proposed every year and new historical sites are regularly added to the program! And since 2020, the season extends to the end of the year and includes several Christmas-themed illuminations. A great way to perpetuate the magic of this time of year (and to start the next one off right)!

Highlights and Animations to mark the Season

In addition to the scenographies, the season of Chartres en lumières is interspersed with highlights such as the Festival of Light and the Trail In Chartres en lumières, guided tours of the event are also organized by our partners and can take original forms. And the little train of Chartres does not fail to offer visitors a commented tour of Chartres in lights, comfortably installed.

Feast Day – 13th July

Annual Feast Day of Our Lady of Chartres celebrated on 13th July.

It is actually pre-Christian, like the Athenians’ “altar to the unknown god” and was dedicated to the Virgin who would bring forth a son, at least a century before the birth of Christ.

Mass Time

Weekdays

- 11:45 am

- 6:15 pm

- 7:00 pm

Tuesdays

- 9:00 am

- 11:45 am

- 6:15 pm

- 7:00 pm

Fridays

- 7:00 am

- 9:00 am

- 11:45 am

- 6:15 pm

- 7:00 pm

Saturdays

- 11:45 am

- 6:00 pm

Sundays

- 9:00 am

- 11:00 am

- 6:00 pm

- 6:30 pm

Church Visiting Time

Contact Info

16, Cloître Notre Dame,

28000, Chartres, France.

Phone No.

Tel : +33 2 37 21 59 08

Accommodations

How to reach the Cathedral

Paris-Orly International Airport in Orly, France is the nearby Airport to the Cathedral.

Gare de Chartres Train Station in Chartres, France is the nearby Train Station to the Cathedral.