Introduction

Aachen Cathedral (German: Aachener Dom) is a Roman Catholic church in Aachen, Germany and the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Aachen. One of the oldest cathedrals in Europe, it was constructed by order of Emperor Charlemagne, who was buried there in 814. From 936 to 1531, the Palatine Chapel saw the coronation of thirty-one German kings and twelve queens.

The church has been the mother church of the Diocese of Aachen since 1930. In 1978, Aachen Cathedral was one of the first 12 items to be listed on the UNESCO list of World Heritage sites, because of its exceptional artistry, architecture, and central importance in the history of the Holy Roman Empire.

Charlemagne began the construction of the Palatine Chapel around 796, along with the rest of the palace structures. The construction is credited to Odo of Metz. The exact date of completion is unclear; however, a letter from Alcuin, in 798, states that it was nearing completion, and in 805, Pope Leo III consecrated the finished chapel. A foundry was brought to Aachen near the end of the 8th century and was utilized to cast multiple bronze pieces, from doors and the railings, to the horse and bear statues. Charlemagne was buried in the chapel in 814. It suffered a large amount of damage in a Viking raid in 881, and was restored in 983.

Following Charlemagne’s canonization by Antipope Paschal III in 1165, the chapel became a draw for pilgrims. Due to the enormous flow of pilgrims, in 1355 a Gothic choir hall was added, and a two-part Capella vitrea (glass chapel) which was consecrated on the 600th anniversary of Charlemagne’s death. A cupola, several other chapels, and a steeple were also constructed at later dates. It was restored again in 1881, when the Baroque stucco was removed.

History of Aachen Cathedral, Germany

The cathedral uses two distinct architectural styles, with small portions of a third. First, the core of the cathedral is the Carolingian-Romanesque Palatine Chapel, which was modeled after San Vitale at Ravenna and is notably small in comparison to the later additions. Secondly, the choir was constructed in the Gothic style. Finally, there are portions that show Ottonian style, such as the area around the throne.

The octagon in the centre of the cathedral was erected as the chapel of the Palace of Aachen between 796 and 805 on the model of other contemporary Byzantine buildings. The architect was Odo of Metz, and the original design was of a domed octagonal inner room enveloped by a 16 sided outer wall. The span and height of Charlemagne’s Palatine chapel was unsurpassed north of the Alps for over two hundred years.

The Palatine chapel consisted of a high octagonal room with a two-story circuit below. The inner octagon, with a diameter of 14.46 metres (47.4 ft), is made up of strong piers, on which an octagonal cloister vault lies, covering the central room. Around this inner octagon is a sixteen sided circuit of low groin vaults, supporting a high gallery above. This upper story was known as the Hochmünster (high church). The arched openings of the lower story are only about half as high as those of the Hochmünster, as a result of which the lower story looks stocky and bulky.

The two floors are separated from each other by an expansive cornice. The high altar and Imperial throne are located on the upper circuit of the Palatine chapel in an octagonal side room, covered by a barrel vault lying on an angle. This area was connected with the palace by a passage. Above the arches of the gallery, an octagonal drum with window openings rises, on top of which is the cupola.

On the east end was a small apse that protruded and was, in later years, replaced by the choir. Opposite of this, was the tiered entrance to the rest of the now defunct palace, West work. Light is brought in by a three tiered system of circular arched windows. The corners of the octagonal dome are joined with the walls with a system of paired pilasters with Corinthian capitals.

Architecture

The upper gallery openings are divided by a grid of columns. These columns are ancient and come from St. Gereon in Cologne. Charlemagne allowed further spolia to be brought to Aachen from Rome and Ravenna at the end of the 8th century. In 1794, during the French occupation of the Rheinland, they were removed to Paris, but in 1815 up to half the pieces remaining in the Louvre were brought back to Aachen. In the 1840s they were restored to their original places once more and new columns of Odenberg granite were substituted for the missing columns. The interior walls were initially lined with a marble facade.

The round arched openings in the upper floor in the side walls of the octagon, between the columns, in front of a mezzanine, are decorated with a metre-high railing of Carolingian bronze rails. These bronze rails were cast 1200 years ago in a single piece according to Roman models.

The original cupola mosaic was probably executed around 800 and known from Medieval sources depicted Christ as the triumphant lord of the world, surrounded by the symbols of the Four Evangelists, with the twenty-four elders from the Apocalypse of John offering their crowns to him. In 1880-81 it was recreated by the Venetian workshop of Antonio Salviati, according to the plans of the Belgian architect Jean-Baptiste de Béthune. The dome was intricately decorated with a mosaic tile.

The exterior walls of the Carolingian octagon, made of quarry stone, are largely unjointed and lack further ornamentation. The only exception is that the projections of the pillars of the cupola are crowned by antique capitals. Above the Carolingian masonry, there is a Romanesque series of arches above a late Roman gable. The Octagon is crowned by unusual baroque vents.

Aachen Cathedral was plastered red in the time of Charlemagne, according to the most recent findings of the Rheinish Office for Monuments. This plaster was made longer-lasting through the addition of crushed red brick. The colour was probably also a reference to the imperial associations of the work.

Geometry

The question of which geometric concepts and basic dimensions lie at the basis of the chapel’s construction is not entirely clear even today. Works of earlier cathedral architects mostly followed either the Drusian foot (334 mm) or the Roman foot (295.7 mm). However, these measurements require complex theories to explain the church’s actual dimensions.

In 2012, the architectural historian Ulrike Heckner proposed a theory of a new, hitherto unknown unit of measure of 322.4 mm, the so-called Carolingian foot, to which all other measurements in the Palatine chapel can be traced back. This measurement is referred to as the Aachener Königsfuß (Aachen royal foot), after the similarly sized Parisian royal foot (324.8 mm).

Beyond this, there is a symbolic layer to the octagon. Eight was a symbol of the eighth day (Sunday as the sabbath) and therefore symbolised the Resurrection of Jesus Christ and the promise of eternal life. Likewise, ten, the number of perfection in Medieval architectural symbolism, is frequent in the Palatine Chapel: Its diameter (including the circuit surrounding the dome) measures a hundred Carolingian feet – equivalent to the height of the dome.

West Work

The west work (western facade) of the cathedral is of Carolingian origin, flanked by two stair-towers. It is a two-story building, completed by a porch from the 18th century at the west end. The bronze leaves attached to this porch, the Wolfstür (Wolf’s Door), weigh 43 hundredweight altogether. The main entrance to the cathedral, the door was cast in Aachen around 800 and was located between the west work and the octagon in the so-called hexadecagon up to 1788. The portal was restored in 1924.

Each leaf is divided into eight rectangles – a number which had religious symbolism in Christianity, as a symbol of Sunday, the day of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ and also of perfection (as did twelve, also) and can be found in the measurements of the Palatine Chapel over and over again. These boxes were framed by decorative strips, which are made of egg-shaped decorations.

The egg was considered a symbol of life and fertility from antiquity. In Christian belief it was imbued with the even wider symbolism of Eternal Life. The door-rings in the shape of lions’ heads are wreathed by 24 acanthus scrolls – again to be understood at the deepest level through numerology. The Wolfstür’s imitation of the shape of the ancient Roman temple door signifies Charlemagne’s claim, to have established a New Rome in Aachen with the Palatine Chapel as the distinctive monumental building.

Sculptures

There were multiple sculptures, made of bronze, including an equestrian piece probably meant as a parallel of a statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome. In the fore hall, there is a bronze sculpture of a bear, which was probably made in the 10th century, in Ottonian times. Opposite it is a bronze pine cone with 129 perforated scales, which stands 91 cm high; its date is controversial and ranges from the 3rd to the 10th century.

Its base is clearly Ottonian and includes an inscription written in Leonine hexameter, which refers to the Tigris and Euphrates rivers of Mesopotamia. According to one view, the pine cone would originally have served as a waterspout on a fountain and would have been placed in the atrium of the Palatine chapel in Carolingian times.

The upper level is characterised by an exceptionally fine brick western wall. Inside, it bulges outward, while the outside bulges inwards, so that the Carolingian west wall can be seen as a convex-concave bulge. Before the construction of the porch in the 18th century, the Carolingian west facade, when seen from the Narthex, was particularly evocative: a large niche, topped by a semi-circular arch in the western upper level corresponded to the semicircle of the barrel vault of the lower level.

Today, the western wall is broken up by the large western window. The large window frame dates from the Gothic period and replaced a smaller window from Carolingian times, which was probably structured as a mullion (a double arch with a column in the centre). The modern window was designed by Ewald Mataré in 1956. Mataré’s design imitates, however abstractly, the structure of the Carolingian bronze gate inside the dome. Bronze and unprocessed quartz form the window itself.

The function of the upstairs part of the west facade is not entirely clear. The right of baptism (long reserved for the Collegiate Church of Mary) was at a baptismal font, which was behind the marble throne, until the end of the Ancien Régime. Possibly the space was involved in these ceremonies. Furthermore, in the western wall, under the great west window, there is a Fensetella (small window) even today, through which there is line of sight to the court below, the former atrium. It is certain that the so-called Carolingian Passage entered this room on its northern wall, connecting the Aula Regia (King’s Hall) in the north of the palace with the church.

The lower, barrel-vaulted room in the west probably served as Charlemagne’s sepulchre after his death on 28 January 814 and his burial in the Persephone sarcophagus. The floors of the western facade lying above this room were remodelled in the first half of the 14th century and in the 17th century; the tower was completed between 1879 and 1884.

Choir

Between 1355 and 1414, on the initiative of the Marienstift and the mayor of Aachen Gerhard Chorus (1285–1367), a Gothic Choir was built to the east of the Octagon. Before this there must have been a rectangular Carolingian choir.

The Gothic choir measures 25m in length, 13m wide and 32m high. Its external wall is broken, as much as possible, by windows – the surface area of the glass is more than 1,000m² and led to the name Glashaus (glass house). This was conceived as a glass reliquary for the holy relics of Aachen and for the body of Charlemagne.

The design is arranged on the model of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, likewise a space for important relics and a royal palace chapel. For protection of the vault of the choir, iron rods were built in at the time of construction, to counter the lateral force on the narrow stone supports and to allow as much space as possible between them for window space.

Treasury

The Aachen Cathedral Treasury contains one of Europe’s most significant church treasuries, a unique collection of precious objects from the history of the Aachen Cathedral. After a redesign of the Treasury’s installation in order to sufficiently address modern conservational, technical, and safeguarding requirements, the Cathedral Treasury was opened in the winter of 1995. Today more than a 100 cultural treasures are displayed on different levels on more than 600 square meters of exhibition area.

The Cathedral Treasury features sacred cultural treasures from Late Antiquity, as well as the Carolingian, Ottonian, Hohenstaufen and Gothic eras. Its lofty position is mostly owed to the fact that for centuries – from 936 until 1531 – today’s Aachen Cathedral was the coronation church for the Roman-German kings. Some of the acquired pieces can be traced back to royal donations, others show the European importance of the church dedicated to the Virgin Mary, today’s Aachen Cathedral as a pilgrimage church and as the burial church of Charlemagne.

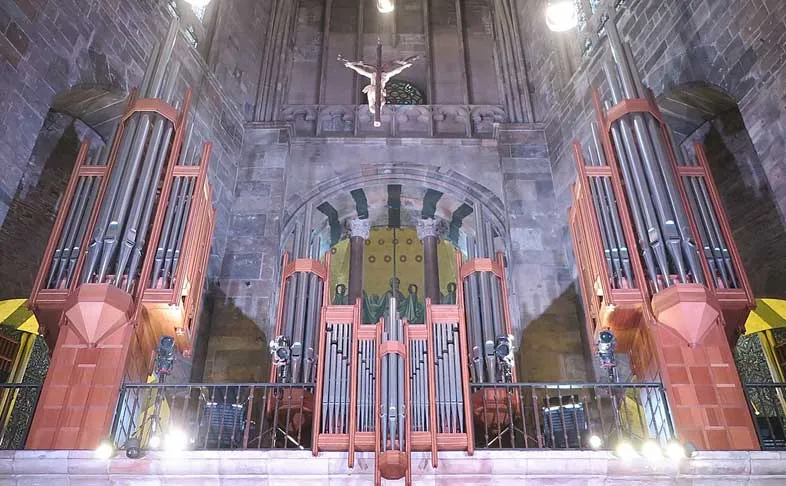

Organs

The organ system of Aachen Cathedral was installed in 1939. It consists in part of the earlier organ, installed 1845–1847, which was built by the organ builder Wilhelm Korfmacher of Linnich. This Korfmacher organ had 60 stops, distributed in three works.

The current instrument was installed in 1939 by Johannes Klais (Bonn) and expanded to 65 stops, which were distributed thereafter in five works. To achieve a balanced sound throughout the cathedral, the parts were distributed through the cathedral: in the northwest and southwest niches of the choir are the works of the High organ, while a swallow’s nest organ was hung on the east pillar of the octagon.

In 1991–1993, the organ was restored by the Klais organ company and increased to a total of 89 stops. At this time the swallow’s nest organ was turned into a new, independent instrument, which now stands in the upper church, between the octagon and the choir.

As well as a chamber organ, the cathedral also has a small organ, called the Zoboli Organ. This was built by the north Italian organ builder, Cesare Zomboli, probably sometime around 1850. The pipe works, wind box, and keyboard survive. The historic housing no longer exists, but the current housing was built later on the model of a north Italian cabinet organ in classicist style. The instrument is arranged in the classic Italian style, with the typical stops of the Roman style as well.

Bells

In the belfry of the tower, eight bells hang on wooden yokes in a wooden bell frame. The bells were cast three years after the city fire of 1656 by Franz Von Trier and his son Jakob. This disposition, altered from that of medieval times, has been maintained to this day, except that the Mary bell has had to be replaced twice. The modern Mary bell was made in 1958 and was cast by Petit & Gebr. Edelbrock.

Palatine Chapel – Throne of Charlemagne

The Palatine Chapel in Aachen is an early medieval chapel and remaining component of Charlemagne’s Palace of Aachen in what is now Germany. Although the palace itself no longer exists, the chapel was preserved and now forms the central part of Aachen Cathedral. It is Aachen’s major landmark and a central monument of the Carolingian Renaissance. The chapel held the remains of Charlemagne. Later it was appropriated by the Ottonians and coronations were held there from 936 to 1531. As part of Aachen Cathedral, the chapel is designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Charlemagne, the first Holy Roman Emperor, began building his Palatine Chapel (palace chapel) in 786 AD. The Palatine Chapel has been described as a “masterpiece of Carolingian architecture”. It is all that remains today of Charlemagne’s extensive palace complex in Aachen.

The Palatine Chapel was designed by Odo of Metz. He based it on the Byzantine church of San Vitale (completed 547 AD) in Ravenna, Italy. This accounts for the very eastern feel to the chapel, with its octagonal shape, striped arches, marble floor, golden mosaics, and ambulatory. It was consecrated in 805 to serve as the imperial church.

The Shrine of Charlemagne

The Shrine contains the mortal remains of Charlemagne, canonized in 1165, since its completion in 1215. Scenes from the life of Charlemagne by Pseudo-Turpin are displayed upon the roof reliefs, the long axes are each occupied by eight emperors and kings.

Pala d’oro

A golden altarpiece, the Pala d’Oro which today forms the Antependium of the high altar was probably created around 1020 in Fulda. It consists of seventeen individual gold panels with reliefs in repoussé. In the centre, Christ is enthroned as Redeemer in a Mandorla, flanked by Mary and the Archangel Michael. Four round medallions with images of the Evangelists’ symbols show the connection to the other twelve relief panels with depictions from the life of Jesus Christ. They begin with the entry into Jerusalem and end with the encounter of the women with the risen Christ in front of the open grave on Easter morning. The depictions are read from left to right, like a book.

Stylistically, the Pala d’Oro is not uniform. The first five reliefs probably come from a goldsmith taught in the Rheinland and is distinguished by a strikingly joyful narration. It probably derives from a donation of Emperor Otto III. The other panels, together with the central group of Christ, Mary, and Michael, draws from Byzantine and late Carolingian predecessors and was likely first added under Otto’s successor, Henry II, who also donated the Ambo of Henry II.

Presumably, in the late 15th century, the golden altarpiece formed a massive altar system together with the twelve reliefs of apostles in the cathedral treasury, along with altarpieces with scenes from the life of Mary, which would have been dismantled in 1794 as the French Revolutionary troops approached Aachen.

Barbarossa Chandelier

The chandelier was donated by Emperor Frederick I and his wife Beatrix and is attached to an ironwork chain of 27 meters. Its octagonal shape was meant to dovetail harmonically and symbolically with the overall structure of the church. Imagery and inscription refer to the Heavenly Jerusalem.

The Cupola Mosaic

The cupola mosaic displays the adoration of the 24 eldest as written in the book of Revelation, who, at the end of times, offer their crowns to the Lord with covered hands. The recent mosaic dates from the end of the 19th century and cites an engraving by Ciampini from 1699.

Feast Day – 15th August

The Patron Saint’s Festival is celebrated on August 15th on the Assumption of the Virgin Mary.

January 28th is the feast of Blessed Charlemagne: King of the Franks and the Lombards, Emperor of the Romans, and “Father of Europe”, who died on this day in 814. January 28th is the Feast of Saint Charlemagne who was buried in Aachen Cathedral in 814.

Mass Time

Weekdays

Saturdays

Sundays

Church Visiting Time

Contact Info

Domhof, 1, 52062,

Aachen, Germany.

Phone No.

Tel : +49 241 477090

Accommodations

How to reach the Cathedral

Maastricht Aachen Airport in Limburg, Netherlands is located 5 NM northeast of Maastricht and 15 NM northwest of Aachen, Germany is the nearby Airport to the Cathedral. Cologne Bonn Airport is the international airport in Köln, Germany is the nearby Airport to the Cathedral in Germany.

Aachen, Schanz Bf Train Station in Aachen, Germany is the nearby Train Station to the Cathedral.