Introduction

The Basilica of Saint Mary Major (Italian: Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, Latin: Basilica Sanctae Mariae Maioris), or church of Santa Maria Maggiore, is a Major papal basilica as well as one of the Seven Pilgrim Churches of Rome and the largest Catholic Marian church in Rome, Italy.

The basilica enshrines the venerated image of Salus Populi Romani, depicting the Blessed Virgin Mary as the health and protectress of the Roman people, which was granted a Canonical coronation by Pope Gregory XVI on 15 August 1838 accompanied by his Papal bull Cælestis Regina.

Pursuant to the Lateran Treaty of 1929 between the Holy See and Italy, the Basilica is within Italian territory and not the territory of the Vatican City State. However, the Holy See fully owns the Basilica, and Italy is legally obligated to recognize its full ownership thereof and to concede to it “the immunity granted by International Law to the headquarters of the diplomatic agents of foreign States.” In other words, the complex of buildings has a status somewhat similar to a foreign embassy.

History of Basilica of Saint Mary Major, Rome

The Basilica is sometimes referred to as Our Lady of the Snows, a name given to it in the Roman Missal from 1568 to 1969 in connection with the liturgical feast of the anniversary of its dedication on 5 August, a feast that was then denominated Dedicatio Sanctae Mariae ad Nives (Dedication of Saint Mary of the Snows). This name for the basilica had become popular in the 14th century in connection with a legend that circa the year 352, during “the pontificate of Liberius, a Roman patrician John and his wife, who were without heirs, made a vow to donate their possessions to the Virgin Mary.

They prayed that she might make known to them how they were to dispose of their property in her honour. On 5 August, at the height of the Roman summer, snow fell during the night on the summit of the Esquiline Hill. In obedience to a vision of the Virgin Mary which they had the same night, the couple built a basilica in honour of Mary on the very spot which was covered with snow.

The legend is first reported only after AD 1000. It may be implied in what the Liber Pontificalis, of the early 13th century, says of Pope Liberius: “He built the basilica of his own name (i.e. the Liberian Basilica) near the Macellum of Livia”. Its prevalence in the 15th century is shown in the painting of the Miracle of the Snow by Masolino da Panicale.

The feast was originally called Dedicatio Sanctae Mariae (Dedication of Saint Mary’s), and was celebrated only in Rome until inserted for the first time into the General Roman Calendar, with ad Nives added to its name, in 1568. A congregation appointed by Pope Benedict XIV in 1741 proposed that the reading of the legend be struck from the Office and that the feast be given its original name. No action was taken on the proposal until 1969, when the reading of the legend was removed and the feast was called In dedicatione Basilicae S. Mariae (Dedication of the Basilica of Saint Mary). The legend is still commemorated by dropping white rose petals from the dome during the celebration of the Mass and Second Vespers of the feast.

The earliest building on the site was the Liberian Basilica or Santa Maria Liberiana, after Pope Liberius (352–366). This name may have originated from the same legend, which recounts that, like John and his wife, Pope Liberius was told in a dream of the forthcoming summer snowfall, went in procession to where it did occur and there marked out the area on which the church was to be built. Liberiana is still included in some versions of the basilica’s formal name, and “Liberian Basilica” may be used as a contemporary as well as historical name.

On the other hand, the name “Liberian Basilica” may be independent of the legend, since, according to Pius Parsch, Pope Liberius transformed a palace of the Sicinini family into a church, which was for that reason called the Sicinini Basilica. This building was then replaced under Pope Sixtus III (432–440) by the present structure dedicated to Mary. However, some sources say that the adaptation as a church of a pre-existing building on the site of the present basilica was done in the 420s under Pope Celestine I, the immediate predecessor of Sixtus III.

Long before the earliest traces of the story of the miraculous snow, the church now known as Saint Mary Major was called Saint Mary of the Crib (Sancta Maria ad Praesepe), a name it was given because of its relic of the crib or manger of the Nativity of Jesus Christ, four boards of sycamore wood believed to have been brought to the church, together with a fifth, in the time of Pope Theodore I (640–649). This name appears in the Tridentine editions of the Roman Missal as the place for the pope’s Mass (the station Mass) on Christmas Night, while the name “Mary Major” appears for the church of the station Mass on Christmas Day.

Status as A Papal Major Basilica

No Catholic church can be honoured with the title of basilica unless by apostolic grant or from immemorial custom. St. Mary Major is one of the only four that hold the title of major basilica. The other three are the basilicas of St. John in the Lateran, St. Peter, and St. Paul outside the Walls. (The title of major basilica was once used more widely, being attached, for instance, to the Basilica of St. Mary of the Angels in Assisi).

Along with all of the other major basilicas, St. Mary Major is also styled a papal basilica. Before 2006, the four papal major basilicas, together with the Basilica of St. Lawrence outside the Walls were referred to as the patriarchal basilicas of Rome, and were associated with the five ancient patriarchates (see Pentarchy). St. Mary Major was associated with the Patriarchate of Antioch.

The five papal basilicas along with the Basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem and San Sebastiano fuori le mura were the traditional Seven Pilgrim Churches of Rome, which were visited by pilgrims during their pilgrimage to Rome following a 20-kilometre (12 miles) itinerary established by St. Philip Neri on 25 February 1552.

History of the Present Church

It is now agreed that the present church was built under Pope Celestine I (422–432) not under Pope Sixtus III (432–440), who consecrated the basilica on the 5th of August 434 to the Virgin Mary.

The dedicatory inscription on the triumphal arch, Sixtus Episcopus plebi Dei (Sixtus the bishop to the people of God), is an indication of that Pope’s role in the construction.[26] As well as this church on the summit of the Esquiline Hill, Pope Sixtus III is said to have commissioned extensive building projects throughout the city, which were continued by his successor Pope Leo I, the Great.

The church retains the core of its original structure, despite several additional construction projects and damage by the earthquake of 1348.

Church building in Rome in this period, as exemplified in Santa Maria Maggiore, was inspired by the idea of Rome being not just the centre of the world of the Roman Empire, as it was seen in the classical period, but the centre of the Christian world. Santa Maria Maggiore, one of the first churches built in honour of the Virgin Mary, was erected in the immediate aftermath of the Council of Ephesus of 431, which proclaimed Mary Mother of God. Pope Sixtus III built it to commemorate this decision.

Certainly, the atmosphere that generated the council gave rise also the mosaics that adorn the interior of the dedication: “whatever the precise connection was between council and church it is clear that the planners of the decoration belong to a period of concentrated debates on nature and status of the Virgin and incarnate Christ.” The magnificent mosaics of the nave and triumphal arch, seen as “milestones in the depiction” of the Virgin, depict scenes of her life and that of Christ, but also scenes from the Old Testament: Moses striking the Red Sea, and Egyptians drowning in the Red Sea.

Richard Krautheimer attributes the magnificence of the work also to the abundant revenue accruing to the papacy at the time from land holdings acquired by the Catholic Church during the 4th and 5th centuries on the Italian peninsula: “Some of these holdings were locally controlled; the majority as early as the end of the 5th century were administered directly from Rome with great efficiency: a central accounting system was involved in the papal chancery; and a budget was apparently prepared, one part of the income going to the papal administration, another to the needs of the clergy, a third to the maintenance of church buildings, a fourth to charity. These fines enabled the papacy to carry out through the 5th century an ambitious building program, including Santa Maria Maggiore.”

Miri Rubin believes that the building of the basilica was influenced also by seeing Mary as one who could represent the imperial ideals of classical Rome, bringing together the old Rome and the new Christian Rome: “In Rome, the city of martyrs, if no longer of emperors, Mary was a figure that could credibly carry imperial memories and representations.”

Gregory the Great may have been inspired by Byzantine devotions to the Theotokos (Mother of God) when after becoming Pope during a plague in 590 that had taken the life of his predecessor, he ordered for seven processions to march through the city of Rome chanting Psalms and Kyrie Eleison, in order to appease the wrath of God. The processions began in different parts of the city, but rather than finally converging on St Peter’s, who was always the traditional protector of Rome, he instead ordered the processions to converge on Mary Major instead.

When the popes returned to Rome after the period of the Avignon papacy, the buildings of the basilica became a temporary Palace of the Popes due to the deteriorated state of the Lateran Palace. The papal residence was later moved to the Palace of the Vatican in what is now Vatican City.

The basilica was restored, redecorated and extended by various popes, including Eugene III (1145–1153), Nicholas IV (1288–92), Clement X (1670–76), and Benedict XIV (1740–58), who in the 1740s commissioned Ferdinando Fuga to build the present façade and to modify the interior. The interior of the Santa Maria Maggiore underwent a broad renovation encompassing all of its altars between the years 1575 and 1630.

On 15 December 2015, a Palestinian and a Tunisian national were arrested after they tried to disarm soldiers stationed outside the basilica while yelling “Allah (God) is great”. When police intervened, the two men aged 40 and 30 called other foreigners in the area to their aid, and assaulted and threatened the arresting officers.

Architecture

Architectural Styles: Romanesque Architecture, Baroque Architecture, Ancient Roman Architecture, Medieval Architecture.

The original architecture of Santa Maria Maggiore was classical and traditionally Roman, perhaps to convey the idea that Santa Maria Maggiore represented old imperial Rome as well as its Christian future. As one scholar puts it, “Santa Maria Maggiore so closely resembles a second-century imperial basilica that it has sometimes been thought to have been adapted from a basilica for use as a Christian church. Its plan was based on Hellenistic principles stated by Vitruvius at the time of Augustus.”

Even though Santa Maria Maggiore is immense in its area, it was built to plan. The design of the basilica was a typical one during this time in Rome: “a tall and wide nave; an aisle on either side; and a semicircular apse at the end of the nave.” The key aspect that made Santa Maria Maggiore such a significant cornerstone in church building during the early 5th century were the beautiful mosaics found on the triumphal arch and nave.

The Athenian marble columns supporting the nave are even older, and either come from the first basilica, or from another antique Roman building; thirty-six are marble and four granite, pared down, or shortened to make them identical by Ferdinando Fuga, who provided them with identical gilt-bronze capitals. The 14th-century campanile, or bell tower, is the highest in Rome, at 246 feet, (about 75 m.). The basilica’s 16th-century coffered ceiling, to a design by Giuliano da Sangallo, is said to be gilded with gold, initially brought by Christopher Columbus, presented by Ferdinand and Isabella to the Spanish pope, Alexander VI.

The apse mosaic, the Coronation of the Virgin, is from 1295, signed by the Franciscan friar, Jacopo Torriti. The Basilica also contains frescoes by Giovanni Baglione, in the Cappella Borghese. The 12th-century façade has been masked by a reconstruction, with a screening loggia, that was added by Pope Benedict XIV in 1743, to designs by Ferdinando Fuga that did not damage the mosaics of the façade. The wing of the canonica (sacristy) to its left and a matching wing to the right (designed by Flaminio Ponzio) give the basilica’s front the aspect of a palace facing the Piazza Santa Maria Maggiore.

To the right of the Basilica’s façade is a memorial constituting a column in the form of an up-ended cannon barrel topped with a cross: it was erected by Pope Clement VIII to celebrate the end of the French Wars of Religion. In the piazza in front of the facade rises a column with a Corinthian capital, topped with a statue of the Virgin and the child Jesus.

This Marian column was erected in 1614 to the designs of Carlo Maderno during the papacy of Paul V. Maderno’s fountain at the base combines the armorial eagles and dragons of Paul V (Borghese). The column itself was the sole intact remainder from the Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine in the Roman Forum. The statue atop the column was made by Domenico Ferri. In a papal bull from the year of its installation, the pope decreed three years of indulgences to those who uttered a prayer to the Virgin while saluting the column.

Salus Populi Romani (Our Lady of Roman People)

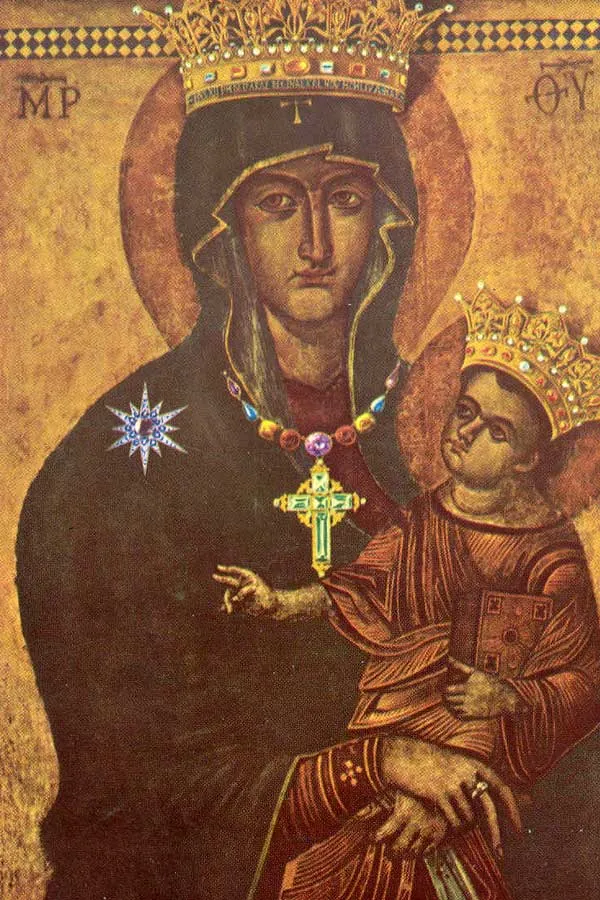

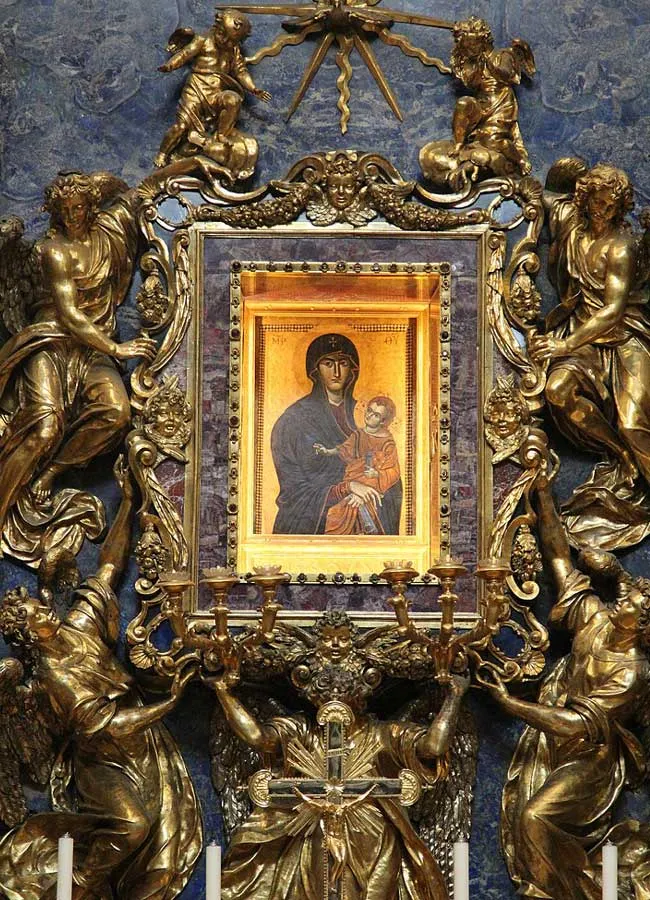

Salus Populi Romani (Protectress, or more literally health or salvation, of the Roman People) is a Roman Catholic title associated with the venerated image of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Rome. This Byzantine icon of the Madonna and Child Jesus holding a Gospel book on a gold ground, now heavily overpainted, is kept in the Borghese (Pauline) Chapel of the Basilica of Saint Mary Major.

The image arrived in Rome in 590 A.D. during the reign of Pope Gregory I. Pope Gregory XVI granted the image a canonical coronation on 15 August 1838 through the papal bull Cælestis Regina. Pope Pius XII crowned the image again and ordered a public religious procession during the Marian year of 1 November 1954. The image was cleaned and restored by the Vatican Museum, then given a Pontifical Mass on 28 January 2018.

The phrase Salus Populi Romani goes back to the legal system and pagan rituals of the ancient Roman Republic. After the legalisation of Christianity by Emperor Constantine the Great through the Edict of Milan in 313 AD, the phrase was sanctioned as a Marian title for the Blessed Virgin Mary.

History of Salus Populi Romani

The image is held to have arrived from Crete in the year 590 AD during the Pontificate of Pope Gregory the Great, who welcomed the image in person on its arrival borne with a floral boat from the Tiber river. For centuries it was placed above the door to the baptistery chapel of the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore where in the year 1240 it began to be called Regina Caeli (“Queen of Heaven”) in an official document.

Later it was moved to the nave, and from the 13th century it was preserved in a marble tabernacle. Since 1613 it has been located in the altar tabernacle of the Cappella Paolina that was built specifically for it, later known to English-speaking pilgrims as the Lady Chapel. The church and its Marian shrine are under the special patronage of the popes.

From at least the 15th century, it was honored as a miraculous image, and it was later used by the Jesuit Order in particular to foster devotion to the Mother of God through the Sodality of Our Lady movement.

The Roman Breviary states, “After the Council of Ephesus (431) in which the Mother of Jesus was acclaimed as Mother of God, Pope Sixtus III erected at Rome on the Esquiline Hill, a basilica dedicated to the honor of the Holy Mother of God. It was afterward called Saint Mary Major and it is the oldest church in the West dedicated to the honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary.”

Dating by Art Historians

The image “has been confidently dated to almost every possible period between the fifth century and the thirteenth”. The recent full-length study by Gerhard Wolf says, cautiously, that it is “probably Late Antique” in its original form.

The icon in its current state of overpainting seems to be a work of the 13th century (as witnessed by the features of the faces), but other layers visible under the top one suggest it is a repainting of a much earlier piece; especially revealing is the modeling of Child’s right hand in the first layer, which can be compared to other early Christian icons that display ‘Pompeian’ illusionistic qualities.

The areas of linear stylization, such as Christ’s garment which is rendered in golden hatching producing a flat effect, seem to go back to the 8th century, and can be compared with a very early icon of Elijah from Mount Sinai. A second restoration process started around 1100 and came to an end in the 13th century. The Virgin’s blue mantle which is wrapped over her purple dress was severely altered in the outline; the red halos are also not part of the original image.

The image type itself suggests it is not a medieval invention, but rather an Early Christian concept dating from antiquity: a majestic, half-length portrait showing a frank outward gaze of the rulerlike Virgin, with her upright, stately pose and folded hands gently clasping the Child, unique among all icons. Lively turning of the maturely developed and attired Child also attests to the painting’s antiquity.

The vivid contrapposto of the two bodies, which suggests direct observation, can be compared with a 5th-century Mount Sinai icon of the Virgin and Child in Kiev, and contrasted with the Pantheon Marian icon from 609, which already shows the Mother slightly subordinated to the Child by the imploring gesture and the turn of the head, and where the interaction of the bodies exists only in a flat plane. These comparisons suggest a date of the 7th century for the icon.

The early fame of the icon can be gauged from the production of replicas and the role it played in the ritual on the feast of the Virgin’s Assumption, where the Acheiropoieta was moved in a procession to Santa Maria Maggiore to ‘meet’ with it. Monneret de Villard has shown that engravings of this icon brought by Jesuits to Ethiopia influenced the art of that country from the 17th century onwards. More far flung apparent copies include a Moghul miniature, presumably based on a copy given to Akbar by the Jesuits, and copies in China, of which a 16th-century example is in the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

Cappella Sistina and Crypt of the Nativity

Under the high altar of the basilica is the Crypt of the Nativity or Bethlehem Crypt, with a crystal reliquary designed by Giuseppe Valadier said to contain wood from the Holy Crib of the nativity of Jesus Christ. Here is the burial place of Jerome, the 4th-century Doctor of the Church who translated the Bible into the Latin language (the Vulgate).

Fragments of the sculpture of the Nativity believed to be by 13th-century Arnolfo di Cambio were transferred to beneath the altar of the large Sistine Chapel off the right transept of the church. This chapel of the Blessed Sacrament is named after Pope Sixtus V, and is not to be confused with the Sistine Chapel of the Vatican, named after Pope Sixtus IV. The architect Domenico Fontana designed the chapel, which contains the tombs of Sixtus V himself and of his early patron Pope Pius V. The main altar in the chapel has four gilded bronze angels by Sebastiano Torregiani, holding up the ciborium, which is a model of the chapel itself.

Beneath this altar is the Oratory or Chapel of the Nativity, on whose altar, at that time situated in the Crypt of the Nativity below the main altar of the church itself, Ignatius of Loyola celebrated his first Mass as a priest on 25 December 1538. Just outside the Sistine Chapel is the tomb of Gianlorenzo Bernini and his family.

The Mannerist interior decoration of the Sistine Chapel was completed (1587–1589) by a large team of artists, directed by Cesare Nebbia and Giovanni Guerra. While the art biographer, Giovanni Baglione allocates specific works to individual artists, recent scholarship finds that the hand of Nebbia drew preliminary sketches for many, if not all, of the frescoes. Baglione also concedes the roles of Nebbia and Guerra could be summarized as “Nebbia drew, and Guerra supervised the teams”.

Feast Day - 5th August

On 12 November 1964, Blessed Pope Paul VI made a pilgrimage to the basilica and solemnly proclaimed Our Lady “Mother of the Church.” On 5 August the anniversary of the miraculous snow fall, the Feast of Our Lady of Snows is celebrated at the basilica of her name. White petals are scattered throughout the Basilica.

Mass Time

Weekdays

Sundays

Church Visiting Time

Contact Info

Piazza di Santa Maria Maggiore,

00100, Rome RM, Italy.

Phone No.

Tel : +39 06 6988 6800

Accommodations

How to reach the Basilica

Giovan Battista Pastine International Airport in Italy is the nearby Airport to the Basilica.

Farini Transit Stop in Rome, Italy is the nearby Transit Station to the Basilica.