Introduction

Strasbourg Cathedral or the Cathedral of Our Lady of Strasbourg (French: Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Strasbourg, or Cathédrale de Strasbourg, German: Liebfrauenmünster zu Straßburg or Straßburger Münster), also known as Strasbourg Minster, is a Catholic cathedral in Strasbourg, Alsace, France. Although considerable parts of it are still in Romanesque architecture, it is widely considered to be among the finest examples of Rayonnant Gothic architecture.

Architect Erwin von Steinbach is credited for major contributions from 1277 to his death in 1318, and beyond through his son Johannes von Steinbach, and his grandson Gerlach von Steinbach, who succeeded him as chief architects.

The Steinbachs’s plans for the completion of the cathedral were not followed through by the chief architects who took over after them, and instead of the originally envisioned two spires, a single, octagonal tower with an elongated, octagonal crowning was built on the northern side of the west facade by master Ulrich von Ensingen and his successor, Johannes Hültz. The construction of the cathedral, which had started in the year 1015 and had been relaunched in 1190, was finished in 1439.

Standing in the centre of Place de la Cathédrale, at 142 metres (466 feet), Strasbourg Cathedral was the world’s tallest building from 1647 to 1874 (227 years), when it was surpassed by St. Nikolai’s Church, Hamburg. Today it is the sixth-tallest church in the world and the highest still standing extant structure built entirely in the Middle Ages.

The construction, and later maintenance, of the cathedral is supervised by the Fondation de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame (“Foundation of Our Lady”) since at least 1224. The Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame, a municipal museum located in the Foundation’s buildings, displays original works of art from the cathedral, such as sculptures and stained-glass, but also the surviving original medieval buildings plans.

In 1988, the Strasbourg Cathedral was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List along with the historic centre of the city (called the “Grande Île”) because of its outstanding Gothic architecture.

History of Strasbourg Cathedral

The history of Strasbourg’s cathedral is well documented thanks to the archives of the Notre-Dame Foundation, the city of Strasbourg, and of the diocese. A Roman settlement called Argentoratum, twenty hectares in size, existed on the site since about 12 B.C., at a strategic point where bridges crossed the Rhine and two of its tributaries.

It became a major trading centre for wine, grain, and later for textiles and luxury products. Christianity was first imposed in 313 by the Edict of Constantine. The first recorded bishop, Amand, participated in the Councils of Cologne and Sardique in 346 and 347. A paleochristian church or cathedral is believed to have been founded by an edict of Clovis I, but its exact location and appearance is unknown.

The first cathedral built on the present site was erected by the bishop Saint Arbogast in about 550–575. Under Charlemagne, the Bishop Remi consecrated the altar and built a funeral crypt in about 778. This Carolingian church is believed to have had an apse flanked by two chapels and a nave covered with a wooden beamed roof, but no trace remains today.

Later History

In the late Middle Ages, the city of Strasbourg had managed to liberate itself from the domination of the bishop and to rise to the status of Free Imperial City. The outgoing 15th century was marked by the sermons of Johann Geiler von Kaisersberg and by the emerging Protestant Reformation, represented in Strasbourg by figures such as John Calvin, Martin Bucer and Jacob Sturm von Sturmeck. In 1524, the city council assigned the cathedral to the Protestant faith, while the building suffered some damage from iconoclastic assaults.

After the annexation of the city by Louis XIV of France, on 30 September 1681, and a mass celebrated in the cathedral on 23 October 1681 in presence of the king and prince-bishop Franz Egon of Fürstenberg, the cathedral was returned to the Catholics and its inside redesigned according to the Catholic liturgy of the Counter-Reformation. In 1682, the choir screen (built in 1252) was broken out to expand the choir towards the nave. Remains of the choir screen are displayed in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame and in The Cloisters.

The French Revolution and 19th Century

Following the outbreak of the French Revolution, on 2 November 1789, all church property was seized by the French state and was soon vandalised by the most ardent revolutionaries, the Enragés. The Director of public works of Strasbourg, Gérold, quickly took down and protected the statues of the portal, but 215 statues of the voussures over the portals were smashed with hammers, as were the angels atop the gables on the facade, and the crowns and sceptres of the statues of the kings.

The sculpture over the central tympanum and over the south portal of the transept was saved because it was covered with wooden planks with the revolutionary motto “Liberté-Egalité-Fraternité”.

In April 1794, the Enragés started planning to tear the spire down, on the grounds that it hurt the principle of equality. The tower was saved, however, when in May of the same year citizens of Strasbourg crowned it with a giant tin Phrygian cap of the kind the Enragés themselves wore. This artifact was later kept in the historical collections of the city until they were all destroyed during the Siege of Strasbourg in a massive fire in August 1870.

Seven church bells were removed and melted down to made into cannon, and gold and other precious objects in the interior confiscated and taken away, and in November 1793 the cathedral was formally proclaimed a “Temple of Reason.”

The cathedral was not returned to church control until July 15, 1801, along with confiscated property that had not been destroyed. The sculpture of the portals was returned to its places or restored between 1811 and 1827. However, the official ownership of the structure was given, and belongs today, to the French state, and it is administered by the Mayor of Strasbourg.

20th - 21st Century

In 1903, the architect Johann Knauth discovered cracks on the first pillar of the northern side of the nave. In 1905 he began taking measures to consolidate and strengthen the north side of the west facade, which supports the spire. After trying several temporary measures, in 1915, during the First World War, he launched a large-scale project to replace the entire foundation of the cathedral with concrete. This project was completed in 1926, after the end of the war. In 1918 Alsace and Strasbourg and Alscace were once again attached to France.

The cathedral was hit by British and American bombs during air raids on the centre of Strasbourg on 11 August 1944, which also heavily damaged the Palais Rohan and the Sainte-Madeleine Church. In 1956, the Council of Europe donated the famous choir window by Max Ingrand, the “Strasbourg Madonna” (see also Flag of Europe Biblical interpretation). Repairs to war damage were completed only in the early 1990s.

In October 1988, when the city celebrated its 2,000th anniversary (as the first official mention of Argentoratum dates from 12 BC), pope John Paul II visited and celebrated mass in the cathedral. The bishopric of Strasbourg had been elevated to the rank of archbishopric a few months before, in June 1988. In 2000, an Al-Qaeda plot to bomb the adjacent Christmas market was prevented by French and German police.

The restoration of the tower was completed in 2006, and in 2014 a new campaign of restoration was begun on the south transept.

Exterior - The West Front

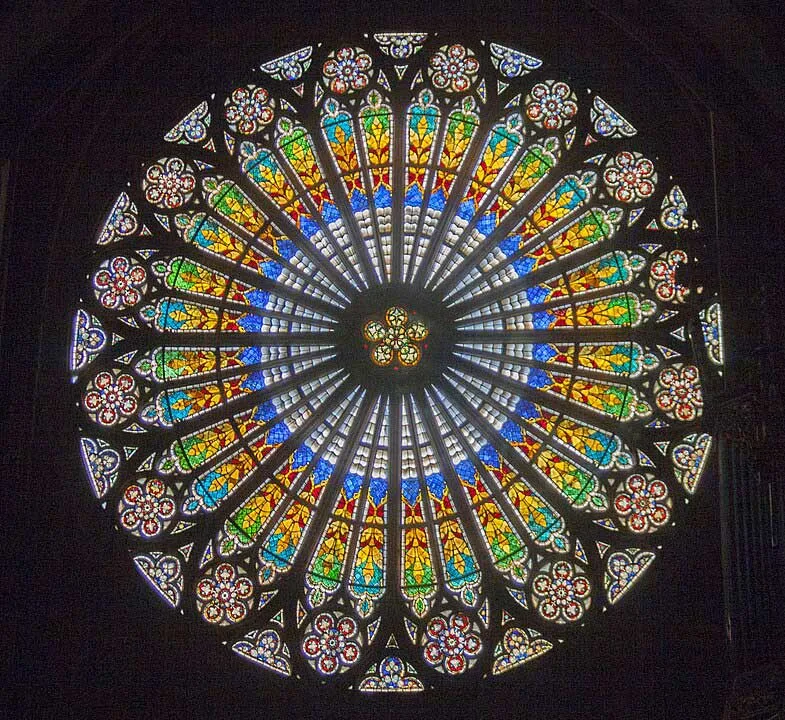

The west front or façade, the main entrance of the cathedral, is a relatively late addition, constructed between 1275 and 1399. The façade is supported and divided vertically by four narrow buttresses, each decorated with sculpture. It rises in three levels; the portals on the ground level; the level of the rose window above them, and the top level, with a balustrade. The rose window, with a rayonnant Gothic design, is fourteen metres in diameter and was finished in 1345. The pointed gable over the central portal, decorated with a sculpture of the Virgin Mary and child, reaches up into the space in front of the rose window. A gallery of statues of the Apostles, each in his own arch, is placed above the rose window.

The west front takes its distinctive appearance and sense of verticality from the dense network of lacelike pointed gables, pinnacles and tall, slender columns that cover it. The columns are purely decorative, and are so thin they are compared to the strings of a harp. The visual effect of the façade is enhanced by its unusual darkish red stone.

West Portals

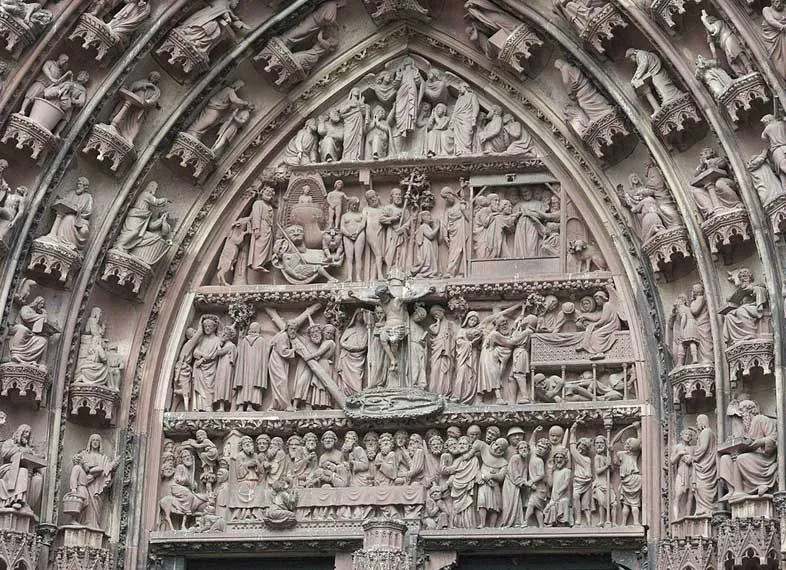

The cathedral has three portals, corresponding to the three vessels of the nave. Each has a particular theme of decoration; the left portal is dedicated to the infancy of Christ, the central portal to redemption, and the right portal to the Last Judgement. The portals are set forward from the front of the church by the network of slender columns, spires and arches which form an outer decorative wall. The sculpture largely dates to the late 13th century and is similar in theme and style to that of the sculpture of Reims Cathedral made between 1250 and 1260, though the Strasbourg sculpture shows greater realism.

The arched tympanum over the doors of the central portal is crowded with sculpture, as are the voussures, the stone arches around the door. The central figures depict the entry of Christ into Jerusalem, and the Crucifixion and Passion of Christ, all with exceptional expression and detail.

Unlike the sculpture of earlier cathedrals, the Strasbourg statues clearly show emotions; the prophets look severe, the Virgins appear serene, the Virtues look noble, and the frivolous Virgins appear foolish. The statues in the portals are all standing upon realistically carved capitals decorated with the signs of the zodiac.

Portal of Saint Lawrence (North Transept)

The portal of Saint Lawrence, was added to the north transept between 1495 and 1505 by Jacob von (or Jacques de) Landshut, with sculptures by Hans von Aachen (aka Johan von Ach, or Jean d’Aix-la-Chapelle) and Conrad Sifer. The original statues were replaced by copies in the 20th century and are today kept in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame. The tympanum was destroyed in the French Revolution and replaced by a work by the sculptor Jean Vallastre [fr] (1765–1833).

It presents a virtual theater of late Gothic flamboyant architecture and decoration, including three interlocking arches over the doors, containing a statue of the Saint during his martyrdom. The supporting buttresses on either side also have very expressive sculpture representing the Virgin Mary and the three Magi on one side, and a group of Saints on the other, both sheltered beneath lacelike flamboyant sculpture and pinnacles. A balustrade crosses the face of the transept, and above is a wall of two bays filled with stained glass.

Portal of the Virgin (South Transept)

The south portal, or Portal of the Virgin, dates to about the 1220s, the same time as the Pillar of the Angels and the Astronomic clock in the interior. Decrees of the Emperor rendering justice were traditionally read out in front of this doorway. The rounded arches of tympanum over the doorway contain sculpture of the Virgin Mary dying, surrounded by the Twelve Apostles and being crowned by Christ. The original statue-columns of the Apostles from the 1220s which supported the tympanum were smashed in 1793 during the French Revolution.

The mid-level of the transept over the portal, built in about 1230, has lancet windows and a statue of Virgin, flanked by Saint Peter and Saint Lawrence. Above this is a colourful clock with the signs of the zodiac. Above this is a flamboyant Gothic balustrade with an original sundial from about 1493, and above that are two small rose windows from the same period. Following their destruction during the French Revolution, several of the sculptures have been replaced in the 19th century by works by Philippe Grass, Jean-Étienne Malade, and Jean Vallastre.

As with all the other portals, several of the statues have been replaced by copies in situ and are today displayed in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame. This is also true for Ecclesia and Synagoga, arguably the most famous statues of the cathedral, if not of Strasbourg.

Octagon Bell Tower and Spire

The cathedral was originally intended to have two towers on the west front, but only the north one was built. The octagon tower was begun in 1399 by Ulrich von Ensingen (chief architect until 1419), and crowned with a spire by his successor Johannes Hültz. The work was completed in 1439.

The eight-sided tower is three times higher than wide, more elongated than other Gothic towers of the 14th century. It is surrounded and supported by four more slender towers containing circular stairways. The walls of the tower have tall lancet openings, which show the bells and bring light into the interior, and are decorated on the exterior with interlocking pointed gables. Between the lower tower and spire there is a balustrade, almost hidden by pinnacles and other architectural decoration.

The spire above the tower is composed of eight stages of elaborate octagonal structure, linked together by interlaced arches and pinnacles, which contain a stairway to the lantern at the top. Originally the lantern was topped by a statue of the Virgin Mary, the patron saint of the cathedral, but in 1488 it was replaced by a fleuron, or flower-shaped ornament. This is crowned by the cross, which is surrounded by four smaller crosses and images of the host and chalice, elements of the liturgy of the Eucharist.

Crossing Dome and Chevet

The crossing dome is placed over the meeting point of the transept and the choir, and, like the bell tower, has eight sides. It was constructed beginning in about 1330, following the rebuilding of the transept. Its base is topped by a gallery with pointed arches, beneath a level with large arched bays, two on each side, side, divided by clusters of columns. Above this are blind arcades, an ornate cornice, and then a pointed roof with a pair of dormer or skylight windows, a small window above a large one, on each side, which brought light to the choir below.

The medieval crossing dome’s aspect was altered several times over the centuries. The currently visible, much higher crossing dome was designed in grand Romanesque Revival style by the architect Gustave Klotz, after the original dome had been heavily damaged by Prussian shelling during the Siege of Strasbourg. Klotz’s dome was in turn heavily damaged by bombing raids during World War II, and restored between 1988 and 1992.

The chevet, at the northeast end of the cathedral, close to the transept, has vestiges that go back to the Romanesque cathedral, particularly at the lower levels. It looks over the former cloister of the canons of the cathedral. It is the least decorated side of the cathedral. A large arched bay occupies the central portion, just below a balustrade. Above that are three narrow windows and then a triangular gable with a small circular oculus window and blind arches. The face is flanked by two cylindrical towers with narrow lancet windows and pointed roofs. The walls are pierced with narrow slits, like a medieval fortress, giving it a very military appearance.

Two chapels, devoted to Saint Andrew and Saint John the Baptist, were attached to the two sides of the apse. The Chapel of John the Baptist preserves its thick Romanesque walls and two Romanesque windows.

Narthex

The narthex is the portion of the cathedral just inside the west front, beneath the tower. It is separated from the nave by two massive pillars, 8.5 by 5 meters, which support the tower above. The primary decorative element is the rose window, added between 1320 and 1340, and substantially restored since. Rays of yellow glass radiate outwards like a sun, surrounded mosaic-like pieces of green and blue and by small oculi with red floral designs. The tracery and decoration of the interior are very much like of that exterior, with blind galleries and delicate parallel vertical lines, like the strings of a harp. A pointed arch frames the window, and a row of blind arches at the lower level completes the decoration.

The reverse of the central doors of the portal has a column statue of Saint Peter holding the keys of the kingdom and above it a blind rose, without glass, a miniature version of the large rose window above it.

Stained Glass of Narthex

The lower bay on the south has stained glass windows that depict the Last Judgement, while the north bay windows illustrate twelve episodes from the Book of Genesis, including the creation of Adam and Eve, the original sin, the expulsion from Paradise, and Noah’s ark. These windows date to about 1345.

Nave

The nave is the section of the cathedral between the narthex and the choir where ordinary parishioners are seated and worship. At Strasbourg it is 61.5 metres (202 ft) long and 16 metres (52 ft) wide, not counting the two collateral aisles, which are each 10.41 metres (34.2 ft) wide. In height to the vaults it is 32.616 metres (107.01 ft). It takes its reddish-brown color from the sandstone of the Vosges mountains. The nave is dominated by the two rows of massive pillars. Each pillar bundles sixteen smaller columns, of which five reach upward to support the vaults overhead. The meeting points between the columns and the vault ribs is decorated with vegetal sculpture.

The elevation has the traditional High Gothic or Rayonnant Gothic three levels; large arcades below, with windows on the collateral aisles; a narrow triforium, or gallery, also with windows, for passing along the walls; and above that, of equal height with the arcades the upper windows which reach up into the vaults. The upper windows at Strasbourg fill the entire space between the triforium and the vaults. An additional element of decoration is given by the small sculpted, painted, and gilded heads on the keystones of the vaults, where the ribs meet.

Pulpit

The pulpit, attached to the fourth pillar of the north side of the nave, was sculpted in 1485 following a design by Hans Hammer. It is reached by a stairway with a curling sculpted design called “butterfly wings”. The pulpit itself, in the form of a very ornate corbeille or basket, is entirely covered with colonettes, gables, pinnacles, and niches filled with sculpture, including images of Christ on the cross, a crowned Virgin Mary, Apostles, the Crucifixion, and well as Kings and doctors of the Church.

A statue on the west side of the pillar represents a famed preacher contemporary with the cathedral; Johann Geiler von Kaysersberg (1510); a small sculpture along the railing of the stairs depicts Geiler’s dog, mourning his master on steps of the pulpit where he once preached.

The Grand Organ

The grand organ, located high on the wall of the north side of the nave, is recorded as existing in 1260. It was rebuilt 1298, in 1324 to 1327, in 1384, 1430, and 1489 and finally in 1716 by André Silbermann. It was hoisted up to its present position in 1327. The ornate and colourful decoration of pinnacle, spires, and sculpture also hangs beneath the organ, including a moving figure of Samson opening the jaws of a lion. Other moving figures include a trumpet player carrying a banner and a pretzel vendor being offered flour, water, and salt by the caryatides on the console.

The Silbermann organ had three keyboards, thirty-nine jeux, or effects and two thousand, two hundred forty-two pipes. It was electrified after 1807, and was restored and modified several times, most recently in 1934–35 and in 1975–81, giving it the current forty-seven jeux.

In addition to the grand organ in nave, the cathedral has two smaller organs:

- Choir pipe organ, north side of the choir, Joseph Merklin, 1878.

- Crypt pipe organ, 1998.

Astronomical Clock

The astronomical clock, located in the south transept, is one of the most famous features of the cathedral. The first astronomical clock was installed in the cathedral from 1352–54 until 1500. It was called the Dreikönigsuhr (“three-king clock”), and was located at the opposite wall from where today’s clock is. At noon, a group of three mechanical kings would prostrate themselves before the infant Jesus, while the chimes of the clock sounded the hour.

In 1547 a new clock was begun by Christian Herlin and others, but the construction was interrupted when the cathedral was handed over to the Roman Catholic Church. Construction was resumed in 1571 by Conrad Dasypodius and the Habrecht brothers, and this clock was given a more ambitious program of mechanical figures. It was decorated with paintings by the Swiss painter Tobias Stimmer. This clock functioned until 1788, and can be seen today in the Strasbourg Museum of Decorative Arts. The present clock was built by Jean-Baptiste Schwilguẻ between 1837 and 1842.

Crypt

The cathedral has two Romanesque crypts, the oldest parts of the cathedral. The more recent one is under the transept, from about 1150, and the older one, under the apse, was built in about 1110 to 1120. They are covered with Romanesque groin vaults, formed by the intersection of rounded barrel vaults, and supported by massive cruciform pillars and cylindrical columns with palm leaf decoration on their capitals.

Some of the capitals also have sculpted monsters and lions on the corners. The larger crypt has three naves, of equal size, divided by slender columns. There are three stairways down to the crypt, the oldest, from the apse, dates to about 1150. The pilasters between the stairways are older, from 1015. Further modifications were made to the crypts in the 12th century.

Bells

In 1519 Strasbourg Cathedral commissioned Jerg von Speyer to create what was said to be the largest bell in Europe; 2.74 meters in diameter and weighing twenty tons. This enormous bell was installed but cracked shortly afterwards. Its place as the bourdon, or largest and deepest-sounding bell, was taken by an older bell, the “Totenglock”, or “Death bell”, which was traditionally used for mourning. It weighs 7.5 tons and 2.2 meters in diameter, and was cast in 1447 by Hans Gremp. It is still in place.

During the French Revolution nine bells were taken out and melted down to make cannon, but the “Totonglock” and a second bell, the “Zehrnerglock” (1.58 meters, 2.225 tons), made in Mathieu Edel in 1786, were preserved to ring the hours and serve as alarm bells for the city. More recently, a group of six modern bells was cast in Heidelberg between 1974 and 1976; they range from 1.7 meters to 0.9 meters in diameter, and from 3.9 to 5.7 tons in weight. Other two bells are from 1987 and 2006.

The four bells in the octagon tower are rung on the hour. These include an old bell made by Jean Rosier and Cesar Bonbon (1691). Another two old bells by Mathieu Edel (1787) ring on the quarter hours. An even older bell, by Jean Jacques-Miller (1595), repeats the sounding of the hours one minute later.

Under the roof of the Klotz tower are the six bells that ring the weekly masses but also the baptisms, marriages and deaths of parishioners.

Tapestries

The cathedral has a particularly fine group of fourteen tapestries depicting the life of the Virgin Mary. They were commissioned by Cardinal Richelieu for the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris, and were made to accompany a painting there, “The Vow of Louis XIII”. They were manufactured between 1638 and 1657 in Paris by Pierre Damour. They were purchased by the Chapter of Strasbourg Cathedral in 1739, and were an example of the importation of the French style of that period into Alsace. They are traditionally hung in the arcades of the nave during Advent.

Cathedral Art in Strasbourg Museums

The Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame, or Museum of the Work of Notre-Dame, is located in a medieval and Renaissance building not far from the cathedral, and displays a collection of some of the most delicate original works of sculpture and art from Cathedral, moved there to protect them from environmental damage. These include some of the original statues from the portals and façade dating from the 13th century, including the statues of “The Church” and “The Synagogue” from the portal of the south transept. The statue of the “Synagogue” is blindfolded, since Jews did not recognise the divinity of Christ. It also preserves the earliest plans of the cathedral, as well as paintings and tapestries and other objects.

Other objects and works from the cathedral, including the mechanism of the original astronomical clock, are found in the Musée des arts décoratifs de Strasbourg.

Feast Day - 15th August

The Feast Day of Strasbourg Cathedral, also known as Cathedral of Our Lady of Strasbourg (Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Strasbourg), is celebrated on August 15th. This date corresponds to the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which is a significant event in the Catholic calendar. The feast day is marked with religious ceremonies, processions, and special events, attracting both locals and visitors to honor the cathedral’s patroness and celebrate the religious heritage of Strasbourg, Alsace, France.

Mass Time

Weekdays

Saturdays

Sundays

Church Visiting Time

Contact Info

Place de la Cathédrale,

67000, Strasbourg, France.

Phone No.

Tel : +33 3 88 21 43 34

Accomodations

How to reach the Cathedral

Strasbourg International Airport in Entzheim, France is the nearby Airport to the Cathedral.

Langstross Grand’Rue Tram Stop in Strasbourg, France is the nearby Tram Station to the Cathedral.