Introduction

The Church of St Mary-le-Bow is a Church of England parish church in the City of London. Located on Cheapside, one of the city’s oldest and most important thoroughfares, the church was founded in 1080 by Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury.

Rebuilt several times over the ensuing centuries, the present church is the work of Sir Christopher Wren, widely acknowledged to be one of his finest creations. With its tall spire, it is still a landmark in the City of London, being the third highest of any Wren church, surpassed only by nearby St Paul’s Cathedral and St Bride’s, Fleet Street. At a cost of over £15,000, it was also his second most expensive, again only surpassed by St Paul’s Cathedral.

St Mary-le-Bow is internationally famous for its bells, which also feature in the nursery rhyme ‘Oranges and Lemons’. According to legend, Dick Whittington heard the bells calling him back to the city in 1392, leading him to become Lord Mayor. Traditionally, anyone born within earshot of the bells was considered to be a true Londoner, or Cockney.

The church suffered severe damage by the Luftwaffe in the Second World War as part of the Blitz, like many churches in London. The interior was reduced to a shell and though the tower survived, fire damage meant the bells crashed to the floor. The church was sympathetically restored to its pre-war condition by Laurence King from 1956 to 1964. The church was awarded Grade I listed status, the highest possible rating, on the National Heritage List for England, whilst still a shell in 1950.

History of St Mary-le-Bow Church, London

Though archaeological excavations suggest an earlier Saxon building may have stood on the site prior to the Norman Conquest, the first confirmed church dedicated to St Mary on Cheapside was built by Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1080.

Lanfranc, who was William the Conqueror’s archbishop brought over from Normandy, founded the church as part of the Norman policy of dominating London. Three major buildings were constructed as part of this policy; St Paul’s Cathedral, the Tower of London, and a church on Cheapside.

The church at Cheapside was dedicated to St Mary and was constructed from Caen stone from Normandy, the same stone used in the Tower of London. The architect for the Tower of London was Gundulf, Bishop of Rochester, who may have also designed the first St Mary-le-Bow. This early church was built on two levels, with a lower undercroft partially below street level and the upper church, built above it.

The lower church was constructed first and featured round stone arches, which were a novelty at the time. This led to the church being known as Sancta Maria de Arcubus (St Mary of the Arches), a name which eventually became St Mary-le-Bow, bow being an old name for arches.

11th and 12th Centuries

The church was nearing completion in 1091 when it was destroyed by a violent tornado, amongst the most powerful ever to strike England. Roof rafters measuring 27–28 feet (8.2–8.5 m) long were thrown up in the air and forced into the ground with such force that only their tips remained visible.

The lower church survived, but the upper church was damaged beyond repair. The church was rebuilt, possibly in facsimile, but was destroyed again just a hundred years later, in a fire in 1196. The fire was caused by fugitive William Fitz Osbert hiding in the church tower, and to coax him out, supporters of the Archbishop of Canterbury set fire to the church. Osbert was fatally stabbed as he fled.

Late Medieval Period

The church was rebuilt again in the early 13th century following the 1196 fire, becoming a peculiar of the Archbishops of Canterbury and their London headquarters. It became home to the Court of Arches, to which the church gave its name. The Court of Arches, which still has its home at St Mary-le-Bow today, was the ecclesiastical court of appeal for the Province of Canterbury, founded in 1251. This allegiance to Canterbury made it the second most important church in London, after St Paul’s Cathedral.

The tower partially collapsed in its south west corner in 1271, killing at least one civilian in Cheapside below, Laurence Ducket. The tower was not immediately repaired and was kept in use. From 1363 onwards, the tower’s principal use was the housing of the city’s curfew bell, rung at 9 pm every evening and being able to be heard as far away as Hackney Marshes.

Work to repair the tower was slow, with construction noted to take place in 1448, 1459 and 1479. The tower was finally completed in 1512, supporting a spectacular series of stone lanterns; four around the corners of the tower and one suspended in the centre by arches. These lanterns were designed to light the streets below.

Destruction during the Great Fire of London (1666)

Soon after midnight on Sunday, 2 September 1666, a fire started in Thomas Farriner’s bakery on Pudding Lane, 0.7 kilometres (0.43 mi) to the southeast of St. Mary-le-Bow. During the course of the night, the easterly wind spread the fire through the city, consuming 300 houses in the first night alone. The fire continued to grow, becoming a firestorm on Monday and sweeping west towards St Paul’s Cathedral.

St Mary-le-Bow was one of over fifty churches to catch fire during the firestorm, which was only extinguished on the Thursday. The church was nearly completely destroyed, except for the tower, which survived albeit with fire damage. Attempts were made to repair the tower, but they all ultimately failed: the tower was structurally compromised from the fire and was no longer strong enough to support the ringing of bells.

Wren Rebuilding

Following Christopher Wren’s appointment as the King’s Surveyor of Works in 1669, Wren’s office was contracted to rebuild the fifty one churches of the city consumed by the fire. The Rebuilding of London Act of 1670 provided the funds for this, as it included raising the tax on coal. Other than St Paul’s Cathedral, St Mary-le-Bow was considered the most important church in the city, and thus, according to a document dated to 13 June 1670, at the head of the list to be rebuilt. The mason’s contract for the rebuilding of St Mary-le-Bow was signed just under two months later, on 2 August.

Wren’s initial designs were for a simple three bay structure and short tower, the latter topped by a simple cupola. This was revised in the same year with a much taller tower and more intricate spire. The body of the church, inspired by the Basilica of Maxentius in Rome, was completed by 1673.

The tower, however, would take a further seven years to finish, being finally completed in 1680. The total cost of the rebuilding was £15,421 (equivalent to more than £2.3 million in 2021), the second most expensive of any of Wren’s churches, only surpassed by St Paul’s. The tower was rebuilt in Portland stone, the rest of the church in brick. The tower became such a landmark that it was known as the “Cheapside pillar”.

During the rebuilding, Wren moved the position of the tower to sit directly on Cheapside, whereas the Norman and Tudor towers had sat back from the road. Whilst building the foundations for the tower, Wren came across an old Roman causeway 18 feet (5.5 m) below ground level and 4 feet (1.2 m) deep, which provided a solid foundation. Wren also discovered the 11th century under croft below the ruins, but he was uninterested, believing it to be Roman. He only provided a trapdoor and ladder into the undercroft, which became the crypt for the church above it.

18th – 20th Centuries

In 1820, the upper part of the spire was rebuilt and repaired by architect George Gwilt. In 1850, the church finally ceased to become a peculiar, coming under the jurisdiction of the Diocese of London, ending a practice started six hundred years earlier. The church continued, however, to be the home of the Court of Arches. Further alterations took place in the late 19th century, with the removal of galleries in 1867 and additional modifications from 1878-1879.

In 1914, a stone from the crypt of the church was placed in Trinity Church, New York, to mark the fact that William III granted the vestry of Trinity Church the same privileges as St Mary-le-Bow vestry.

Second World War

Beginning in 1940, the Luftwaffe began bombarding British cities from the air, a campaign known as the Blitz; London was struck especially heavily. Throughout most of the campaign, St Mary-le-Bow suffered only minor damage. However, on the final night of the Blitz, 10–11 May 1941, the church took several direct hits. A major fire started, destroying most of the building except the outer walls and the tower. The tower was not directly hit, but the fires from the church interior spread, burning out the tower floors and causing its bells to crash to the floor. The use of Portland stone in the tower, rather than the brick used in the body of the church, contributed to its survival.

From 1956 to 1964, the church was sympathetically rebuilt and restored by Laurence King to Wren’s designs, at a cost of £63,000. The tower survived, mostly as Wren left it, but part of it required rebuilding due to fire damage weakening the walls. The church was reconstructed in 1964, achieving Grade I listed status whilst still a ruin in 1950.

Architecture

The church building has a rectangular plan, with the tower situated on the northwest corner, separated from the main body of the church by a vestibule. The design of the church is such that the chancel occupies the eastern end of the nave, both with north and south aisles, which are noted to be extremely narrow. A vestry adjoins the vestibule to the north of the north aisle.

Unusually, due to the addition of the vestibule separating the tower and nave, the building has a greater length north to south than east to west; measuring 79 feet (24 m) from east to west but 131 feet (40 m) from the north wall of the tower to the south wall of the nave. The total area of the church building is 761 square metres (8,190 sq ft), which according to the Church of England, makes it a “large” sized church building.

Exterior

The exterior of St Mary-le-Bow is mostly constructed from red brick with dressings of Portland stone, with the exception of the tower, which is built entirely from Portland stone. The three principle facades of the building (south, north and east) have gabled walls and pedimented centres, complete with triplets of round-headed windows. The most prominent aspect of the exterior is Wren’s imposing tower, measuring 30 feet (9.1 m) square externally and with a height of 221 feet 9 inches (67.6 m), it is the third highest of any Wren church.

The tower, constructed of Portland stone, is formed of four stages surmounted by an elaborate stone spire. The lowest stage has doorways in the north and west faces of the tower, set in substantial stone recess with added rustication. The recess has a round head and is flanked by Doric order columns, which support a moulded entablature above. The doorways inside these recesses are set between Tuscan order columns which support a Doric frieze.

The second and third stages of the tower are more simple in construction, with two large square windows to the second stage, and a single round-headed window to the third. The fourth stage, housing the bell chamber, has a large round-headed opening in each wall, divided into three sections by thin mullions and filled with louvre boards. Framing the bell openings are pairs of Ionic order pilasters supporting an entablature, above which is the parapet. The parapet comprises an open balustrade between four corner pinnacles, formed of four ogee scrolls topped with small stone vases.

The spire above the tower is also formed of four stages. The lowest stage is a circular drum-shaped structure surrounded by twelve columns which have carved acanthus capitals. These twelve columns support a cornice with modillion decoration. Above the cornice is a second open balustrade, similar in design to that on the top of the tower.

The second stage is formed of twelve curved flying buttresses which support a circular-shaped moulded cornice. The third stage stands on the base of the cornice, and is square in plan, with granite columns on the corners. These columns support the fourth and final stage of the spire, which takes the form of a tall, square, tapering pinnacle, surmounted by a ball and weathervane, the latter taking the shape of a winged dragon.

Interior

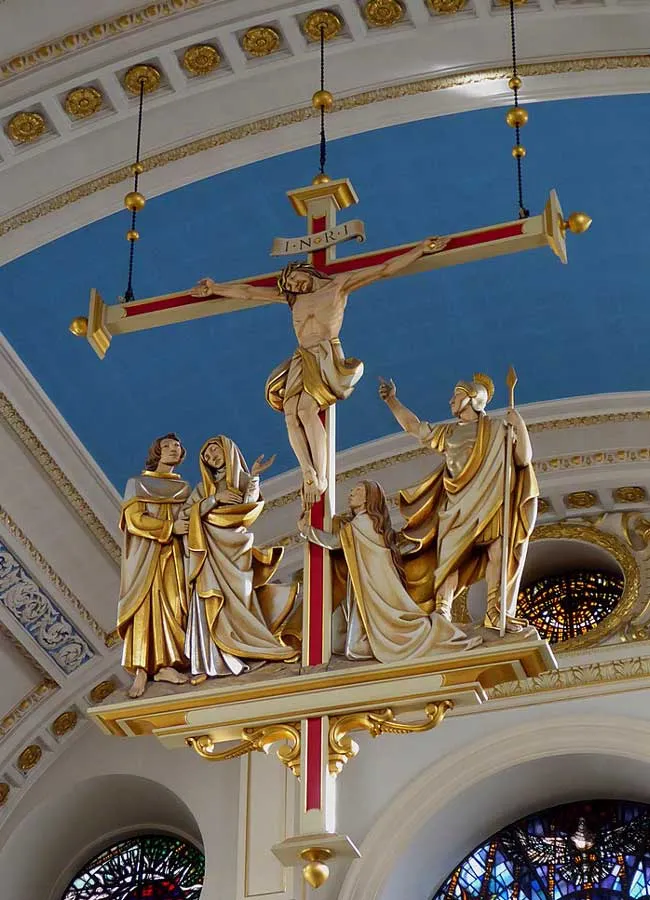

Only three bays make up the nave of the church, which is divided into small aisles by large round-headed arches. These arches are supported by compound piers with attached demi-columns that feature shorter pilasters for the openings and Corinthian capitals for the nave and aisles. The tunnel vault above the nave is covered in ornamental panelling that is painted blue and white and is penetrated by the clerestory windows.

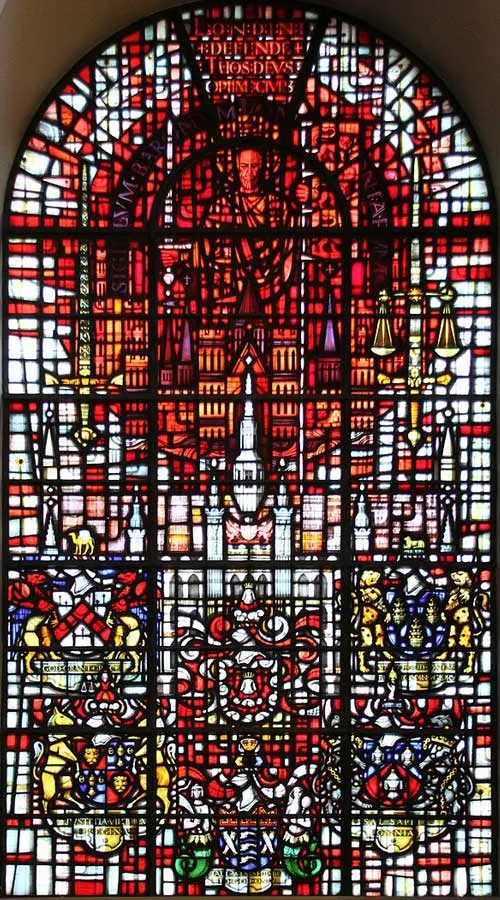

The church windows are among the structure’s most prominent elements following its 1964 restoration. They, along with the other furniture, vestments, etc., were created by John Hayward. All three of the east windows have rounded arches, although the central window is taller and wider than its neighbours, who have small round windows above them.

Linking the church and tower is a vestibule, featuring a tall groin-vaulted stone ceiling. The top of the vault is pierced by a removable circular trapdoor, opened to allow the bells to be lowered or raised from the tower.

Beneath the church, built on almost the same floor plan, is the 11th century crypt. The crypt, originally built as the under croft for the church destroyed in the tornado in 1091, is three bays in length and features Norman-era round arches, some of which contain Roman bricks, and a groined vault. The crypt is now in use as the “Cafe Below”.

Organ

The earliest record of an organ at the church dates to 1802 when Hugh Russell of London built a small instrument formed of 13 stops and 2 manuals. This organ, like its successors, was situated on a gallery above the west doors. This organ lasted until 1867, when George Maydwell Holdich, also of London, rebuilt and enlarged the organ. He added a third manual, a pedal board and 11 additional stops to make a total of 24.

In 1880, the organ was purchased by Walker & Sons at a cost of £255 and transferred to the Methodist Church at Thornton, Leicestershire. Walker & Sons constructed a new instrument for St Mary-le-Bow in the same year, at a cost of £1,108. This new instrument was much larger, formed of 33 stops and 3 manuals plus a pedalboard and was situated in the sanctuary at the eastern end of the church. This organ lasted unaltered until the Blitz, when following the first strike to hit the church, which only caused minor damage, it was removed for safekeeping by Rush worth and Draper.

Bells

The bells at St Mary-le-Bow are often considered to be the most famous peal in the world. According to legend, Richard (Dick) Whittington heard the bells in 1392 when he left the city, calling him back and leading him to become Lord Mayor. The earliest record of bells at the church, however, is in 1469, when the Common Council orders a curfew bell should be rung at St Mary-le-Bow at 9.00 each evening. In 1515, William Copland, one of Henry VIII’s merchants, gave money for a “great bell” to be installed, with directions it should be rung to announce the curfew. With Copland’s gift, the tower then contained five bells.

In the 1552 survey of church goods ordered by Edward VI, the tower is recorded as containing five bells with two additional “sanctus” bells. These five bells would later be augmented, when in 1635, six are recorded. In 1666, during the Great Fire of London, the bells and tower, along with the church, were damaged beyond repair.

Following the Great Fire and Wren’s rebuilding of the church, the tenor bell of a proposed ring of eight was cast by Christopher Hodson of St Mary Cray in 1669, placed in a temporary structure in the churchyard until the tower was completed. The bell weighed approximately 52 long cwt (2,600 kg). In 1677, Hodson cast the remaining seven and hung all eight bells in the newly completed tower in a new oak frame.

Selfridge's Ring

In January 1927, following the deterioration of the fittings and the condition of the tower, the bells were declared unringable in a report first published by The Times. Over the ensuing six years, much work was done to the tower and the church to restore it, but the bells remained unringable, to much public outcry. Finally, in 1933, Harry Gordon Selfridge offered to defray the cost of restoring the bells, an offer which was accepted by the church, who gave the contract to Gillett & Johnston, who Selfridge had worked with a few years previously on bells for his Oxford Street store.

The announcement that Gillett & Johnston intended to recast the tenor, which was believed to be cracked, caused so many objections that a meeting of the Province of Canterbury’s ecclesiastical court was called; the decision of the court was eventually that the tenor should be recast. Gillett & Johnston found upon removing the bells to their works in Croydon that four more of the bells (6, 7, 8 and 10) were cracked, in addition to the tenor.

All five cracked bells were recast in addition to the three lightest bells, leaving only the 4th, 5th, 9th and 11th from the previous ring to be retained; these four bells were retuned. The bells were rehung in their original frame with new cast iron headstocks, ball bearings and wrought iron clappers. The frame was substantially strengthened with a massive concrete and steel grillage weighing 3.5 long tonnes (3,556 kg). The bells were rededicated by the Archbishop of Canterbury on July 7, 1933.

Post-War Restoration

The damaged bells were removed shortly after their destruction to Mears & Stainbank’s foundry in Whitechapel, but they remained in storage for more than 10 years. In 1956, as the restoration of the church began, attention turned to the restoration of the tower and the recasting of the bells. Much of the cost of restoring the tower and bells was met by the Bernard Sunley Charitable Foundation and Trinity Church, Wall Street, New York City. A new ring of twelve was cast by Mears & Stainbank in 1956, partially reusing metal salvaged from the 1933 ring. However, due to the condition of the tower, which required repairs, the bells were not hung until late 1961.

The bells were dedicated in the presence of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh by Robert Stopford, Bishop of London, on 21 December 1961. The tenor was tolled by Prince Philip at the beginning of the service. The bells were hung in a new frame, made of Javanese Jang (Dipterocarpus terminatus). Since then, the bells have been frequently rung, both by members of the Ancient Society of College Youths who reside in or near the city, and by visiting bands of ringers, who come from across the world to ring the bells.

All the bells are named and each bell has an inscription from Psalms, the first letter of each forming the acrostic ‘D. Whittington’. The largest bell weighs 41 long cwt 3 qrs 21 lb (4,697 lb or 2,131 kg), the third heaviest tenor bell in London after St Paul’s and Southwark Cathedral.

Feast Day - 8th September

The Feast Day of St Mary-le-Bow Church in London, Cheapside, England is celebrated on September 8th. This date marks the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary and is a significant occasion for the church. The feast day is typically observed with special religious services, processions, and other festivities to honor the Virgin Mary and commemorate the religious heritage of St Mary-le-Bow Church.

Mass Time

Weekdays

Church Visiting Time

Contact Info

Cheapside, London,

EC2V 6AU, United Kingdom.

Phone No.

Tel : +44 20 7248 5139

Accommodations

How to reach the Church

London City Airport is a regional airport in London, England. It is located in the Royal Docks in the Borough of Newham is the nearby Airport to the Church.

Mansion House Subway Station in London, England is the nearby Train Station to the Church.