Introduction

St Giles’ Cathedral, or the High Kirk of Edinburgh, is a historic parish church of the Church of Scotland located in Edinburgh’s Old Town. Originally founded in the 12th century and dedicated to Saint Giles, the church was expanded in the 14th to 16th centuries, with significant 19th and 20th-century alterations including the addition of the Thistle Chapel. It became Protestant in 1559 under John Knox during the Scottish Reformation, and was later made the cathedral of the Diocese of Edinburgh in 1633. The church played a crucial role in Scottish history, notably during the Covenanters’ Rebellion in 1637, and is often referred to as “the Mother Church of World Presbyterianism.” With its medieval origins and significant architectural modifications, including those by William Burn and William Hay, St Giles’ remains a central site for important events and services, including those of the Order of the Thistle, and is a major visitor attraction in Scotland.

Saint Giles, the patron saint of lepers and associated with the Abbey of Saint-Gilles in France, was a popular figure in medieval Scotland. St Giles’ Church, originally associated with the Order of St Lazarus who ministered to lepers, was Edinburgh’s sole parish church before the Reformation. From its elevation to collegiate status in 1467 until the Reformation, it was known as “the Collegiate Church of St Giles of Edinburgh,” and after the Reformation, it was referred to as “the college kirk of Sanct Geill.” In 1633, it was made a cathedral but only held this status until 1638 and again between 1661 and 1689. After 1689, the Church of Scotland, being Presbyterian, did not have bishops or cathedrals, so St Giles’ retained its title as a former cathedral. The church has been known variously as St Giles’ Cathedral, St Giles’ Kirk, or simply St Giles’, with the title “High Kirk” briefly used in the early 17th century and revived in the late 18th century for the East Kirk. Since 1883, the entire building has been used by the High Kirk congregation.

St Giles’ Church, attributed to David I and founded around 1124, was likely established as a separate parish from St Cuthbert’s. During David’s reign, Edinburgh was elevated to burgh status, and the church, along with its lands known as St Giles’ Grange, came under the care of monks from the Order of Saint Lazarus. The original Romanesque church, which displayed architectural similarities to the church at Dalmeny, was consecrated on October 6, 1243, by Bishop David de Bernham of St Andrews, though this was likely a re-consecration due to a loss of records of the initial consecration.

Throughout its history, St Giles’ faced significant events and damage. In 1322, during the First Scottish War of Independence, it was possibly attacked by Edward II’s troops following their sacking of Holyrood Abbey. In 1384, Scottish knights used the church for secret meetings with French envoys, planning a raid into England, which led to Richard II’s retribution and the burning of Edinburgh, including St Giles’. The church, which had been Gothic since the 14th century, with its crossing and nave completed by 1387, faced further damage and restoration over the centuries. By the 1370s, the church was under the Scottish crown after support by the Lazarite friars for the English king. In 1393, Robert III granted the church to Scone Abbey, and subsequent records show that clerical appointments were made by the monarch, indicating the church likely reverted to the crown soon after.

In 1419, Archibald Douglas, 4th Earl of Douglas, led an unsuccessful petition to Pope Martin V to elevate St Giles’ to collegiate status, a request that was also denied in 1423 and 1429. However, a successful petition in 1466 led to St Giles’ being granted collegiate status by Pope Paul II in February 1467. This new foundation replaced the vicar with a provost, who was accompanied by a curate, sixteen canons, a beadle, a minister of the choir, and four choristers. During this period of petitioning, William Preston of Gorton brought the arm bone of Saint Giles from France with the permission of Charles VII, which became an important relic. To commemorate Preston, the Preston Aisle was added to the southern side of the choir in the mid-1450s, and Preston’s descendants were granted the honor of carrying the relic in the Saint Giles’ Day procession on September 1. Around 1460, Mary of Guelders supported the extension of the chancel and the addition of a clerestory, possibly in memory of her husband, James II.

Following its elevation to collegiate status, St Giles’ saw a significant increase in chaplainries and endowments, with possibly up to fifty altars by the time of the Reformation. In 1470, Pope Paul II further elevated the church’s status by granting a petition from James III to exempt St Giles’ from the jurisdiction of the Bishop of St Andrews. During Gavin Douglas’ provostship, St Giles’ played a central role in Scotland’s response to the national disaster of the Battle of Flodden in 1513, where the townspeople were ordered to defend Edinburgh while women prayed for James IV and his army. Requiem Mass and memorial services for the fallen were held at St Giles’, and Walter Chepman endowed a chapel of the Crucifixion in the kirkyard to honor the King’s memory.

The Reformation began to affect St Giles’ as early as 1535 when Andrew Johnston, a chaplain, was expelled for heresy. In October 1555, the town council burned English language books, likely Reformers’ texts, outside the church, and in 1556, images of the Virgin, St Francis, and the Trinity were stolen from St Giles’, potentially by reformers. In July 1557, the church’s statue of Saint Giles was stolen, drowned in the Nor Loch, and burned, leading John Knox to criticize the event. A replacement statue, borrowed from the Franciscans, was also damaged during disruptions by Protestants at the Saint Giles’ Day procession that year.

Reformation

At the beginning of 1559, amid the Scottish Reformation, the Edinburgh town council hired soldiers to protect St Giles’ from Reformers and distributed its treasures for safekeeping. On June 29, 1559, the Lords of the Congregation entered Edinburgh unopposed, and John Knox preached his first sermon at St Giles’, later being elected as its minister. The subsequent weeks saw the removal of Roman Catholic furnishings from the church. Mary of Guise, ruling as regent for her daughter Mary, proposed using Holyrood Abbey for Roman Catholics while St Giles’ served Protestants, with a promise to accept the dominant confession after January 1560. These proposals failed, and the Lords of the Congregation vacated Edinburgh after a truce with Catholic forces. Knox fled on July 24, 1559, but St Giles’ remained Protestant, with Knox’s deputy, John Willock, continuing to preach despite disruptions and using the church for practical purposes during the Siege of Leith. The Roman Catholic forces briefly retook Edinburgh, and on November 9, 1559, Nicolas de Pellevé reconsecrated St Giles’ as a Roman Catholic church. However, following the Treaty of Berwick and intervention by Elizabeth I of England, the Reformers retook Edinburgh, and St Giles’ reverted to Protestant status on April 1, 1560, with Knox returning on April 23, 1560. Scottish Parliament declared the Pope had no authority in Scotland from August 24, 1560. Subsequently, the church was cleared of Roman Catholic elements, whitewashed, and repurposed with new features including seating and a pulpit, while most burials shifted to Greyfriars Kirkyard after the kirkyard south of the church was closed in 1561.

Church and Crown : 1567 – 1633

In 1567, following the deposition of Mary, Queen of Scots, and the succession of her infant son, James VI, St Giles’ became a key site in the Marian civil war. After the assassination of Regent Moray in January 1570, he was interred in the church, and John Knox preached at his funeral. Edinburgh briefly fell to Mary’s forces, and in June and July 1572, William Kirkcaldy of Grange fortified the church with soldiers and cannon. Despite Knox’s declining health, he returned to St Giles’ for his final sermon on November 9, 1572, before passing away later that month; he was buried in the kirkyard with Regent Morton present. Post-Reformation, parts of St Giles’ were repurposed for secular uses. In 1562 and 1563, the western three bays were partitioned to extend the Tolbooth, serving as a venue for criminal courts, the Court of Session, and Parliament. The church also housed a prison for recalcitrant Roman Catholic clergy and other offenders, while the tower was used as a jail by the late 16th century. The Maiden, an early guillotine, was stored in the church, and the vestry was converted into an office and library for the town clerk, with weavers setting up looms in the loft.

Around 1581, St Giles’ interior was divided into two meeting houses: the chancel became the East (or Little or New) Kirk, and the crossing and nave were designated the Great (or Old) Kirk. These congregations, along with Trinity College Kirk and the Magdalen Chapel, were overseen by a joint kirk session. By 1598, the upper storey of the Tolbooth partition was converted into the West (or Tolbooth) Kirk. During James VI’s early reign, St Giles’ ministers, led by Knox’s successor James Lawson, became a significant spiritual force, challenging the King’s ecclesiastical proposals. The relationship between James and the Reformed clergy soured, particularly after a tumult at St Giles’ on December 17, 1596, which led to the King briefly retreating to Linlithgow and the ministers fleeing rather than facing him. To counter their influence, James implemented an order to divide Edinburgh into distinct parishes, effective from April 1598. By 1620, the Upper Tolbooth congregation had moved to the newly established Greyfriars Kirk.

Cathedral

Charles I first visited St Giles’ on June 23, 1633, during his coronation in Scotland, where he unexpectedly replaced the local reader with clergy performing the service according to the Church of England’s rites. Later that year, on September 29, Charles elevated St Giles’ to cathedral status, establishing it as the seat of the new Bishop of Edinburgh and initiating renovations to transform its interior to resemble Durham Cathedral. However, on July 23, 1637, a Scottish version of the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer replaced Knox’s Book of Common Order, leading to rioting, famously sparked by Jenny Geddes hurling a stool at the dean. This unrest resulted in the temporary suspension of services at St Giles’ and set off a series of events leading to the signing of the National Covenant in February 1638 and the Bishops’ Wars, a precursor to the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

In 1641, Charles I attended Presbyterian services at the East Kirk, influenced by the Covenanter Alexander Henderson, after having been compelled by the Treaty of Ripon to ratify Covenanter Parliament Acts. Following the Covenanter defeat at the Battle of Dunbar, Oliver Cromwell’s troops occupied the East Kirk as a garrison church, with Cromwell and General John Lambert preaching there. During the Protectorate, both the East and Tolbooth Kirks were partitioned. The Restoration in 1660 saw the removal of Cromwellian partitions and the reinstallation of a royal loft. In 1661, under Charles II, St Giles’ regained cathedral status, and the remains of James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose, were re-interred there. This led to further conflict with Covenanters, who were imprisoned in what was then called “Haddo’s Hole.” After the Glorious Revolution and the subsequent abolition of bishops in 1689, many ministers and congregants left the Church of Scotland to form the Scottish Episcopal Church, with notable congregations including Old St Paul’s emerging from St Giles’.

Four Churches : 1689 – 1843

In 1699, the northern half of the Tolbooth partition was repurposed into the New North (or Haddo’s Hole) Kirk. By 1707, the newly installed carillon at St Giles’ played the tune “Why Should I Be Sad on my Wedding Day?” to mark the Union of Scotland and England’s Parliaments. During the Jacobite rising of 1745, Edinburgh’s inhabitants met at St Giles’ to agree to surrender the city to Charles Edward Stuart’s advancing army. From 1758 to 1800, Hugh Blair, a key figure of the Scottish Enlightenment and a noted moderate preacher, served at the High Kirk, drawing notable figures like Robert Burns and Samuel Johnson. In contrast, Alexander Webster, his contemporary, preached strict Calvinist doctrine from the Tolbooth Kirk. At the start of the 19th century, the Luckenbooths and Tolbooth, which had encased the church’s north side, were demolished, revealing that the church’s exterior walls were leaning outward. In 1817, the city council commissioned Archibald Elliot to develop restoration plans, but due to controversy and insufficient funds, no restoration work was undertaken.

During his 1822 visit to Scotland, George IV attended service at the High Kirk, which spurred efforts to restore the deteriorating building. With £20,000 from the city council and government, William Burn led the restoration between 1829 and 1833. His alterations included encasing the exterior in ashlar, raising the roofline, and adding new doors, while restructuring the interior to accommodate separate churches in the nave and choir, and a meeting place for the General Assembly in the south. Burn also removed internal monuments and secular spaces like the police office. The restoration faced mixed reactions; while some praised the stabilization of the church, others, including Robert Louis Stevenson, criticized it for its perceived loss of character. Despite initial disapproval, Burn’s work is now acknowledged for preserving the church from collapse. The High Kirk returned to the choir in 1831, the Tolbooth Kirk to the nave in 1832, and the General Assembly, finding its new hall inadequate, met there only once in 1834 before the Old Kirk congregation moved in.

Victorian era

During the Disruption of 1843, key ministers from the High Kirk and other churches left the established church to join the newly formed Free Church, leading to a significant exodus of their congregations. The Old Kirk congregation was suppressed in 1860. In 1867, William Chambers, publisher and Lord Provost of Edinburgh, proposed restoring St Giles’ as a “Westminster Abbey for Scotland” and commissioned Robert Morham and later William Hay for the project. Supported by Lindsay Mackersy, Chambers’ ambitious restoration sought to beautify the church, introducing stained glass and an organ, despite some evangelical concerns about its resemblance to a Roman Catholic church. The restoration, which began in June 1872 and concluded in March 1873, included the removal of internal partitions and the replacement of pews with stalls and chairs. The restoration of the Old Kirk and West Kirk followed, beginning in January 1879, and by 1881, the West Kirk had vacated St Giles’. During this process, human remains were discovered and reinterred in Greyfriars Kirkyard. Chambers died on 20 May 1883, just before the restored church was officially opened by John Hamilton-Gordon, 7th Earl of Aberdeen, and his funeral was held in the newly restored church shortly after its reopening.

20th and 21st Century

In 1911, George V inaugurated the newly constructed chapel of the Order of the Thistle at St Giles’, located at the church’s southeast corner. The church later faced controversy when Wallace Williamson’s refusal to pray for imprisoned suffragettes led to disruptions by their supporters in late 1913 and early 1914. The impact of World War I was profound, with ninety-nine members of the congregation, including assistant minister Matthew Marshall, killed. St Giles’ hosted the lying-in-state and funeral of Elsie Inglis, a medical pioneer and congregation member, in 1917. The church was transferred from the City of Edinburgh Council to the Church of Scotland in 1929 ahead of the reunion of the United Free Church of Scotland and the Church of Scotland.

The church survived World War II unscathed and hosted a Thanksgiving service attended by the royal family the week after VE Day. The Albany Aisle was adapted as a memorial chapel for the 39 members of the congregation who died in the war. Elizabeth II visited St Giles’ on 24 June 1953 for a national service of thanksgiving marking her first visit to Scotland since her coronation. From 1973 to 2013, Gilleasbuig Macmillan served as minister, overseeing significant restorations and reorientations of the church. St Giles’ continues to function as an active parish church and major tourist attraction, drawing over 1.3 million visitors in 2018. Notably, on 12 September 2022, the cathedral hosted a service of thanksgiving for Queen Elizabeth II’s coffin, and on 5 July 2023, it was the venue for the presentation of the Honours of Scotland to King Charles III in a ceremony marking his coronation.

Architecture of St. Giles Cathedral Parish Church in Edinburgh, Scotland

The original St Giles’ was likely a modest Romanesque church from the 12th century, characterized by a rectangular nave and a semi-circular apsidal chancel. By the mid-13th century, a south aisle was added, and archaeological excavations in the 1980s revealed that the church was constructed from pink sandstone and grey whinstone. The church stood on a clay platform designed to level the steep slope of the site, surrounded by a boundary ditch. By 1385, this early structure was replaced by the core of the current church, which included a nave with five bays, transepts, a crossing, and a four-bay choir. The church underwent several extensions and modifications between 1387 and 1518, leading to a complex plan with numerous chapels and outer aisles, reflecting a blend of French medieval architectural influences.

Significant alterations to the church were minimal until the restoration led by William Burn from 1829 to 1833, which involved removing several bays, adding clerestories to the nave and transepts, and encasing the exterior in polished ashlar. William Hay further restored the church between 1872 and 1883, removing the remaining internal partitions and adding ground-level rooms around the periphery. The Thistle Chapel, designed by Robert Lorimer, was added to the southeast corner of the church between 1909 and 1911. The most substantial restoration occurred from 1979 onwards, led by Bernard Feilden and Simpson & Brown, which included leveling the floor and rearranging the interior around a central communion table.

Exterior

Before William Burn’s restoration from 1829 to 1833, St Giles’ Church had a “uniquely complex external appearance” due to numerous extensions, which resulted in a varied and intricate façade highlighted by numerous gables. The early 19th-century demolition of adjacent structures like the Luckenbooths and Tolbooth exposed the church’s walls, which were found to be leaning outward by up to one and a half feet in some places. To address this, Burn encased the exterior in polished gray sandstone from Cullalo in Fife, with the new layer varying in thickness from eight inches at the base to five inches at the top. He also collaborated with Robert Reid, architect of the nearby Parliament Square buildings, to ensure architectural harmony. Burn’s extensive alterations included expanding the transepts, adding a clerestory to the nave, and creating new doorways. The western façade was redesigned to be symmetrical, with a new west doorway featuring niches with statues of Scottish monarchs and church figures, crafted by John Rhind, while Skidmore produced the metalwork.

Burn’s restoration also involved removing several historical elements, including the westernmost bays of the south nave aisle and parts of the Holy Blood Aisle and north nave. These elements, likely dating from the late 15th century, were among the grandest porches in Scottish medieval churches, comparable to those at St John’s Kirk, Perth, and St Michael’s Kirk, Linlithgow. Burn replicated the grand porch arrangement in a new doorway at the west of the Moray Aisle. Prior to the restoration, the church’s windows featured various styles of tracery, but Burn retained the tracery of the great east window, restored by John Mylne the Younger in the mid-17th century, and introduced new tracery based on late medieval Scottish designs for the other windows.

Nave

The nave of St Giles’ Church is described as “archaeologically the most complicated part of the church” due to its extensive alterations and extensions since its original 14th-century construction. During William Burn’s 1829–1833 restoration, the nave’s central section was fitted with a tierceron vault in plaster and its walls were raised by 16 feet to include clerestory windows. Although Burn is often credited with removing a medieval vaulted ceiling, there is no contemporary evidence of this, and it may have been removed prior to his work. William Hay’s 1882 additions included new corbels and shafts for the vaults, and he also replaced Burn’s 15th-century-inspired pillars with replicas of the original 14th-century octagonal pillars. The original arcade was lower, with clerestory windows above each arch, evidenced by a fragment of an arch and the filled-in arches visible above the south nave arcade. The presence of taller arches nearest the crossing suggests an incomplete medieval attempt to heighten the arcade.

North Nave Aisle

The north nave aisle of St Giles’, dating to the turn of the 15th century, features a rib-vaulted ceiling similar in style to the Albany Aisle, which was added as an extension of the two westernmost bays. The Albany Aisle, comprising two bays with a stone rib-vaulted ceiling, was constructed with a bundled pillar supporting a foliate capital and octagonal abacus adorned with the escutcheons of its donors, Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany, and Archibald Douglas, 4th Earl of Douglas. This style of pillar was influential in later additions to the church. The aisle was believed to have been donated in penance for the donors’ involvement in the death of David Stewart, Duke of Rothesay. The Albany Aisle’s floor was originally paved with Minton tiles, which were later replaced by Leoch paving stones after World War II. East of the Albany Aisle, remnants of the 12th-century Norman north door are marked by two light-colored stones. This doorway, along with a porch and a turnpike stair, was removed during the Burn restoration, and the lancet arch now frames a memorial. To the east of this site is a recessed stoup. The St Eloi Aisle, the only one of two chapels north of the easternmost bays to survive the Burn restoration, features a barrel vault with original and new elements and contains a Romanesque capital rediscovered in 1880. Its floor is decorated with marble and mosaic panels by Minton, showcasing symbols associated with the Incorporation of Hammermen and the four evangelists.

South Nave Aisle

The inner and outer south nave aisles of St Giles’, begun in the later 15th century and completed by 1510, were constructed around the time of the Preston Aisle and replaced an earlier aisle and chapels mentioned in a 1387 contract. The inner aisle retains its original quadripartite vault, while the outer aisle, known as the Moray Aisle, features a plaster tierceron vault from the 19th-century restoration by William Burn, who also removed the two westernmost bays of this aisle. Burn’s restoration included adding a new wall with a door and oriel window at the west end and replacing the inner aisle’s window with a smaller one. In 1513, Alexander Lauder of Blyth commissioned the Holy Blood Aisle at the eastern end of the outer south nave aisle, which was completed in 1518 and named for the Confraternity of the Holy Blood. During Burn’s restoration, the western bay of this aisle and the separating pillar were removed, with the remaining space converted into a heating chamber, later restored to ecclesiastical use by William Hay. The south wall of the aisle features an elaborate late Gothic tomb recess.

Crossing and Transepts

The piers of the crossing in St Giles’ are likely the oldest parts of the present church, dating back to the 14th century. These piers were probably raised around 1400, coinciding with the creation of the current vault and bell hole. The initial stages of the transepts were completed by 1395, with the addition of the St John’s Aisle to the north of the north transept. The north transept originally had a tunnel-vaulted ceiling aligned with those in the crossing and aisles. The St John’s Chapel, added in 1395, extended north of the aisle line and featured a turnpike stair, which was later re-set in the Burn restoration of the 19th century. During this restoration, the north transept was heightened, and a clerestory and plaster vaulted ceiling were introduced. A screen by William Hay from 1881-83, featuring sculptures and the arms of William Chambers, now divides the transept, while a fragment of medieval blind tracery remains visible at its western end.

The south transept originally extended only to the line of the south aisles and was progressively expanded with the addition of the Preston, Chepman, and Holy Blood Aisles. The original barrel vault of the south transept is preserved, though it includes a later transverse arch supported by heavy corbels, likely added after the Preston Aisle’s construction. This arch supports an extension of the lower part of the tower and features a 15th-century traceried window. Like the north transept, the south transept was also heightened and fitted with a clerestory and plaster vaulted ceiling during William Burn’s restoration.

Choir and Choir Aisels

The Buildings of Scotland series describes the choir of St Giles’ as “the finest piece of late medieval parish church architecture in Scotland.” The choir was constructed in two main phases, with the initial phase in the 14th century and a significant extension in the 15th century. Archaeological evidence suggests that the choir was nearly completed in a single phase before the mid-15th century. Originally built as a hall church, the choir’s first three bays feature simple, octagonal pillars. By the middle of the 15th century, two additional bays were added to the eastern end, and the central section was elevated to include a clerestory and a tierceron-vaulted ceiling in stone. Remnants of the original vault’s springers are visible above the choir pillars, and the original roof’s outline is discernible above the eastern arch of the crossing. A grotesque at the ceiling’s central rib intersection with the tower’s east wall might be a remnant of the earlier 12th-century church.

During the 15th-century extension, the two new pillars added to the choir were decorated with heraldic arms. The northern pillar, known as the “King’s Pillar,” features the arms of James III, James II, Mary of Guelders, and France, dating the work to between 1453 and 1463. The southern pillar, or “Town’s Pillar,” displays the arms of various prominent individuals, including William Preston of Gorton and James Kennedy, Bishop of St Andrews. The south respond bears the arms of Thomas Cranstoun, Chief Magistrate of Edinburgh, while the north respond shows the arms of Alexander Napier of Merchiston, Provost of Edinburgh. Archaeological findings from the 1980s suggest that the choir’s expansion and the creation of the Preston Aisle might have been motivated by structural issues due to poor foundations, necessitating significant renovations.

The two choir aisles at St Giles’ Church differ significantly in size, with the north aisle being only two-thirds the width of the south aisle, which previously housed the Lady Chapel before the Reformation. Richard Fawcett proposes that both aisles were rebuilt after 1385. The design of both aisles features domed spandrels between the ribs, creating a visually striking effect. These ribs, while primarily structural, form pointed barrel vaults due to the lack of intersections between the lateral and longitudinal cells of each bay. The mid-15th century extension added proper lateral cells to the eastern bays of both aisles. Notable features include a 15th-century tomb recess in the north wall of the north choir aisle, where a re-set grotesque from the 12th-century church can be seen. A stone staircase added by Bernard Feilden and Simpson & Brown in 1981–82 is located at the east end of the south aisle.

Adjacent to the north choir aisle, the Chambers Aisle was constructed between 1889 and 1891 by MacGibbon and Ross as a memorial to William Chambers. This Aisle replaced a medieval vestry that had been converted to the Town Clerk’s office before its restoration by William Burn. MacGibbon and Ross integrated medieval masonry into the new arch and vaulted ceiling. To the south of the western three bays of the south choir aisle is the Preston Aisle, founded by William Preston of Gorton. Construction began in 1455, and although intended for completion within seven years, it appears to have extended well beyond that, as evidenced by the presence of Lord Hailes’ arms in the Aisle. The tierceron vault and pillars closely resemble those in the 15th-century choir extension. Extending further south from the Preston Aisle is the Chepman Aisle, established by Walter Chepman in 1507 and consecrated in 1513. Its pointed barrel vault features a central boss depicting an angel with Chepman’s arms and those of his first wife, Mariota Kerkettill. The Aisle was divided into three storeys during the Burn restoration and later restored in 1888 by Robert Rowand Anderson.

Stained Glass

St Giles’ is glazed with 19th and 20th century stained glass by a diverse array of artists and manufacturers. Between 2001 and 2005, the church’s stained glass was restored by the Stained Glass Design Partnership of Kilmaurs. Fragments of the medieval stained glass were discovered in the 1980s: none was obviously pictorial and some may have been grisaille. A pre-Reformation window depicting an elephant and the emblem of the Incorporation of Hammermen survived in the St Eloi Aisle until the 19th century. References to the removal of the stained glass windows after the Reformation are unclear. A scheme of coloured glass was considered as early as 1830: three decades before the first new coloured glass in a Church of Scotland building was installed at Greyfriars Kirk in 1857; however, the plan was rejected by the town council.

By the 1860s, Scottish Presbyterian attitudes towards stained glass had become more accepting, leading to a significant incorporation of new windows in St Giles’ Church as part of William Chambers’ restoration plan. James Ballantine & Son were commissioned to create a series of stained glass windows depicting the life of Christ, beginning with a 1874 window in the north choir aisle and culminating in the grand east window of 1877, illustrating the Crucifixion and Ascension. Other notable works by Ballantine & Son include the Prodigal Son window in the south nave aisle, the Albany Aisle’s west window with scenes from the parables, and the Preston Aisle’s west window featuring Saint Paul. They also created the unique Holy Blood Aisle window, which is the only one in the church depicting Scottish historical events. The subsequent firm, Ballantine & Gardiner, produced additional windows including those in the Preston Aisle and Chambers Aisle, portraying various biblical scenes. Edward Burne-Jones designed the Joshua window (1886) and a window showing Joshua and the Israelites (1886) in collaboration with Morris & Co., while Daniel Cottier’s east window in the north nave aisle represents Christian virtues. Victorian-era stained glass artists also include Burlison & Grylls and Charles Eamer Kempe, who created notable windows depicting biblical figures and writers.

Memorials

St. Giles’ houses over a hundred memorials, predominantly from the 19th century onwards. During the medieval period, the church floor was covered with memorial stones and brasses, many of which were removed after the Reformation. The Burn restoration of 1829–1833 led to the destruction of most post-Reformation memorials, with fragments relocated to Culter Mains and Swanston. William Chambers’ vision to transform St Giles’ into the “Westminster Abbey of Scotland” included installing memorials to notable Scots, overseen by a management board established in 1880, which managed new monuments until 2000. All the memorials were conserved between 2008 and 2009.

Ancient, Victorian, Edwardian Memorials

St. Giles’ hosts a diverse collection of memorials, primarily from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Surviving medieval tomb recesses are found in the Preston, Holy Blood, Albany Aisles, and the north choir aisle, with fragments of memorial stones re-incorporated into the Preston Aisle’s east wall. Among notable memorials, the brass plaque to the Regent Moray in the Holy Blood Aisle, originally part of a 1570 monument, was saved and reinstalled in 1864. Other significant plaques include those for John Stewart, 4th Earl of Atholl in the basement vestry and the Napiers of Merchiston on the north choir exterior wall. Victorian and Edwardian memorials, many installed between the Burn and Chambers restorations, are prominently displayed in the north transept. Key examples from this period include a plaque for Walter Chepman by Francis Skidmore (1879), a memorial to Jenny Geddes (1885), and large Jacobean-style monuments to James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose (1888) and Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll (1895). Prominent figures commemorated include Robert Louis Stevenson (1904) and John Knox, whose statue by James Pittendrigh MacGillivray (1906) was relocated from Parliament Square to its current place in the north nave aisle

20th & 21st century Memorials and Military Memorials

In St. Giles’, several modern memorials reflect notable figures and events from the 19th and 20th centuries. Designed by Robert Lorimer, memorials in the north choir aisle include a bronze plaque for Sophia Jex-Blake (1912) and a stone plaque for James Nicoll Ogilvie (1928), while Lorimer himself is commemorated by a 1932 plaque in the Preston Aisle, designed by Alexander Paterson. Relief portrait plaques in the Moray Aisle honor writers such as Robert Fergusson (1927) and Margaret Oliphant (1908), with sculptures by James Pittendrigh Macgillivray and Pilkington Jackson. Other modern sculptures include Merilyn Smith’s 1992 bronze of a stool commemorating Jenny Geddes and Kindersley Cardozo Workshop’s 1997 plaques for James Young Simpson and Ronald Colville, 2nd Baron Clydesmuir.

Military memorials are predominantly located at the west end of St. Giles’, with notable examples including John Steell’s 1850 memorial to the 78th (Highlanders) Regiment and William Brodie’s 1864 memorial for the 93rd (Sutherland Highlanders). The Royal Scots Greys’ Sudan memorial (1886) and various Second Boer War memorials, including those by John Rhind and the Rhind family, are also prominent. World War memorials include Henry Snell Gamley’s 1926 bronze relief for the congregation’s First World War memorial in the Albany Aisle, and Esmé Gordon’s 1951 tablets in the Albany Aisle for Second World War casualties. Notable Second World War memorials also include Basil Spence’s wooden plaque for the 94th (City of Edinburgh) Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment and the Church of Scotland chaplains memorial by Charles Henshaw.

Clock and Bells

The current clock was manufactured by James Ritchie & Son and installed in 1911; this replaced a clock of 1721 by Langley Bradley of London, which is now housed in the Museum of Edinburgh. A clock is recorded in 1491. Between 1585 and 1721, the former clock of Lindores Abbey was used in St Giles’.

The hour bell of the cathedral was cast in 1846 by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, possibly from the metal of the medieval Great Bell, which had been taken down about 1774. The Great Bell was cast in Flanders in 1460 by John and William Hoerhen and bore the arms of Guelderland and an image of the Virgin and Child. Robert Maxwell cast the second bell in 1706 and the third in 1728: these chime the quarters, the latter bears the coat of arms of Edinburgh. Between 1700 and 1890, a carillon of 23 bells, manufactured in 1698 and 1699 by John Meikle, hung in the tower. Daniel Defoe, who visited Edinburgh in 1727, praised the bells but added “they are heard much better at a distance than near at hand”. In 1955, an anonymous elder donated one of the carillon’s bells: it hangs in a Gothic wooden frame next to the Chambers Aisle. Nearby hangs the bell of HMS Howe: this was presented in 1955 by the Admiralty to mark the ship’s connection to Edinburgh. The bell hangs in a frame topped by a naval crown: this was made from Howe’s deck timbers. The vesper bell of 1464 stands in the south nave aisle.

Flags and heraldry

From 1883, regimental colours were displayed in the nave of St. Giles’, and in 1982, the Scottish Command of the British Army undertook to catalogue and preserve these colours, leading to their removal from the nave and the reinstatement of 29 in the Moray Aisle. Since 1953, the banners of the current knights of the Thistle have been exhibited in the Preston Aisle near the Thistle Chapel entrance, while the banner of Douglas Haig, donated by Lady Haig in 1928, is located in the Chambers Aisle. A large wooden panel depicting the arms of George II, painted by Roderick Chalmers in 1736, adorns the tower wall at the west end of the choir. Additionally, the Fetternear Banner, the sole surviving religious banner from pre-Reformation Scotland, made around 1520 for the Confraternity of the Holy Blood, and depicting the wounded Christ and the instruments of His Passion, is preserved by the National Museum of Scotland.

Chapels

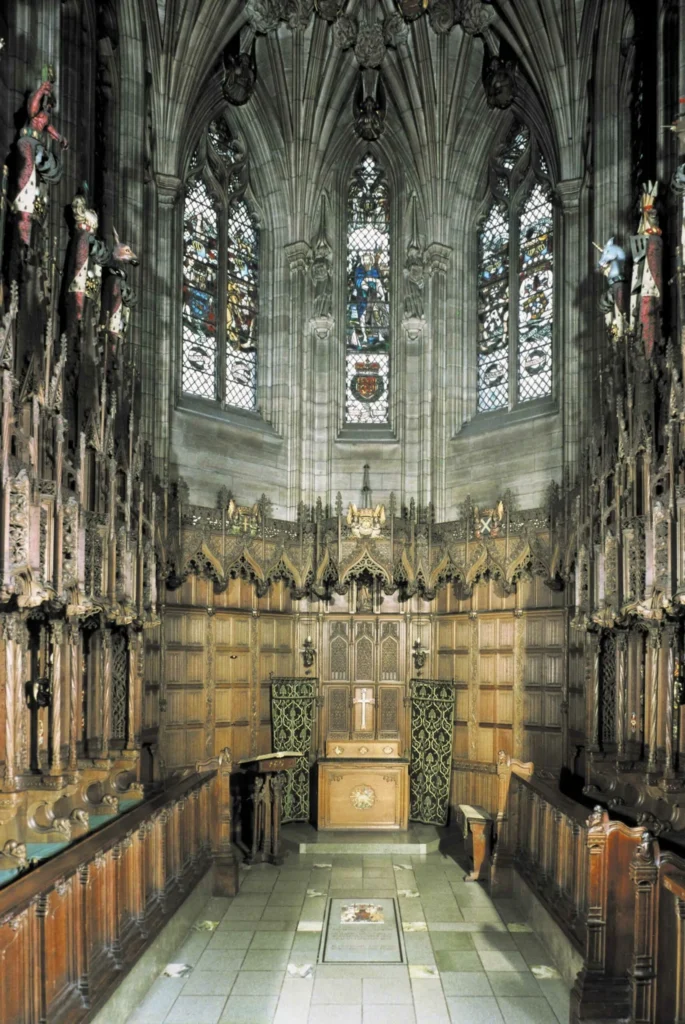

The Thistle Chapel, located at the south-east corner of St Giles’ Cathedral, serves as the chapel for the Order of the Thistle. It is accessed from the church’s south choir aisle and externally via the east door. Originally intended for Holyrood Abbey in 1687, the chapel was never used due to its destruction by a mob following James VII’s deposition. By the early 20th century, proposals to refurbish Holyrood Abbey or build a new chapel in St Giles’ emerged, culminating in the construction of the Thistle Chapel after a donation of £24,000 by Ronald Leslie-Melville, 11th Earl of Leven, in 1906. The King appointed Robert Lorimer as architect, who assembled a team from the Scottish Arts and Crafts movement, including Phoebe Anna Traquair, Douglas Strachan, and Joseph Hayes. Completed in 1911, the chapel is celebrated for its Gothic architecture and rich details, reflecting a blend of craftsmanship and Scottish patriotism. The chapel remains a site of significance for the Order of the Thistle, where new knights are inducted and the tradition of craftsmanship continues.

Pipe Organ

The pipe organ was completed in 1992 and is located in the south transept: it was made by Rieger Orgelbau and donated by Alastair Salvesen. Douglas Laird designed the case: it imitates the prow of a ship and uses red-stained Austrian oak along with decorative bronze and glass features. The organ has 4,156 pipes, most of which are tin. The Glocken is a ring of 37 bells made by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry.

The current organ replaced a Harrison & Harrison organ of 1878, the first organ in the church since the Reformation. This organ initially possessed 2 manuals and 26 stops. Between 1872 and this organ’s installation, a harmonium was used in services. Harrison & Harrison rebuilt the organ in 1883 and 1887. Eustace Ingram rebuilt the organ as a 4 manual, 60 stop instrument in 1895. Ingram & Co rebuilt the organ in 1909 and overhauled it between 1936 and 1939. The organ was reconstructed in 1940 by Henry Willis & Sons as a 4 manual, 74 stop instrument with a new console and an extra console in the Moray Aisle; a new case was designed by Esmé Gordon: this incorporated statues of angels and Jubal by Elizabeth Dempster. The second console was removed in 1980 and Willis overhauled the organ in 1982. The organ was removed in 1990, some of the pipes were removed to the McEwan Hall, Peebles Old Parish Church, and the Scottish Theatre Organ Preservation Trust; two were incorporated in the replacement organ; the console was donated to a church in Perth.

Feast Day

Feast day: 1st September

St. Giles’ devotion spread widely across Europe during the Middle Ages, as evidenced by the numerous churches and monasteries dedicated to him throughout the continent. His feast day is celebrated on September 1st.

Mass Timing

Sunday mornings: Holy Communion at 9.30am and Morning Worship at 11am

Church Opening Hours

Sunday 1 pm – 5 pm,

Saturday 9 am – 5 pm,

Weekdays 10 am – 6 pm

Contact Info

Address:

St. Giles Cathedral

2-4 High Steet, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Phone : +44 131 226 0674

Accommodations

Connectivities

Airway

Edinburgh Airport (EDI) to St Giles’ Cathedral distance 13.2 km(35mins).

Railway

Edinburgh station to St. Giles cathedral distance 27 min (9.5 mins) via The City of Edinburgh Bypass/A720 and Colinton Rd