Introduction

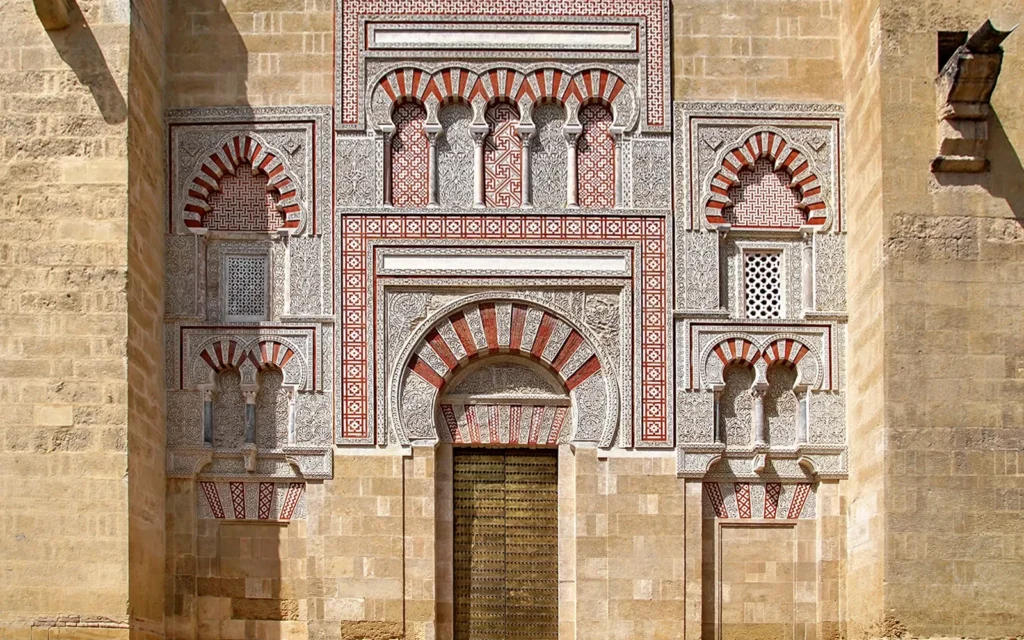

The Mosque-Cathedral of Cordoba (World Heritage Site since 1984) is arguably the most significant monument in the whole of the western Moslem World and one of the most amazing buildings in the world in its own right. The complete evolution of the Omeyan style in Spain can be seen in its different sections, as well as the Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque styles of the Christian part.

The Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba (Spanish: Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba), officially known by its ecclesiastical name of Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption (Spanish: Catedral de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción), is the cathedral of the Diocese of Córdoba dedicated to the Assumption of Mary and located in the Spanish region of Andalusia. Due to its status as a former mosque, it is also known as the Mezquita; ‘mosque’ in Spanish) and as the Great Mosque of Córdoba.

According to traditional accounts a Visigothic church, the Catholic Christian Basilica of Vincent of Saragossa, originally stood on the site of the current Mosque-Cathedral, although this has been a matter of scholarly debate. The Great Mosque was constructed in 785 on the orders of Abd al-Rahman I, founder of the Islamic Emirate of Córdoba. It was expanded multiple times afterwards under Abd al-Rahman’s successors up to the late 10th century. Among the most notable additions, Abd al-Rahman III added a minaret (finished in 958) and his son al-Hakam II added a richly-decorated new mihrab and maqsurah section (finished in 971). The mosque was converted to a cathedral in 1236 when Córdoba was captured by the Christian forces of Castile during the Reconquista.

The structure itself underwent only minor modifications until a major building project in the 16th century inserted a new Renaissance cathedral nave and transept into the center of the building. The former minaret, which had been converted to a bell tower, was also significantly remodelled around this time. Starting in the 19th century, modern restorations have in turn led to the recovery and study of some of the building’s Islamic-era elements. Today, the building continues to serve as the city’s cathedral and Mass is celebrated there daily.

The mosque structure is an important monument in the history of Islamic architecture and was highly influential on the subsequent “Moorish” architecture of the western Mediterranean regions of the Muslim world. It is also one of Spain’s major historic monuments and tourist attractions, as well as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1984.

A claim that the site of the mosque-cathedral was once a Roman temple dedicated to Janus dates as far back as Pablo de Céspedes and is sometimes still repeated today. However, Robert Knapp, in his overview of Roman-era Córdoba, has dismissed this claim as speculation based on a misunderstanding of Roman milestones found in the area.

Visigothic church

According to traditional accounts, the present-day site of the Cathedral–Mosque of Córdoba was originally a Visigothic Christian church dedicated to Saint Vincent of Saragossa, which was divided and shared by Christians and Muslims after the Umayyad conquest of Hispania. As the Muslim community grew and this existing space became too small for prayer, the basilica was expanded little by little through piecemeal additions to the building. This sharing arrangement of the site lasted until 785, when the Christian half was purchased by Abd al-Rahman I, who then proceeded to demolish the church structure and build the grand mosque of Córdoba on its site. In return, Abd al-Rahman also allowed the Christians to rebuild other ruined churches – including churches dedicated to the Christian martyrs Saints Faustus, Januarius, and Marcellus whom they deeply revered – as agreed upon in the sale terms

The historicity of this narrative has been challenged as archaeological evidence is scant and the narrative is not corroborated by contemporary accounts of the events following Abd al-Rahman I’s initial arrival in al-Andalus. The narrative of the church being transformed into a mosque, which goes back to the tenth-century historian Al-Razi, echoed similar narratives of the Islamic conquest of Syria, in particular the story of building the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. For medieval Muslim historians, these parallels served to highlight a dynastic Umayyad conquest of Spain and appropriation of Visigothic Córdoba. Another tenth-century source mentions a church that stood at the site of the mosque without giving further details. An archaeological exhibit in the mosque–cathedral of Cordoba today displays fragments of a Late Roman or Visigothic building, emphasizing an originally Christian nature of the complex. The “stratigraphy” of the site is complicated and made more so by its impact on contemporary political debates about cultural identity in Spain

According to Susana Calvo Capilla, a specialist on the history of the mosque–cathedral, although remains of multiple church-like buildings have been located on the territory of the mosque–cathedral complex, no clear archaeological evidence has been found of where either the church of St. Vincent or the first mosque were located on the site, and the latter may have been a newly constructed building. The evidence suggests that it may have been the grounds of an episcopal complex rather than a particular church which were initially divided between Muslims and Christians. Pedro Marfil, an archeologist at the University of Cordoba, has argued for the existence of such a complex – including a Christian basilica – on this site by interpreting the existing archeological remains. D. Fairchild Ruggles, a scholar of Islamic art, considers previous archeological work to be a confirmation of the former church’s existence. This theory has been opposed by Fernando Arce-Sainz, another archeologist, who states that none of the numerous archeological investigations in modern times have turned up remains of Christian iconography, a cemetery, or other evidence that would support the existence of a church. Art historian Rose Walker, in an overview of late antique and early medieval art in Spain, has likewise criticized Marfil’s view as relying on personal interpretation. More recently, archeologists Alberto León and Raimundo Ortiz Urbano have affirmed the hypothesis of a large episcopal complex by analyzing both old and new archeological findings at the site, while María de los Ángeles Utrero Agudo and Alejandro Villa del Castillo argue that evidence so far does not allow for the identification of former ecclesiastical structures on the site.

Regardless of what structures may have existed on the site, however, it is almost certain that the building which housed the city’s first mosque was destroyed to build Abd ar-Rahman I’s Great Mosque and that it had little relation to the latter’s form.

Architecture of the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba, Spain

The Great Mosque was built in the context of the new Umayyad Emirate in Al-Andalus which Abd ar-Rahman I founded in 756. Abd ar-Rahman was a fugitive and one of the last remaining members of the Umayyad royal family which had previously ruled the first hereditary caliphate based in Damascus, Syria. This Umayyad Caliphate was overthrown during the Abbasid Revolution in 750 and the ruling family were nearly all killed or executed in the process. Abd ar-Rahman survived by fleeing to North Africa and, after securing political and military support, took control of the Muslim administration in the Iberian Peninsula from its governor, Yusuf ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Fihri. Cordoba was already the capital of the Muslim province and Abd ar-Rahman continued to use it as the capital of his independent emirate.

Construction of the mosque began in 785–786 (169 AH) and finished a year later in 786–787 This relatively short period of construction was aided by the reuse of existing Roman and Visigothic materials in the area, especially columns and capitals. Syrian (Umayyad), Visigothic, and Roman influences have been noted in the building’s design, but the architect is not known. The craftsmen working on the project probably included local Iberians as well as people of Syrian origin. According to tradition and historical written sources, Abd ar-Rahman involved himself personally and heavily in the project, but the extent of his personal influence in the mosque’s design is debated.

Original layout

The original mosque had a roughly square floor plan measuring 74 or 79 square meters per side, equally divided between a hypostyle prayer hall to the south and an open courtyard (sahn) to the north. As the mosque was built on a sloping site, a large amount of fill would have been necessary to create a level ground on which to build. The outer walls were reinforced with large buttresses, which are still visible on the exterior today. The original mosque’s most famous architectural innovation, which was preserved and repeated in all subsequent Muslim-era expansions, was its rows of two-tiered arches in the hypostyle hall.

The mosque’s original mihrab (niche in the far wall symbolizing the direction of prayer) no longer exists today but its probable remains were found during archeological excavations between 1932 and 1936. The remains showed that the mihrab’s upper part was covered with a shell-shaped hood similar to the later mihrab.

The mosque originally had four entrances: one was in the center of the north wall of the courtyard (aligned with the mihrab to the south), two more were in the west and east walls of the courtyard, and a fourth one was in the middle of the west wall of the prayer hall. The latter was known as Bab al-Wuzara’ (the “Viziers’ Gate”, today known as Puerta de San Esteban) and was most likely the entrance used by the emir and state officials who worked in the palace directly across the street from here.

The courtyard of the mosque was planted with trees as early as the 9th century, according to written sources cited by the 11th century jurist Ibn Sahl. Although the species of tree is not known, the fact that these were fruit trees is attested in Ibn Sahl, who was consulted as to whether such a garden was forbidden and, if not forbidden, whether it was permitted to eat from it. That the trees remained in the courtyard is demonstrated by two seals of the City of Cordoba, one in 1262 and the other in 1445, both of which show the mosque (which by then had been converted to a cathedral) within whose walls appear tall palm trees. This evidences makes the Cordoba mosque the earliest one where trees are known to have been planted in the courtyard.

Later Islamic history of the mosque (11th–12th centuries)

After the collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate in Cordoba at the beginning of the 11th century, no further expansions to the mosque were carried out. Indeed, the collapse of authority had immediate negative consequences for the mosque, which was looted and damaged during the fitna (civil conflict) that followed the caliphate’s fall (roughly between 1009 and 1030). Cordoba itself also suffered a decline but remained an important cultural center. Under Almoravid rule, the artisan workshops of Cordoba were commissioned to design new richly-crafted minbars for the most important mosques of Morocco – most famously the Minbar of the Kutubiyya Mosque commissioned in 1137 – which were likely inspired by the model of al-Hakam II’s minbar in the Great Mosque.

In 1146 the Christian army of King Alfonso VII of León and Castile briefly occupied Cordoba. The archbishop of Toledo, Raymond de Sauvetât, accompanied by the king, led a mass inside the mosque to “consecrate” the building. According to Muslim sources, before leaving the city the Christians plundered the mosque, carrying off its chandeliers, the gold and silver finial of the minaret, and parts of the rich minbar. As a result of both this pillage and the earlier pillage during the fitna, the mosque had lost almost all of its valuable furnishings.

In 1162, after a general period of decline and recurring sieges, the Almohad caliph Abd al-Mu’min ordered that Cordoba be prepared to become his capital in al-Andalus. As part of this preparation, his two sons and governors, Abu Yaqub Yusuf and Abu Sa’id, ordered that the city and its monuments be restored. The architect Ahmad ibn Baso (who was later known for his work on the Great Mosque of Seville) was responsible for carrying out this restoration program. It is not known exactly which buildings he restored, but it is almost certain that he restored the Great Mosque. It is likely that the mosque’s minbar was also restored at this time, since it is known to have survived long afterwards up to the 16th century.

Reconquista and conversion to cathedral (13th century)

In 1236 Córdoba was conquered by King Ferdinand III of Castile as part of the Reconquista. Upon the city’s conquest the mosque was converted into a Catholic cathedral dedicated to the Virgin Mary (Santa Maria). The first mass was dedicated here on June 29 of that year. According to Jiménez de Rada, Ferdinand III also carried out the symbolic act of returning the former cathedral bells of Santiago de Compostela that were looted by Al-Mansur (and which had been turned into mosque lamps) back to Santiago de Compostela.

Despite the conversion, the early Christian history of the building saw only minor alterations being done to its structure, mostly limited to the creation of small chapels and the addition of new Christian tombs and furnishings. Even the mosque’s minbar was apparently preserved in its original storage chamber, though it is unknown if it was used in any way during this time. (The minbar has since disappeared, but it still existed in the 16th century, when it was apparently seen by Ambrosio de Morales.)

The cathedral’s first altar was installed in 1236 under the large ribbed dome at the edge of Al-Hakam II’s 10th-century extension of the mosque, becoming part of what is today called the Villaviciosa Chapel (Capilla de Villaviciosa) and the cathedral’s first main chapel (the Antigua Capilla Mayor). There is no indication that even this space was significantly modified in its structure at this time. The area of the mosque’s mihrab and maqsura, along the south wall, was converted into the Chapel of San Pedro and was reportedly where the host was stored. What is today the 17th-century Chapel of the Conception (Capilla de Nuestra Señora de la Concepción), located on the west wall near the courtyard, was initially the baptistery in the 13th century. These three areas appear to have been the most important focal points of Christian activity in the early cathedral. The minaret of the mosque was also converted directly into a bell tower for the cathedral, with only cosmetic alterations such as the placement of a cross at its summit.

Notably, during the early period of the cathedral-mosque, the workers charged with maintaining the building (which had suffered from disrepair in previous years) were local Muslims (Mudéjars). Some of them were kept on payroll by the church but many of them worked as part of their fulfilment of a “labor tax” on Muslim craftsmen (later extended to Muslims of all professions) which required them to work two days a year on the cathedral building. This tax was imposed by the crown and was unique to the city of Cordoba. It was probably instituted not only to make use of Mudéjar expertise but also to make up for the cathedral chapter’s relative poverty, especially vis-à-vis the monumental task of repairing and maintaining such a large building. At the time, Mudéjar craftsmen and carpenters were especially valued across the region and even held monopolies in some Castilian cities such as Burgos.

Other chapels were progressively created around the interior periphery of the building over the following centuries, many of them funerary chapels built through private patronage. The first precisely-dated chapel known to be built along the west wall is the Chapel of San Felipe and Santiago, in 1258. The Chapel of San Clemente was created in the southeast part of the mosque before 1262. A couple of early Christian features, such as an altar dedicated to San Blas (installed in 1252) and an altar of San Miguel (1255), disappeared in later centuries

Mosque–Cathedral 14th–15th centuries

The Royal Chapel was constructed in a lavish Mudéjar style with a ribbed dome very similar to the neighbouring dome of the Villaviciosa Chapel and with surfaces covered in carved stucco decoration typical of Nasrid architecture at the time. This prominent use of the Moorish-Mudéjar style for a royal funerary chapel (along with other examples like the Mudéjar Alcázar of Seville) is interpreted by modern scholars as a desire by the Christian kings to appropriate the prestige of Moorish architecture in the Iberian Peninsula, just as the Mosque of Cordoba was itself a powerful symbol of the former Umayyad Caliphate’s political and cultural power which the Castilians were eager to appropriate.

Modern Reconstruction 19th–21st centuries

In 1816 the original mihrab of the mosque was uncovered from behind the former altar of the old Chapel of San Pedro. Patricio Furriel was responsible for restoring the mihrab’s Islamic mosaics, including the portions which had been lost. Further restoration works concentrating on the former mosque structure were carried out between 1879 and 1923 under the direction of Velázquez Bosco, who among other things dismantled the baroque elements that had been added to the Villaviciosa Chapel and uncovered the earlier structures there. During this period, in 1882, the cathedral and mosque structure was declared a National Monument. Further research work and archaeological excavations were carried out on the mosque structure and in the Courtyard of the Oranges by Félix Hernández between 1931 and 1936. More recent scholars have noted that modern restorations since the 19th century have partly focused on “re-islamicizing” (in architectural terms) parts of the Mosque-Cathedral. This took place in the context of wider conservation efforts in Spain, starting in the 19th century, towards studying and restoring Islamic-era structures.

The Mosque-Cathedral was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1984, and in 1994 this status was extended to the entire historic centre of Cordoba. A restoration project began on the bell tower in 1991 and finished in 2014, while the transept and choir of the Renaissance cathedral were also restored between 2006 and 2009. Further restorations of features like chapels and some of the outer gates have continued to take place up to the late 2010s

The Christian-era additions (after 1236) included many small chapels throughout the building and various relatively cosmetic changes. The most substantial and visible additions are the cruciform nave and transept of the Capilla Mayor (the main chapel where Mass is held today) which were begun in the 16th century and inserted into the middle of the former mosque’s prayer hall, as well as the remodelling of the former minaret into a Renaissance-style bell tower.

Construction of a new cathedral bell tower to encase the old minaret began in 1593 and, after some delays, was finished in 1617 It was designed by architect Hernan Ruiz III (grandson of Hernan Ruiz I), who built the tower up to the bell’s level but died before its completion. His plans were followed and completed by Juan Sequero de Matilla.The bell tower is 54 meters tall and is the tallest structure in the city. It consists of a solid square shaft up to the level of the bells, where serliana-style openings feature on all four sides. Above this is a lantern structure which in turn is surmounted by a cupola. The dome at the summit is topped by a sculpture of Saint Raphael which was added in 1664 by architect Gaspar de la Peña, who had been hired to perform other repairs and fix structural problems. The sculpture was made by Pedro de la Paz and Bernabé Gómez del Río. Next to the base of the tower is the Puerta del Perdón (“Door of Forgiveness”), one of the two northern gates of the building.

Main Altar

The altar of the Capilla Mayor was begun in 1618 and designed in a Mannerist style by Alonso Matías. After 1627 the works were taken over by Juan de Aranda Salazar, and the altar was finished in 1653. The sculpting was executed by the artists Sebastián Vidal and Pedro Freile de Guevara. The original paintings of the altar were executed by Cristóbal Vela Cobo but they were replaced in 1715 by the current paintings by Antonio Palomino. The altar consists of three vertical “aisles” flanked by columns with composite capitals. The central aisle houses the tabernacle (executed by Pedro Freile de Guevara) at its base, while its upper half is occupied by a canvas of the Assumption. The two aisles on the side contain four more canvases depicting four martyrs: Saint Acisclus and Saint Victoria on the bottom halves and Saint Pelagius and Saint Flora in the upper halves. The upper canvases are flanked by sculptures of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, and the central portion is topped by a relief sculpture of God the Father

Choir Stalls

The choir stalls, located across from the altar, were crafted from 1748 to 1757 and were executed by Pedro Duque Cornejo. The ensemble was carved mainly out of mahogany wood and features a row of 30 upper seats and a row of 23 lower seats, all intricately decorated with carvings, including a series of iconographic scenes. At the centre of the ensemble on the west side is a large episcopal throne, commissioned in 1752, that resembles the design of an altarpiece. The lower part of the thrones has three seats, but the most significant element is the upper part which features a life-size representation of the Ascension of Jesus. The last figure which stands above the summit of the ensemble is a sculpture of the Archangel Raphael.

Feast Day

There is no Particular Feast Day

Church Opening Time

November-February :

Monday to Saturday

8:30 am – 06:00 pm

Sundays and religious holidays,

8:30 am – 11:30 pm

March-October :

Monday to Saturday,

10.00 am-07:00 pm

Sundays and religious holidays,

8:30-11:30 am.

Mass Timing

Monday to Friday: Coro Catedralicio at 9:30am

Sunday & Festivals: Altar Mayor- Solemn Mass at 12pm; and 1:30pm

Contact Info

Address

Centro, 14003 Córdoba, Spain

Phone :+34 957 47 05 12

Accommodations

Connectivities

Airway

Cordoba Airport to Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba Spain Distance 17 min (7.9 km) via N-437

Railway

Cordoba Train Station to Mosque-Cathedral of Cordoba Spain Distance 8 min (2.0 km) via A-431