Introduction

The Church of the Nativity, or Basilica of the Nativity, is a basilica located in Bethlehem in the State of Palestine, in the West Bank. The grotto holds a prominent religious significance to Christians of various denominations as the birthplace of Jesus. The grotto is the oldest site continuously used as a place of worship in Christianity, and the basilica is the oldest major church in the Holy Land. The church was first built under Constantine the Great shortly after his mother Helena’s journey to Jerusalem and Bethlehem in 325–326, at the location traditionally believed to be Jesus’s birthplace. The original basilica, probably constructed between 330 and 333, was mentioned as early as 333 and was consecrated on May 31, 339. It likely suffered damage from fires during Samaritan uprisings in the sixth century, perhaps around 529. Byzantine Emperor Justinian (r. 527–565) later erected a new basilica, likely adding a porch and transforming the octagonal sanctuary into a cruciform transept with three apses. Despite modifications, the essence of the original structure, including an atrium and a basilica with a nave and four side aisles, was preserved.

Although the Church of the Nativity has retained its basic form since Justinian’s renovations, it has undergone several repairs and enhancements over time, particularly during the Crusades. These include the addition of two bell towers (now absent) and the installation of wall mosaics and paintings, some of which remain today. The surrounding complex has expanded over the centuries and now encompasses around 12,000 square meters, housing three distinct monasteries: Catholic, Armenian Apostolic, and Greek Orthodox. The Catholic and Armenian monasteries feature modern-era bell towers.

In October 1847, Greek monks stole the silver star marking the spot of Christ’s birth, engraved in Latin, sparking controversy. Some argue that this event influenced the Crimean War against the Russian Empire, while others attribute the conflict to broader European tensions.

Designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2012, the Church of the Nativity was the first site listed under ‘Palestine’. Since 1852, the rights of the three religious communities have been governed by the Status Quo.

Of the four canonical gospels, Matthew and Luke mention the birth of Jesus, both placing it in Bethlehem. Luke mentions the manger: “and she gave birth to her firstborn, a son. She wrapped him in cloths and placed him in a manger, because there was no guest room available for them.”

A variant of the narrative is contained in the Gospel of James, an apocryphal infancy gospel.

The Nativity Grotto, believed to be the cave of Jesus’s birth, has a significant history. In 135, Emperor Hadrian repurposed the site above the grotto as a shrine for Adonis, the mortal lover of Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of beauty and desire. Jerome, writing in 420, asserted that the grotto had been dedicated to Adonis worship, with efforts made to erase Jesus’s memory by planting a sacred grove there. Around AD 248, Greek philosopher Origen of Alexandria wrote about the grotto, confirming it as the place of Jesus’s birth, where He was laid in a manger. This knowledge is widely acknowledged among Christians and foreigners of the Faith, affirming Jesus’s significance in the Christian tradition.

Constantinian Basilica (326 – 529 or 556)

The first basilica at this location was erected by Emperor Constantine I, based on the site identified by his mother, Empress Helena, and Bishop Makarios of Jerusalem. Construction commenced in 326 under the supervision of Makarios, who followed Constantine’s directives, and was consecrated on May 31, 339. However, it had already been visited in 333 by the Bordeaux Pilgrim, indicating its prior use.

This early church’s construction was part of a broader initiative initiated during Constantine’s reign following the First Council of Nicaea. The aim was to construct churches at locations believed to be associated with significant events in Jesus’s life. The basilica’s design featured three main architectural elements:

- An apse at the eastern end, shaped in a polygonal form (a broken pentagon, instead of the previously suggested, but unlikely full octagon), enclosing a raised platform with an approximately 4-meter diameter opening in its floor, providing a direct view of the Nativity site below. Surrounding the apse was an ambulatory with adjacent rooms.

- A five-aisled basilica extending from the eastern apse, one bay shorter than the still-standing Justinianic reconstruction.

- A porticoed atrium.

The structure met its demise during one of the Samaritan Revolts, likely in 529 or 556, with indications that Jews may have participated alongside the Samaritans in the second revolt.

Justinian’s Basilica (6th Century)

The basilica underwent reconstruction in its current form during the 6th century, initiated by Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (527–565) following its destruction in either 529 or 556. It is believed that the reconstruction took place after the Emperor’s death, as suggested by the dating of wooden elements found in the church walls between 545 and 665, determined through dendrochronological analyses conducted during recent restoration efforts.

In 614, Palestine was invaded by the Persians under Khosrau II, who also captured Jerusalem nearby. However, they refrained from destroying the structure. According to legend, their commander Shahrbaraz was moved by the depiction above the church entrance of the Three Magi dressed as Persian Zoroastrian priests, prompting him to order the preservation of the building.

Crusader Period (1099-1187)

The Church of the Nativity served as the main coronation venue for Crusader kings, beginning with the second ruler of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1100 until 1131. Around 1130, during an earlier period, the Crusaders initiated the refurbishment of the building through wall paintings. Saints’ images adorned the central and southern colonnades of the nave, largely funded by private donors, evident from dedicatory inscriptions and portraits. Fragments of narrative scenes are visible in the north-western pillar of the choir, the south transepts, and the chapel beneath the bell tower. The Crusaders embarked on extensive decoration and restoration of the basilica and its surroundings, a process extending until 1169. From 1165 to 1169, there was even a collaborative effort involving the Latin Bishop of Bethlehem, Raoul, the Latin King Amalric I of Jerusalem, and the Byzantine emperor Manuel I Komnenos, as depicted in a bilingual Greek and Latin inscription in the altar area. The mosaic decoration was led by a painter named Ephraim, as indicated. Additionally, a bilingual Latin and Syriac inscription on a mosaic panel featuring an angel on the northern nave wall attests to the work of Basil, likely a local Syrian Melkite painter. Both artists collaborated within the same workshop.

Ayyubid and Mamluk Periods (1187-1516)

The Ayyubid conquest of Jerusalem and its surroundings in 1187 did not affect the Nativity church. The Greek-Melkite clergy were granted permission to serve in the church, with similar concessions extended almost immediately to other Christian denominations.

In 1227, the church received an ornate wooden door, remnants of which can still be observed in the narthex. Crafted by two Armenian monks, Father Abraham and Father Arakel, during the reign of King Hethum I of Cilicia (1224-1269) and the Emir of Damascus, and Saladin’s nephew, al-Mu’azzam Isa, the door bears a double inscription in Armenian and Arabic. In 1229, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II reached an agreement with Sultan al-Kamil, resulting in the restoration of the Holy Places to the Crusaders. The Nativity Church returned to the ownership of the Latin clergy under the condition that Muslim pilgrims could visit the holy cave. Latin control likely persisted until the invasion of Khwarezmian Turks in April 1244, during which the church treasures were concealed underground and later rediscovered in 1863, now housed in the Terra Sancta Museum in Jerusalem. While the church suffered significant damage, including roof deterioration, it was not completely destroyed.

During Mamluk rule, the church was utilized by various Christian denominations, including Greeks, Armenians, Copts, Ethiopians, and Syrians. In 1347, the Franciscans of the newly established Custody of the Holy Land were granted ownership of the former monastery north of the basilica, leading them to establish a significant presence in Bethlehem until the Ottoman era.

From the late 13th century, pilgrims noted the decay of the church interior by Mamluk authorities’ orders, particularly the removal of marble revetments from the walls and floors.

The Duchy of Burgundy undertook roof restoration efforts in August 1448, with contributions from multiple regions in 1480: England supplied lead, the Second Kingdom of Burgundy provided wood, and the Republic of Venice offered labor.

Ottoman Period, First Three Centuries (16th–18th)

Between 1834 and 1837, earthquakes caused considerable damage to the Church of the Nativity. The 1834 Jerusalem earthquake affected the church’s bell tower, the cave furnishings beneath the church, and other structural components. Subsequent strong aftershocks in 1836 and the Galilee earthquake of 1837 inflicted minor damages. In 1842, as part of repair efforts led by the Greek Orthodox following an official decree, a wall was erected between the nave and aisles, previously utilized as a market, and the eastern section housing the choir, enabling worship to continue in that area.

In October 1847, the Greek Orthodox removed the religiously significant silver star marking the exact birthplace of Jesus from the Grotto of the Nativity. Although the church was under Ottoman Empire control, Napoleon III compelled the Ottomans around Christmas 1852 to recognize Catholic France as the “sovereign authority” over Christian holy sites in the Holy Land. In response, the Sultan of Turkey reinstated the silver star at the grotto, featuring a Latin inscription. However, the Christian Orthodox Russian Empire disputed the change in authority, invoking the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca and deploying armies to the Danube area. Consequently, the Ottomans issued decrees essentially reversing their earlier decision, disavowing the French treaty, and reinstating Orthodox Christians as the sovereign authority over the Holy Land churches, thus exacerbating local tensions and escalating the conflict between the Russian and Ottoman empires for control over holy sites in the region.

Nineteenth Century

Between 1834 and 1837, earthquakes caused significant damage to the Church of the Nativity. The 1834 Jerusalem earthquake resulted in harm to the church’s bell tower, furnishings within the cave where the church stands, and other structural elements. Subsequent strong aftershocks in 1836 and the Galilee earthquake of 1837 caused additional minor damages. In 1842, the Greek Orthodox commenced repairs, constructing a wall between the nave and aisles, which were being used as a market at the time. This renovation also addressed the eastern section of the church, including the choir area, allowing worship to continue.

In October 1847, the Greek Orthodox removed the religiously significant silver star from the Grotto of the Nativity. Despite the church’s Ottoman Empire control, Napoleon III compelled recognition of Catholic France as the “sovereign authority” over Christian holy sites by the Ottomans around Christmas 1852. Consequently, the Sultan of Turkey reinstated the silver star at the grotto, bearing a Latin inscription. However, this change was disputed by the Christian Orthodox Russian Empire, invoking the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca and deploying armies to the Danube area. In response, the Ottomans reversed their decision, renouncing the French treaty, and restoring sovereign authority over the Holy Land churches to the Orthodox Christians. This action intensified tensions and fueled conflict between the Russian and Ottoman empires over control of holy sites in the region.

In 1918, British governor Colonel Ronald Storrs removed the wall that had been erected in 1842 by the Greek Orthodox between the nave and choir.

The passageway linking St. Jerome’s Cave and the Cave of the Nativity underwent expansion in February 1964 to facilitate easier access for visitors. American businessman Stanley Slotkin, visiting at the time, acquired a significant quantity of limestone rubble, consisting of over a million irregular fragments approximately 5 mm (0.20 in) in size. Slotkin then sold these fragments encased in plastic crosses, which were later advertised in infomercials in 1995.

During the Second Intifada in April 2002, the church became the focal point of a month-long siege, during which around 50 armed Palestinians sought refuge inside the church to evade the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). Christians within the church provided sanctuary to the fighters, offering them sustenance, shelter, and protection from the Israeli military forces stationed outside. While Israeli media asserted that the Christians inside were being held hostage, parishioners within the church maintained that they and the church were treated respectfully.

On May 27, 2014, curtains in the grotto beneath the church caught fire, resulting in minor damage.

Beginning in September 2013, the church’s co-owners initiated a significant renovation project, expected to be completed by 2021.

World Heritage Site

In 2012, the church complex achieved the distinction of becoming the first Palestinian site to be designated as a World Heritage Site by the World Heritage Committee during its 36th session on June 29. The decision was made through a secret vote, resulting in a 13–6 approval within the 21-member committee, as reported by UNESCO spokeswoman Sue Williams. This approval came after an emergency candidacy process, bypassing the typical 18-month procedure for most sites, despite objections from the United States and Israel. The site met the criteria for designation under both criteria four and six. However, the decision sparked controversy, both technically and politically. Initially, it was listed on the List of World Heritage in Danger from 2012 to 2019 due to damage caused by water leaks.

Restoration (2013–2019) Endangered Status

The basilica was included in the 2008 Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites by the World Monuments Fund.

The current condition of the church is cause for concern. Numerous roof timbers are decaying and have remained unchanged since the 19th century. Rainwater infiltration not only hastens the deterioration of the wood and compromises the building’s structural stability but also harms the 12th-century wall mosaics and paintings. The presence of water also heightens the risk of electrical fires. Should another earthquake occur on the scale of the 1834 one, the consequences would likely be disastrous. The listing aims to promote preservation efforts, including fostering collaboration among the church’s three custodians—the Greek Orthodox Church, the Armenian Orthodox Church, and the Franciscan order—something that has not occurred in centuries. Additionally, it calls for cooperation between the Israeli government and the Palestinian Authority to ensure the church’s protection.

In 2008, a Presidential committee was established for the restoration of the Nativity Church. The following year, an international consortium of experts from various universities, led by Prof. Claudio Alessandri from the University of Ferrara, Italy, was tasked with planning and overseeing the restoration efforts.

Logistics and Organisation

In 2010, the Palestinian Authority revealed plans for a multimillion-dollar restoration program. Despite being predominantly Muslim, with a notable Christian minority, Palestinians view the church as a national treasure and one of their most frequented tourist destinations. President Mahmoud Abbas has taken an active role in the initiative, which is overseen by Ziad al-Bandak. The project receives partial funding from Palestinians and involves collaboration between Palestinian and international experts.

Restoration Process

The first stage of the restoration project concluded in early 2016. During this phase, new windows were fitted, repairs were made to the roof’s structure, and artworks and mosaics underwent cleaning and restoration. The project progressed to include the reinforcement of the narthex, the cleaning and strengthening of all wooden components, as well as the restoration of wall mosaics, mural paintings, and floor mosaics. The restoration efforts concluded in 2020

Discoveries

In July 2016, Italian restoration workers made a discovery of a seventh surviving mosaic angel that had been concealed under plaster. Marcello Piacenti, the Italian restorer, described the mosaics as being crafted with gold leaf placed between two glass plates. He noted that only the faces and limbs are depicted using small pieces of stone.

Property and Administration

The governance of the church, including property rights, liturgical practices, and maintenance, is governed by a collection of agreements and documents referred to as the Status Quo. Ownership of the church is divided among three church authorities: the Greek Orthodox (with primary ownership of the building and furnishings), the Catholic, and the Armenian Apostolic (each with varying degrees of ownership). Additionally, the Coptic Orthodox and Syriac Orthodox hold minor worship rights at the Armenian church in the northern transept and at the Altar of Nativity. Incidents of conflict among monk trainees regarding the observance of others’ prayers, hymns, and the allocation of floor space for cleaning responsibilities have occurred repeatedly. As a result, Palestinian police are frequently summoned to restore peace and order.

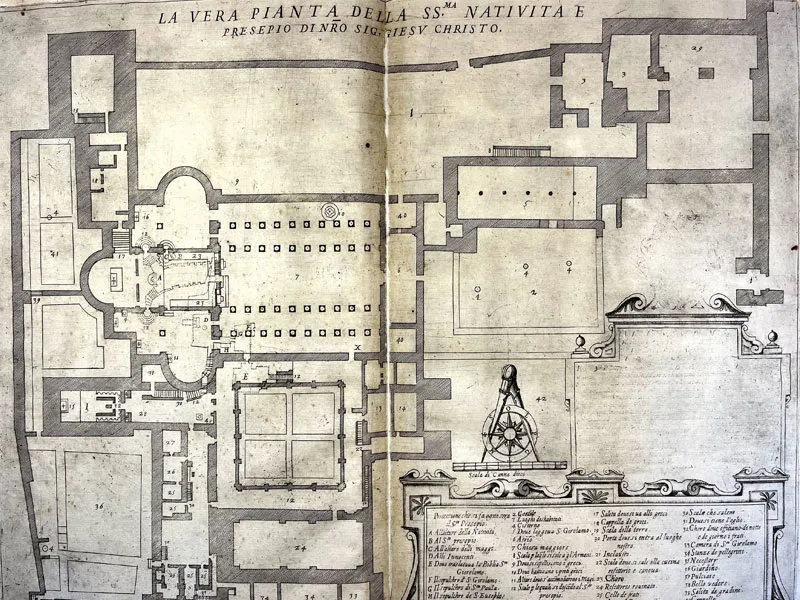

Site Architecture and Layout

At the heart of the Nativity complex lies the Grotto of the Nativity, a cave revered as the place where Jesus is believed to have been born. Surrounding the Grotto, the central elements of the complex include the Church of the Nativity and the adjacent Catholic Church of St. Catherine to the north.

Outer Courtyard

Bethlehem’s main city square, Manger Square, is an extension of the large paved courtyard in front of the Church of the Nativity and St Catherine’s. Here crowds gather on Christmas Eve to sing Christmas carols in anticipation of the midnight services

Basilica of the Nativity

The primary Basilica of the Nativity is overseen by the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Its architectural layout resembles that of a typical Roman basilica, characterized by five aisles delineated by Corinthian columns, with an apse located at the eastern terminus housing the sanctuary.

Access to the basilica is granted through a notably low entrance called the “Door of Humility.”

Within the church’s interior, remnants of medieval golden mosaics once adorned the side walls, though significant portions have since been lost.

While the original Roman-style flooring has been obscured by flagstones, a trap door in the floor provides a glimpse into the original mosaic pavement from the Constantinian basilica.

The basilica features 44 columns dividing the aisles from the nave and from each other, some of which are embellished with depictions of saints, including Catald, the Irish monk from the 7th century, Canute IV, the king of Denmark (c. 1042–1086), and Olaf II, the king of Norway (995–1030).

Towards the eastern portion of the church, a raised chancel is enclosed by an apse housing the main altar, separated from the chancel by a sizable gilded iconostasis.

Throughout the entire structure, an intricate arrangement of sanctuary lamps is positioned.

The uncovered ceiling reveals wooden rafters, recently restored. The 15th-century restoration utilized beams donated by King Edward IV of England, along with lead for the roof; however, the lead was confiscated by the Ottoman Turks, who repurposed it for ammunition in their conflict against Venice.

Adjacent staircases flanking the chancel provide access down to the Grotto.

Grotto of the Nativity

The Grotto of the Nativity, believed to be the birthplace of Jesus, is an underground chamber forming the crypt beneath the Church of the Nativity. Positioned beneath its primary altar, it is typically accessed via two staircases flanking the chancel. This grotto is part of an interconnected network of caves, reachable from the neighboring Church of St. Catherine’s. The passage linking the Grotto to the other caves is usually secured.

Within the cave, an eastern recess is identified as the spot where Jesus was born, housing the Altar of Nativity. Beneath this altar lies a 14-pointed silver star, bearing the Latin inscription Hic De Virgine Maria Jesus Christus Natus Est-1717 (“Here Jesus Christ was born to the Virgin Mary”-1717). Initially installed by Catholics in 1717, it was purportedly removed by the Greeks in 1847 and subsequently replaced by the Turkish government in 1853. The star is embedded in the marble floor and encircled by 15 silver lamps, representing the Greek Orthodox, Catholics, and Armenian Apostolic communities. Maintained by the Greek Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic churches, the Altar of the Nativity symbolizes the three sets of 14 generations in the genealogy of Jesus Christ.

Catholics oversee a portion of the grotto known as the “Grotto of the Manger,” marking the traditional site where Mary placed the newborn baby Jesus in the manger. Opposite this location is the Altar of the Magi.

Church of St. Catherine

The adjacent Church of St. Catherine is a Catholic establishment dedicated to Catherine of Alexandria, constructed in a more contemporary Gothic Revival architectural style. It has undergone further enhancements in accordance with the liturgical changes following Vatican II.

This church serves as the venue where the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem conducts Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve. While some traditions observed during this service predate Vatican II, they must be upheld due to the legally binding Status Quo established by a decree (firman) in 1852 under the Ottoman Empire, which remains in effect today.

A notable addition to the Church of St. Catherine is the bas-relief sculpture of the Tree of Jesse, measuring 3.75 by 4 meters (12 ft 4 in by 13 ft 1 in), created by Czesław Dźwigaj. Presented as a gift from Pope Benedict XVI during his visit to the Holy Land in 2009, this artwork portrays an olive tree representing the genealogy of Jesus from Abraham through Joseph, along with symbolism drawn from the Old Testament. At the top, a crowned figure of Christ the King is depicted with open arms, bestowing blessings upon the Earth. The sculpture is prominently displayed along the path frequented by pilgrims en route to the Grotto of the Nativity.

Caves Accessed from St. Catherine’s

Numerous chapels are situated within the caves accessible from St. Catherine’s, each with its own significance. Among them is the Chapel of Saint Joseph, which honors the angel’s visit to Joseph, instructing him to escape to Egypt. Additionally, there is the Chapel of the Innocents, dedicated to commemorating the children slain by Herod. Lastly, there is the Chapel of Saint Jerome, located in an underground cell traditionally believed to be where he resided while translating the Bible into Latin.

Tombs

Traditional Tombs of Saints

In accordance with a tradition lacking historical evidence, it is believed that the tombs of four Catholic saints rest beneath the Church of the Nativity, within the caves accessible from the Church of St. Catherine. These saints include Jerome, whose remains are purported to have been relocated to the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome; Paula, a disciple and supporter of Jerome; Eustochium, Paula’s daughter; and Eusebius of Cremona, a follower of Jerome. However, an alternate tradition suggests that Eusebius is interred in Italy.

Ancient Burials

Numerous ancient trough-shaped tombs are visible in the caves belonging to the Catholic Church, situated near the Nativity Grotto and St. Jerome’s Cave. Some of these tombs are located within the Chapel of the Innocents. Additionally, more tombs can be observed on the southern side of the Basilica of the Nativity, under the ownership of the Greek Orthodox Church, purportedly belonging to the infants massacred by Herod.

According to researcher Haytham Dieck, rock-cut tombs and bone fragments found in a restricted area of the church date back to the 1st century AD. In another secluded chamber known as the Cave of the Holy Innocents, skulls and other skeletal remains from possibly up to 2,000 individuals (as claimed by Dieck) are stored, although they are clearly not infant remains.

Christmas in Bethlehem

In Bethlehem, the celebration of Christmas Eve and Christmas Day occurs on three different dates:

December 24 and 25 are observed by the Catholics (Latins), adhering to the General Roman Calendar (Gregorian).

January 6 and 7 are commemorated by the Greek Orthodox, Syriac Orthodox, Ethiopian, and Coptic Orthodox, following the Julian calendar.

January 18 and 19 are reserved for the Armenian Apostolic Church. They combine the observance of the Nativity with that of the Baptism of Jesus into the Armenian Feast of Theophany on January 6, following the early traditions of Eastern Christianity. However, their calculations abide by the rules of the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem (January 6 Julian style corresponds to January 19 Gregorian style).

Latin and Protestant

The Catholic Midnight Mass in Bethlehem on Christmas Eve is globally televised. The festivities commence hours before, with dignitaries greeting the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem near Rachel’s Tomb at the city entrance. Accompanied by a procession of youth organizations, he proceeds to Manger Square, where eagerly awaiting crowds gather. Following Mass at the Catholic Church of Saint Catherine, the patriarch leads the congregation to the adjacent Church of the Nativity. Carrying a figurine of the Baby Jesus, he reverently places it on the silver star in the Nativity Grotto beneath the basilica.

Protestants have the option of worshipping either at the Lutheran church or the Church of the Nativity. Alternatively, some Protestant congregations opt to gather in Beit Sahour, a village near Bethlehem.

Greek Orthodox

Thirteen days later, on Orthodox Christmas Eve, Manger Square once again teems with visitors and faithful individuals. This time, the square hosts processions and receptions honoring the religious leaders of various Eastern Orthodox communities.

Armenian

Members of the Armenian community are the last ones to celebrate Christmas, on January 18 and 19, in their own section of the Nativity Church.The altars there are also used by the smaller denominations during their respective Christmas festivities.

Annual Feast Day

Feast Day: December 24 and 25

The annual feast day of Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem, is celebrated on December 24 and 25 for the Catholics every year at Thumpoly Church.

Church Visiting Hours

Summer (April – September) : 6:30 a.m. – 7:30 p.m.,

Winter (October – March) : 5:30 a.m. –5:00p. m.

Contact Info

P635+P2C,

Bethlehem,

Territory,

Accomodations

Connectivities

Airway

The nearest major airport to the Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem is Ben Gurion Airport,. which is 64 km away from the Shrine.

Railway

The nearest Railway to the Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem is Tel Aviv Ha’Hagana Railway Station,. which is 69 km away from the Shrine.