Introduction

The Cathedral of Sigüenza, officially known as the Catedral de Santa María de Sigüenza, stands as a historic and architectural landmark in the town of Sigüenza, located in the Castile-La Mancha region of Spain. Serving as the episcopal seat of the Diocese of Sigüenza-Guadalajara, this cathedral is dedicated to Santa María la Mayor, the Virgin Mary, who is also the patron saint of the city. The cathedral’s origins trace back to January 1124, a pivotal moment when Bishop Bernard of Agen (1080–1152) reclaimed the city from Muslim control during the reign of Queen Urraca of León, daughter of Alfonso VI of León and Castile. Bernard had been appointed bishop three years earlier in 1121 by Bernard of Sédirac, the Archbishop of Toledo and a prominent figure of the Cluniac monastic order, which significantly influenced the region’s religious and cultural development.

Following the reconquest, Alfonso VII granted Bishop Bernard privileges and donations aimed at revitalizing and increasing the population, effectively uniting the two distinct areas of the city: the upper town centered around the castle, and the lower Mozarabic settlement by the Henares River. Over the centuries, the cathedral evolved architecturally, reflecting the styles of successive periods and patrons. Its Gothic central nave, completed in the 15th century, stands out as a masterpiece of medieval design, while significant 16th-century renovations replaced the original Romanesque side apses with an ambulatory. The cathedral’s imposing facade features two outer towers adorned with merlons, giving it a fortress-like appearance—an architectural characteristic common among religious buildings of the era, designed to serve both spiritual and defensive functions. This dual role earned the cathedral the nickname “fortis seguntina,” underscoring its significance not only as a place of worship but also as a bastion of protection for the city.

Historical Context

The origins of the Cathedral of Sigüenza are closely tied to the turbulent political and religious landscape of early 12th-century Spain. Queen Urraca of León, the daughter of Alfonso VI, played a crucial role as the first monarch to grant tithes to the newly established bishopric of Sigüenza, solidifying its ecclesiastical authority and economic foundation. The Archbishop of Toledo, Bernard of Sédirac, a key figure of French origin and member of the Cluniac Order, appointed Bernard of Agen—also from France and a fellow Cluniac—as Bishop of Sigüenza in 1121. At the time, the city itself remained under Almoravid Muslim control. Bernard of Agen spent several years accompanying King Alfonso, husband of Queen Urraca, on military campaigns in the La Alcarria region, preparing for the eventual reconquest of Sigüenza. In 1123 or early 1124, Bernard of Agen was tasked with reconquering Sigüenza and restoring the former Visigothic episcopal see. Two 16th-century documents preserved in the cathedral mark January 22 as the date of reconquest, although the exact year is missing. However, a letter from Queen Urraca dated February 1, 1124, references the recent possession of the city, acknowledging its long period of desolation under Muslim rule—described as lasting over four hundred years—and granting the church and its bishop tithes from the nearby regions of Atienza and Medinaceli.

Bernard of Agen implemented the reforms of Pope Gregory VII by establishing the Roman rite and suppressing the Mozarabic rite in the diocese. Throughout his approximately 30-year episcopacy, he secured donations from King Alfonso VII and was granted lordship over the city, which was divided into two distinct settlements: the upper Segontia around the castle, held by the king, and the lower Segontia by the Henares River, under the bishop’s jurisdiction. Eventually, these two were unified into a single city governed by the cathedral chapter.

Bernard of Agen’s tenure was marked by ongoing conflict, as he faced frequent attacks from Muslim forces. While it is unclear if he initiated construction of the cathedral itself, his leadership laid the groundwork for its future development. He died in battle in 1152 and was succeeded by his nephew, Peter of Leucate.

Stages of Construction and Key Bishops

The precise origins and initial construction phases of the cathedral are somewhat debated. A document dated September 16, 1138, records King Alfonso VII granting land where an episcopal church had been established, which some scholars interpret as evidence for the site of the original cathedral. Historian Pérez Villamil argued that this donation implied the building of a new cathedral on sacred ground, likely where the current structure stands, albeit initially on a smaller scale. A 1144 document states that Bernard of Agen rebuilt a primitive cathedral featuring a “double wall and tower,” potentially on the remains of an ancient Visigothic or Mozarabic church known as Santa María Antiquíssima. This theory, supported by scholar María del Carmen Múñoz Párraga, situates the original cathedral construction at the site of today’s cathedral.

Other interpretations, such as that of Severiano Sardina, suggest Bernard of Agen may have built two small churches in the upper town and rebuilt another building that served temporarily as the cathedral, possibly where the Church of Nuestra Señora de los Huertos (now the Poor Clares’ church) stands. The Romanesque cathedral that followed featured a traditional three-nave floor plan and a chancel with five apses, arranged in a staggered fashion from the smaller side apses to a large central apse. Defensive towers flanked the facade, emphasizing the cathedral’s fortress-like character. By the end of the 12th century, the five altars within the apses were consecrated, aligning with ecclesiastical norms requiring multiple altars for individual masses.

Evolution Through the 12th and 13th Centuries

Under Bishop Arderico (1178–1184), the cathedral chapter moved into the cloister quarters, indicating growing institutional organization. The Cistercian monk Brother Martín de Finojosa (1185–1192) influenced the construction style, gradually transitioning it from Romanesque to early Gothic, or proto-Gothic. Bishop Rodrigo (1192–1221) oversaw significant building projects, including the construction of the main facade wall and the lower sections of the cathedral’s towers. The three Romanesque portals corresponding to the cathedral’s three naves, as well as the windows with archivolts and vegetal motifs on their capitals, date from this period. The rose window on the southern transept, adorned with small arches and circular designs, is also a 13th-century creation.

Gothic Additions and Later Renovations

The cathedral’s central nave, constructed in the 14th century, showcases the mature Gothic architectural style. The main facade’s rose window, dating from the 15th century, features multiple mouldings and an outer border decorated with diamond-shaped points, though weathering has caused some deterioration. In the 15th century, Cardinal Mendoza took charge of the works, completing the vaults of the transept and refurbishing those in the presbytery. The 16th century saw the most significant structural change with the construction of the ambulatory, which necessitated demolishing part of the original Romanesque choir and apses.

Damage and Restoration in the 20th Century

The Spanish Civil War inflicted severe damage on the cathedral in 1936. Restoration efforts began in the subsequent decades, notably between 1943 and 1949, led by the Segovian sculptor Florentino Trapero, who was responsible for restoring the damaged sculptures throughout the building. Among the post-war modifications was the addition of a large dome over the transept, a major transformation reflecting evolving architectural and restoration philosophies.

Architecture of Cathedral of the Assumption of Our Lady, Sigüenza, Spain

Architectural style : Gothic architecture

Burials : Martín Vázquez de Arce

Exterior of Sigüenza Cathedral

Western Facade and Atrium

The main facade, located on the western side of the cathedral, is primarily Romanesque in style, though it features significant Neoclassical and Baroque additions from later periods. The facade is structured into three distinct doorways corresponding to the cathedral’s three naves, separated by two massive buttresses that reinforce the structure. Flanking the main facade are two imposing sandstone towers, each with a square floor plan. These towers consist of four levels: the lower three levels feature small Romanesque windows on each side, while the fourth level contains double windows with semicircular arches. The towers are crowned with battlements and decorated with stone spheres.

The atrium, constructed in 1536 after the demolition of the front wall of the cathedral, is a large open courtyard measuring approximately 48 by 24 meters. It is supported by twenty-one limestone columns, each topped with intricately carved lions by Francisco de Baeza (1503–1542). On the northern side of the atrium is the Contaduría del Cabildo (Chapter’s Accounting Office), adorned with three elegant Plateresque-style windows. In 1783, wrought iron bars and two forged doors were added, featuring the coat of arms of Bishop Francisco Javier Delgado Venegas, along with the inscription “M. Sanchez en fecit an. 1783” and a crowning cross.

Main Doors of the Western Facade

The three main doors are Romanesque in design, each corresponding to a nave. The central door, known as the Puerta de los Perdones (Gate of Pardons), is the most prominent. It features a semicircular arch with archivolts supported by columns with capitals decorated in vegetal motifs. The first archivolt is adorned with geometric interlacing. The wooden swing doors date from 1625. Above the central door is a pediment containing a Baroque bas-relief medallion that depicts the Imposition of the Chasuble on Saint Ildefonsus. Just above this is a magnificent 13th-century Romanesque rose window with twelve spokes and intricate tracery that allows light into the central nave.

Flanking the central door are two smaller doors on the Gospel and Epistle sides, also Romanesque, each topped by semicircular arches and archivolts. Above these doors and the rose window are three ogival (pointed) arches, indicating the transition from Romanesque to Gothic architectural styles. The best-preserved of these side doors is the one on the Gospel side, showcasing rich vegetal ornamentation with large leaves, ovoid interlacing, and checkered bands on the archivolts, supported by intricately carved capitals.

Towers of the Main Facade

Originally standing as isolated defensive lookout points, the two towers flanking the western facade were later connected to the cathedral walls by a stone balustrade added in 1725. The right tower, known as Las Campanas (“The Bells”), rises to 40.5 meters and features an internal staircase with 140 steps. Its uppermost section was added in the 14th century under Bishop Pedro Gómez Barroso (1348–1358), who also covered the original masonry with dressed ashlar stone and decorated the fourth floor with the coats of arms of himself and King Peter I of Castile. The left tower, called Don Fadrique, is slightly taller at 41.7 meters. Completed in the 16th century, it displays the date 1533 and bears the coat of arms of Bishop Fadrique de Portugal inscribed on its facade.

Southern Facade (The Market Side)

Turning around the tower of Las Campanas leads to the southern facade, which corresponds to the end of the cathedral’s transept. The central and tallest nave of this facade is adorned with striking Gothic pointed-arch stained glass windows, separated by sturdy buttresses. The eaves rest on corbels carved into animal figures, alternating with metopes decorated with vegetal motifs. The windows of the lateral, lower naves showcase the architectural transition from Romanesque to Gothic styles, featuring a blend of eaves and cornices with blind arcades.

Market Gate (Puerta del Mercado)

Further east along the southern facade is the Market Gate, formerly known as Puerta de La Cadena. This Romanesque portal dates from the 12th century and faces the Plaza Mayor. It is sheltered by a Neoclassical enclosed portico, constructed in 1797 by architect Bernasconi under the commission of Bishop Juan Díaz de la Guerra. Above the doorway, a 13th-century transitional Romanesque rose window with a unique tracery design adds historic charm.

Rooster Tower (Torre del Gallo)

The Rooster Tower, dating from the early 14th century, originally functioned as a military watchtower used for signaling, visible from the nearby Castle of Sigüenza. Over the centuries, it has undergone several restorations. Crowning the central nave is a dome built during the Spanish post-war period, adding a distinct architectural element to the skyline.

Northern Facade

The northern facade largely mirrors the design of the southern facade but features a different rose window. This facade includes a tower located above the sacristy of Santa Librada on the north arm of the transept. The tower matches the height of the central nave but remains unfinished.

Eastern Facade (The Head of the Cathedral)

The eastern facade corresponds to the head of the cathedral and is distinguished by the presence of the ambulatory, a large semi-circular walkway that replaced the original five Romanesque apse chapels. This facade is punctuated by tall Gothic windows and crowned by the lantern tower associated with the presbytery, lending the area a sense of grandeur and vertical emphasis.

Interior of the Cathedral of Sigüenza

Architectural Structure and Dimensions

The Cathedral of Sigüenza is built in the form of a Latin cross, comprising three naves, a broad transept, and a deep apse that houses the main chapel. Surrounding the apse is an ambulatory, providing access around the altar area. The building measures 80 meters in length, with the transept stretching 31 meters across and the remaining naves 28 meters. The central nave rises to a height of 28 meters and is just over 10 meters wide, while the side naves reach 21 meters in height. Massive pillars, each formed by twenty attached columns with plant-themed capitals, separate the naves. From these capitals spring the ribs that form the pointed ribbed vaults, mostly simple in design, though sexpartite vaults appear in the transept and an octopartite vault crowns the dome. Notably, three of the four pillars framing the choir are unique, blending Romanesque and Gothic features.

Gospel Aisle and the Parish of San Pedro

The floor plan has evolved over time. Originally, there were no side chapels; this remains true for the Epistle nave, which only features an altar and a tomb. However, the Gospel nave now contains several chapels that extend to the cloister wall. The first chapel on this side is the Parish of San Pedro, built in 1455 by Bishop Fernando Luján. Its Plateresque entrance was created by Francisco de Baeza, while the ornate Gothic-Plateresque grille was designed by Juan Francés in 1533. Though significantly remodeled in 1675 by Bishop Pedro de Godoy, the Gothic style was preserved with the addition of three star-vaulted bays. The main altar features a statue of Saint Peter above a polychrome wood group depicting the Holy Trinity, sculpted by Mariano Bellver y Collazos in 1861. This imagery reflects Spanish Baroque iconography. The Gothic tomb of Bishop Fernando Luján, adorned with reliefs from the life of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, is also located here.

San Valero Gate and the Chapel of the Annunciation

The Gate of San Valero, constructed in the early 16th century by Domingo Hergueta, reflects a fusion of Gothic arches, Renaissance pilasters, and Mudejar motifs. It opens into the cloister and leads to the Chapel of San Valero, the oldest in the cathedral with a Romanesque layout and Gothic details. Nearby, the Chapel of the Annunciation, also known as the Chapel of the Immaculate Conception, was founded in 1515 by Fernando Montemayor. Its portal exemplifies the “Cisneros style,” combining Plateresque niches, Mudejar geometric patterns, and Gothic ornamentation. Inside is a polychrome Plateresque tomb of Montemayor and another of Bishop Eustaquio Nieto y Martín. The chapel also features a Gothic vault and a Renaissance-inspired grille by Juan Francés.

Chapel of San Marcos and Other Tombs

The Chapel of San Marcos has a richly decorated Gothic-Plateresque façade and was commissioned by Juan Ruiz de Pelegrina, who is buried inside. The altarpiece features six painted panels from the 16th century by Francisco del Rincón. Another notable tomb within the cathedral is that of Juan González Monjua and Antón González, likely uncle and nephew. Their tomb features one figure reclining on the sarcophagus and the other angled against the wall, both wearing similar garments and bonnets. The epitaph identifies them as teachers and revered figures—Juan served as an ambassador for King John II of Castile, while Antón founded a charitable institution known as the Arca de Misericordia.

Altars of the Gospel Nave

The Gospel nave concludes with several altars. The Altar of St. John the Baptist, constructed with a Plateresque arch by Francisco de Baeza in 1530, holds a later Baroque altarpiece from the 18th century. Opposite it, affixed to the choir wall, is the Altar of St. Michael, built in the 17th century, continuing the artistic and devotional richness of this nave.

The Transept and Central Dome

The transept spans over 36 meters in length and shares the same height as the central nave. During restoration following the Spanish Civil War in 1936, a dome was added at the crossing. It features a square vault with eight segments and pointed windows, bringing natural light into the structure. The north arm of the transept houses Plateresque altars dedicated to Santa Librada and Fadrique de Portugal, while the south side includes a Romanesque rose window, the Doncel Chapel, and the Altar of Our Lady of La Leche. Sexpartite vaulting covers the lateral arms of the transept.

Modern Sacristy and Porphyry Gate

Located in the northern transept is the Sacristy of Santa Librada, accessed via a richly adorned Plateresque portal by Francisco de Baeza. Adjacent to it is the Gate of Porphyry and Jasper, a 1507 Renaissance addition, made of red and yellow marble. It is one of the earliest Renaissance features within the cathedral and leads directly to the cloister.

Altarpiece and Mausoleum of Saint Librada

A centerpiece of the cathedral’s Renaissance heritage is the Altarpiece of Saint Librada, commissioned by Bishop Fadrique de Portugal and designed by Alonso de Covarrubias. Executed between 1518 and 1539, the altarpiece forms a monumental triumphal arch, combining architecture, sculpture, and painting. A silver urn containing the saint’s relics is placed beneath a coffered arch, guarded by a grille by Juan Francés. The lower altarpiece, comprising two tiers and three panels, displays six paintings by Juan Soreda that illustrate scenes from the saint’s life. Notably, the enthroned image of Saint Librada was inspired by Raphael’s Virgin of the Clouds and includes symbolic references to the Labors of Hercules, emphasizing moral fortitude and spiritual virtue.

Mausoleum of Fadrique de Portugal

Adjacent to the Saint Librada altarpiece is the Mausoleum of Fadrique de Portugal, a richly sculpted Plateresque monument. Also designed by Alonso de Covarrubias and executed by Francisco de Baeza, Sebastián de Almonacid, and Juan de Talavera, the mausoleum was completed in 1539. It includes three vertical bodies, a bench, and an attic. Highlights include the kneeling figure of the bishop accompanied by clerics, flanked by statues of Saints Peter and Paul, a relief of the Pietà, and a painted Calvary. The ensemble illustrates the harmony of Renaissance artistry and the bishop’s devotion, completing a visual and spiritual focal point within the cathedral.

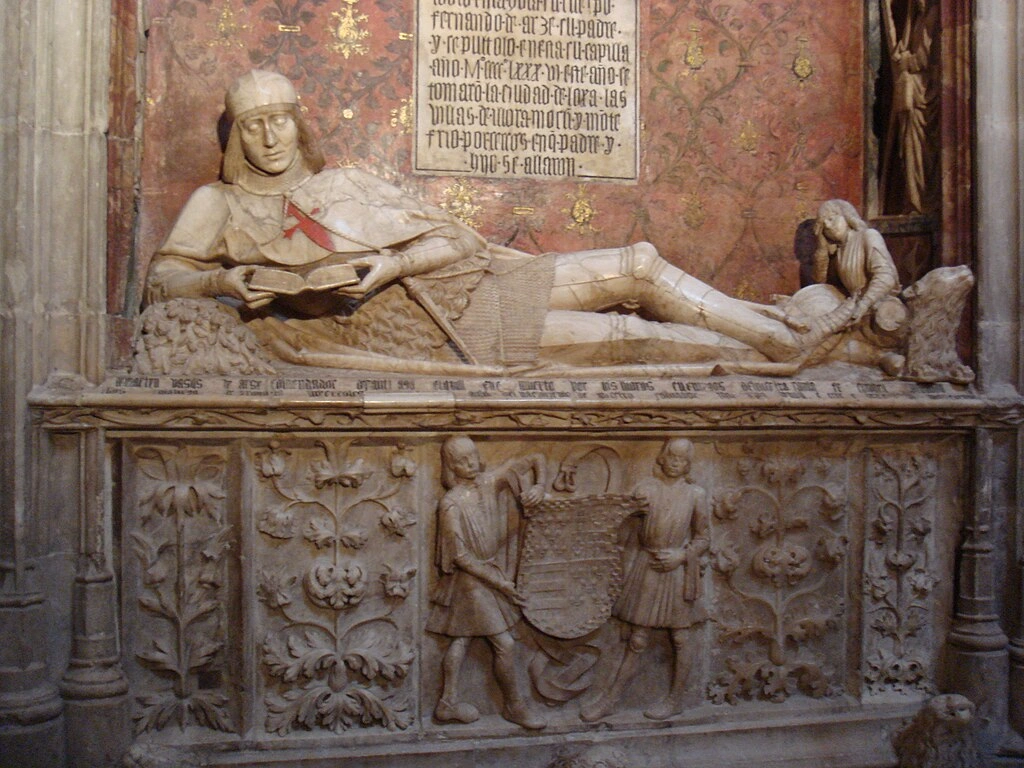

Chapel and Tomb of the Doncel

The Chapel of the Doncel, also known as the Chapel of St. John and St. Catherine, is located on the south side of the transept in Sigüenza Cathedral. Originally one of the Romanesque apse chapels dedicated to St. Thomas of Canterbury, it features a striking Plateresque-style entrance gate created by Juan Francés between 1526 and 1532, along with a finely executed doorway by Francisco de Baeza. Within the chapel lie several important Renaissance-era burial monuments, the most prominent being the tomb of Fernando de Arce and Catalina de Sosa, parents of the Doncel. Their effigies rest atop a lion-supported base, with symbolic details—such as laurels beneath Fernando’s head—indicating a warrior’s passing. Another notable tomb on the chapel wall is that of Fernando Vázquez de Arce, Bishop of the Canary Islands and brother of the Doncel, who acquired the chapel in 1487 to serve as the family’s funerary space.

At the heart of this chapel is the celebrated Tomb of Martín Vázquez de Arce, famously known as the Doncel of Sigüenza. This alabaster sculpture is widely recognized as a masterpiece of late 15th-century Spanish funerary art. In a departure from conventional recumbent effigies, the Doncel is shown partially reclined, one leg crossed over the other, and reading a book—an uncommon and symbolic pose reflecting both knightly valor and intellectual depth. He is dressed in armor, bearing the Cross of Santiago on his chest, and flanked by heraldic pages holding his coat of arms. Resting beneath a semicircular niche adorned with lions and candilieri motifs, the tomb is richly polychromed. A Latin inscription below records his death in 1486 during battle in Granada and honors his father for recovering and burying his body in this very chapel.

Altarpieces and Chapels of Sigüenza Cathedral

Adjacent to the Doncel’s tomb is the Altarpiece of Saint John and Saint Catherine, a Gothic work dating to around 1440. Originally located in the chapel’s sacristy, it displays scenes from the lives of its titular saints in an Italianate Gothic style. The central panel portrays the Crucifixion, while the predella features painted prophet figures. Notably, several panels from this altarpiece are now housed in the Prado Museum. Nearby, the Altarpiece of Our Lady of the Milk stands out for its delicate 1514 alabaster sculpture of the Virgin nursing the Christ Child, crafted by Miguel de Aleas. The surrounding architectural framework, designed by Francisco de Baeza, is in the Plateresque style, with fluted columns and decorative classical motifs, including the cathedral chapter’s coat of arms. The Ambulatory and Side Chapels, constructed in the late 16th century, replaced the original Romanesque apse chapels with a continuous corridor around the main apse. Among the chapels is that of St. John the Baptist, now a minor sacristy, and the relocated tomb of Bishop Bernard of Agén. Of special interest is the Main Sacristy, known as the Sacristy of the Heads, with its unique barrel vault adorned with more than 300 carved human heads representing a cross-section of 16th-century society. Originally designed by Alonso de Covarrubias and completed by Martín de Vandoma, it features finely carved walnut furnishings and rich Plateresque details.

The Chapel of the Holy Spirit is a square, dome-covered space accessed through an ornate wrought iron grille by Hernando de Arenas, crafted in 1561. Designed by Esteban Jamete, the chapel showcases frescoes of the Annunciation and houses saintly relics, including a notable depiction of the Eternal Father in the dome’s lantern. Another notable space within the ambulatory is the Chapel of Christ of Mercy, once a sacristy. It features a Renaissance-style entrance and contains a late Gothic vault, a Baroque altarpiece from the 17th century, and a 16th-century wooden crucifix. The intricately carved gate by Domingo Zialceta (1649) enhances its historic ambiance. Finally, the Main Chapel and High Altar, situated in the original Romanesque apse, underwent significant transformation under Cardinal Mendoza. The Mannerist-style high altarpiece was commissioned in 1608 by Bishop Mateo de Burgos and completed by sculptor Giraldo de Merlo. Rich in color and composition, the altarpiece is organized into three main levels, illustrating pivotal Christian events from the Nativity to the Ascension. Polychromy was executed by Diego de Baeza and Mateo Paredes, bringing vibrancy to one of the cathedral’s most imposing liturgical focal points.

Choir, Organ, Transept, and Side Altars

The Choir and Organ of Sigüenza Cathedral, relocated to the center of the nave by Cardinal Pedro González de Mendoza, exemplifies late Gothic artistry. The choir features 84 intricately carved walnut stalls, each uniquely adorned with Gothic tracery and episcopal coats of arms. At the center is the episcopal chair, believed to be the work of master sculptor Rodrigo Alemán, positioned beneath a finely detailed Gothic canopy. Above the choir, a gallery supports the cathedral’s organ—originally Churrigueresque in style. Following the destruction of the 18th-century instrument during the Spanish Civil War, the San Pascual organ was installed in 2011. Built by the Acitores Organ Workshop, it includes 1,390 pipes, two 56-note manual keyboards, and a 30-note pedalboard, combining traditional mechanics with modern craftsmanship.

The Transept and Altar of Saint Mary Major form a monumental Baroque ensemble. Constructed in 1666 under Bishop Andrés Bravo de Salamanca, the altar features imposing Solomonic columns made of black marble from Calatorao, alongside red and white marbles from Cehegín and Fuentes de Jiloca. At its center is a revered 12th-century Romanesque statue of the Virgin Mary, traditionally linked to Bishop Bernard of Agen and his military campaigns during the Reconquista. The image, originally adorned with silver plating in the Gothic period, was restored in 1974 to reveal its authentic polychrome wood form. Along the Right Nave (Epistle Side), although no chapels are present, several Baroque altars enhance the architectural richness. These include altars dedicated to Saint Bartholomew or Saint Cecilia, Saint Anne (dated to 1718), Saint Pascual Bailón (1691), and Our Lady of the Snows. Nearby lies the deteriorated tomb of Pedro García de la Cornudilla, dating to 1462. Despite significant damage, it remains a historical element of the cathedral’s funerary legacy.

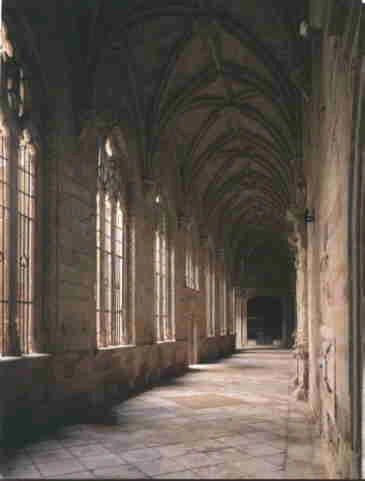

Cloister Overview

The cloister of Sigüenza Cathedral is attached to the north wall of the central building and features a quadrangular layout, each side measuring about forty meters. It includes four galleries known by different names: the northern San Sebastián’s Gallery or Cellar Gallery, the western Palace Gallery, the eastern Knights’ Gallery or Chapter Gallery, and the southern Santa Magdalena Gallery. These galleries are distinguished by their historic use for burials, with nobles, canons’ relatives, and church officials interred in different sections. The courtyard within houses a garden and a central stone fountain, surrounded by tombs along the cloister walls.

Architectural Style and Construction

Constructed beginning in 1505, the cloister replaced an older Romanesque structure that had deteriorated. Initiated by Bishop and Cardinal Bernardino López de Carvajal, with help from Cardinal Cisneros, the cloister is a late Gothic masterpiece with Renaissance influences. Its galleries are vaulted with sexpartite ribbed vaults featuring polychrome keystones decorated with coats of arms belonging to the cathedral chapter and the bishop.

Notable Cloister Features

The eastern gallery contains the Summer Chapter House, formerly the chapel of Our Lady of Peace, now a museum showcasing Flemish tapestries. The southern gallery includes the Jasper Gate, connecting the cloister to the cathedral. The northern gallery houses the Chapel of the Conception, built in 1509 by Bishop Diego Serrano for his burial. This chapel combines Gothic structure with Renaissance decoration, featuring a Gothic-Mudejar vaulted ceiling, mural paintings, and a richly decorated doorway with wrought iron grille motifs.

Chapel of the Conception

Dedicated to Bishop Diego Serrano and his family, the chapel contains his heraldic shields and an inscription commemorating his death in 1522. The chapel’s walls display murals simulating arcades with garden and city views, painted by Francisco Peregrina. Its doorway is highly ornate, framed by decorated pilasters, crowned with a stone Virgin Mary, and closed by a wrought iron grille crafted by master Usón.

Cathedral Museum

The museum spans three rooms within the cloister’s Knights’ Palace: the Chapter House (formerly the Chapter Bookstore), which features proto-Gothic vaults and Romanesque elements; the Summer Chapter House with tapestries and choir stalls; and the Old Forge Room, containing additional Flemish tapestries. The museum preserves many historic artifacts related to the cathedral’s heritage.

Tapestry Collection

Donated by Bishop Andrés Bravo de Salamanca, the cathedral’s sixteen Flemish tapestries, created by Jean Le Clerc and Daniel Eggermans in Brussels (1668), depict scenes from the story of Romulus and Remus and the mythological virtues of Athena. These valuable works are displayed seasonally in the Main Chapel.

Historical Flags

The cathedral’s flag collection includes significant military banners, notably a Portuguese and an English flag captured in the 1589 naval Battle of Lisbon by a descendant of the Doncel of Sigüenza. The collection also holds the mid-17th-century flag of the Provincial Regiment of Sigüenza, recently recovered by local preservation groups.

Feast Day

Feast Day : 15 August

The Cathedral of Saint Mary of Sigüenza celebrates its main feast day on August 15, in honor of Santa María la Mayor, aligning with the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. This day is marked by a floral offering and a special Mass, drawing locals and visitors alike.

Church Mass Timing

Monday to Saturday : 11:00 am

Sunday : 10:30 am

Church Opening Time:

Monday to Friday : 10:30 am – 2:00 pm, 4:00 pm – 7:30 pm

Saturday to Sunday : 10:30 am – 7:30 pm

Contact Info

Address : Cathedral of the Assumption of Our Lady

Pl. del Obispo Don Bernardo, 6, 19250 Sigüenza, Guadalajara, Spain.

Phone : +34 662 18 75 08

Accommodations

Connectivities

Airway

Cathedral of the Assumption of Our Lady, Sigüenza, Spain, to Adolfo Suárez Madrid–Barajas Airport (MAD), distance 1 hr 19 min (119.5 km) via A-2.

Railway

Cathedral of the Assumption of Our Lady, Sigüenza, Spain, to Sigüenza Railway Station, distance between 4 min (1.2 km) via C. Mayor and C. Bajada de San Jerónimo.