Introduction

The Valley of the Fallen, officially renamed the Valley of Cuelgamuros in 2022, is an imposing monumental complex located in the Cuelgamuros Valley of the Guadarrama Mountains, within the municipality of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, in the Community of Madrid, Spain. Situated approximately 9.5 kilometers north of the historic monastery of El Escorial and about 50 kilometers northwest of Madrid, this complex is renowned for its vast scale and striking architectural features. It encompasses a Catholic basilica, an abbey, and a monumental cross towering 150 meters high atop a cliff that overlooks the surrounding valley. Uniquely, the basilica itself is constructed entirely underground, adding to the complex’s distinctive character. Commissioned in 1940 by General Francisco Franco, the Valley of the Fallen was conceived as a memorial to those who died in the Spanish Civil War. Its construction spanned nearly two decades, from 1940 to 1958, relying heavily on the forced labor of Republican political prisoners alongside paid workers. The architectural design was led by Pedro Muguruza and Diego Méndez, while the sculptural works were primarily created by Juan de Ávalos y Taborda. The monument stands as a prominent example of Francoist architecture, characterized by its monumental scale and symbolic design. The cross, with arms stretching 24 meters each, holds the distinction of being the tallest cross in the world.

Owned by the Santa Cruz del Valle de los Caídos Foundation and managed by Spain’s National Heritage since it opened to the public on April 1, 1959, the site has attracted between 150,000 and 500,000 visitors annually since the 1990s. Initially intended as a mausoleum for Franco himself and José Antonio Primo de Rivera—the founder of the Spanish Falange—remains of soldiers from both the Nationalist and Republican sides of the Civil War were later interred there. Today, the Valley contains the remains of 33,833 combatants from both factions, making it one of the largest collective burial sites in Spain. The intermingling of remains and their integration into the structure have made any exhumation efforts highly complex. In recent years, the site has been subject to restoration efforts and increased public attention, especially around the 2019 exhumation of Franco’s remains, which were relocated to the Mingorrubio cemetery in accordance with his wishes. In 2023, José Antonio Primo de Rivera’s remains were also exhumed and transferred to San Isidro cemetery, fulfilling his family’s request. The Valley of the Fallen remains a potent and controversial symbol of Spain’s 20th-century history.

Location

The Valley of the Fallen is located in the Cuelgamuros Valley at the southern end of the Guadarrama Mountains, within the municipality of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Madrid, Spain. The area features rugged granite formations and is covered mainly by coniferous forests, with oaks, elms, and shrubs like rosemary and thyme. The site spans about 1,365 hectares, bordered by nearby municipalities and estates, with elevations ranging from 985 to 1,758 meters above sea level. The monument’s large cross stands at around 1,400 meters on the Risco de la Nava, designed to be visible from Madrid on clear days. Originally called Pinar de Cuelga Moros, the land was expropriated from its last private owner, the Marquis of Muñiz. Cuelgamuros lies nearly equidistant from Madrid, Ávila, and Segovia, and is accessible via the M-527 highway.

Origins and Symbolism

The Valley of the Fallen (Valle de los Caídos) stands as one of the most monumental legacies of Francisco Franco’s regime in Spain. Conceived as a grandiose memorial, its purpose was to honor those who died fighting on the Nationalist side during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). The monument embodies the Francoist ideology, symbolizing the victory of Franco’s forces and commemorating the “fallen for God and Spain.”

Following the end of the Civil War, Spain was dotted with numerous crosses, plaques, and monuments dedicated to Nationalist soldiers. Among these, the Valley of the Fallen emerged as the regime’s most ambitious project—a colossal, state-sponsored site designed to glorify the Francoist cause and commemorate the regime’s martyrs. Franco himself regarded the monument as a personal mission, intending it to serve as a lasting symbol of the “New Spain” born from the war’s sacrifices. The project was not merely commemorative but was imbued with deep political and ideological significance, linking Franco’s regime to Spain’s historical legacy of Catholic Monarchs and imperial grandeur.

Franco’s Cult of the Fallen

Central to Francoism was the veneration of those who died in the Civil War fighting for the Nationalist cause. This cult of the fallen was more than mere remembrance; it was a core element of the regime’s identity and propaganda. Historian Zira Box describes this as a “symbolic construction” in which the war and especially the sacrifice of the fallen were essential to the regime’s legitimacy. Franco and his supporters portrayed the bloodshed of the war as a necessary sacrifice that paved the way for Spain’s redemption and rebirth under his leadership. Franco himself declared, “There is no redemption without blood,” emphasizing the sacred nature of the conflict and those who died for it. This ideology was deeply tied to the rhetoric of the Spanish Falange, the regime’s official party. The Falangists, inspired by Italian Fascism, ritualized the memory of their “young fallen” comrades, incorporating ceremonies and commemorations that merged political martyrdom with religious sacrifice. Over time, these rituals became official state ceremonies, embedding the cult of the fallen deeply into Spanish public life.

Political Context and Repression

The Valley of the Fallen and other commemorative acts must be understood in the context of Franco’s refusal to reconcile with the defeated Republicans. The regime viewed the vanquished not as fellow citizens but as irredeemable enemies. As Franco’s close associate Ramón Serrano Suñer put it, the defeated were a “criminal enemy” who must be excluded from the nation’s future. After the war, Spain was deeply divided, and the regime enforced a harsh policy of repression, punishment, and social exclusion against Republican sympathizers. Franco openly rejected amnesty or reconciliation, instead promoting a narrative of repentance and punishment as necessary for the “redemption” of defeated Spaniards. The monuments to the fallen were thus political tools that reinforced the regime’s victory, celebrated its ideals, and suppressed the memory and presence of the defeated.

Construction and Design of the Valley of the Fallen

The conception and execution of the Valley of the Fallen was marked by a fusion of political ambition, architectural grandeur, and ideological symbolism, reflecting Francisco Franco’s vision for a monument that would immortalize the Nationalist cause and the values of his regime. The official decree for its construction was issued on April 1, 1940 exactly one year after the Nationalists’ victory in the Spanish Civil War establishing the monument’s stated purpose as honoring the “heroes and martyrs” who had died for “God and Fatherland.” Franco handpicked the site at Cuelgamuros Valley, nestled in the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains near El Escorial. The location was strategically chosen for its natural solemnity, spiritual seclusion, and symbolic proximity to Spain’s royal pantheon. The remoteness and majesty of the landscape were intended to elevate the structure beyond mere politics, presenting it as a sacred space of national and religious transcendence.

Architecturally, the project was entrusted first to Pedro Muguruza, a prominent regime architect, and later to Diego Méndez after Muguruza fell ill. Franco did not remain a distant overseer but took an active role in shaping the monument, visiting the site frequently, requesting design changes, and insisting on features that matched his ideological goals. Among these was the decision to double the size of the basilica’s crypt and to erect the colossal 150-meter cross—still one of the tallest in the world—towering above the monument as a physical and spiritual beacon of Francoist Spain. Méndez described the site as the “Altar of Spain,” envisioning it not just as a burial place but as a sacred center of national renewal rooted in heroic sacrifice, Catholic tradition, and militaristic strength. Franco wanted the monument to reflect the supposed “racial virtues” and stoic character of the Spanish people as interpreted by the regime. Artistic elements of the complex were carefully designed to reinforce these values. Sculptor Juan de Ávalos created massive statuary for the site, including the four Evangelists and the four cardinal virtues each portrayed as solemn, muscular male figures in line with Franco’s insistence on strength and masculinity. The monumental Pietà that crowns the entrance to the basilica was revised under Franco’s supervision to ensure it embodied sorrow, power, and spiritual endurance, rather than softness or fragility.

Religious function was equally essential to the monument’s purpose. To manage this, Franco established a Benedictine monastery adjacent to the basilica, charging the monks with the responsibility of maintaining liturgical and commemorative functions. The religious life at the monument was carefully orchestrated to align with Francoist ideology, with special masses commemorating regime milestones and fallen Nationalists. The first abbot, Fray Justo Pérez de Urbel a Benedictine monk, historian, and staunch Franco supporter was personally appointed by Franco to ensure full ideological alignment between Church and State. The liturgical calendar incorporated dates like the “Feast of the Triumph of the Holy Cross,” which held both religious and political resonance under the regime. Politically and socially, the Valley of the Fallen became a centerpiece of the Francoist narrative. It functioned not only as a sacred memorial but also as a space for annual state rituals, political gatherings, and nationalist pilgrimages. The site’s exclusionary design honoring only Nationalist victims while ignoring or marginalizing Republican dead made it a symbol of the regime’s one-sided version of history. It embodied Franco’s refusal to reconcile with the defeated, perpetuating a narrative of holy war and redemption through sacrifice that defined Spanish public memory for decades. Rather than healing the wounds of civil conflict, the monument enshrined the victory and ideology of the victors in stone and ritual, institutionalizing division and triumphalism at the heart of Spain’s most sacred political space.

Construction of the Monument to the Fallen

The construction of the Valley of the Fallen was a monumental effort marked by ambition, delay, and controversy. Initially intended to be completed in just five years, it ultimately took nearly two decades. Franco envisioned the crypt finished by 1941 to coincide with the anniversary of his Civil War victory, but technical and logistical challenges delayed the work. To expedite progress, the regime established the Council of Works in 1941, granting it authority to bypass bureaucratic barriers and ensure adequate funding. While early financing came from public donations, the state soon covered the majority of costs, underlining the project’s political importance. Several prominent Spanish construction companies such as San Román (later Agromán), Molán, and Banús played key roles, and their involvement helped establish their long-term prominence. A particularly controversial aspect was the use of political prisoners as laborers under the “redemption through work” system. These prisoners, mostly Republican detainees, worked in difficult and often hazardous conditions, living in makeshift shelters alongside free laborers. Despite harsh winters and physically demanding tasks like tunneling and stone cutting, some prisoners chose to remain after serving their time, unable to find work elsewhere.

At its peak, around 2,000 people were employed at the site, and over the years, roughly 20,000 workers participated in the project. Safety conditions were poor, with limited protective equipment. Official records cite 14 to 18 deaths, though unreported injuries and cases of silicosis a lung disease from granite dust exposure were common. Some attempted to escape, but few succeeded. Ultimately, the monument became not just a symbol of Francoist triumph, but also a site of suffering and repression, built by the very people it sought to silence.

Financing the Valley of the Fallen

The financing of the Valley of the Fallen remains a contentious aspect of its legacy, characterized by conflicting narratives and significant public expenditure. According to architect Diego Méndez’s records—considered the most reliable source by journalist Daniel Sueiro—the total cost of the project reached approximately 1.086 billion pesetas, with major expenses concentrated in the crypt, cross, exedra, and monastery. Although initially intended to be funded through a national subscription following the 1940 founding decree, a 1941 amendment allowed for substantial state financing. In practice, only about 235 million pesetas were raised through public contributions—roughly one-quarter of the total—while the remainder came from government funds. Despite this, official rhetoric insisted the monument was financed entirely by voluntary donations and wartime savings, a narrative reinforced through public statements and visitor materials. Critics at home and abroad questioned the scale of spending in a country grappling with economic hardship. American observers in 1954 expressed concern over the extravagant use of public funds, arguing that the money would have been better spent on housing or infrastructure. Franco responded by defending the project as a noble tribute to the fallen, likening it to Philip II’s construction of El Escorial. Today, although the Valley generates modest revenue through tourism—about two million euros annually—it continues to operate at a loss, with a reported deficit of 2.5 million euros between 2014 and 2017, underscoring the ongoing financial and political complexities surrounding the site.

Opening of the Valley of the Fallen

The Valley of the Fallen was officially inaugurated on April 1, 1959, two decades after the Spanish Civil War ended, under a highly symbolic and politically charged atmosphere. Prior to the opening, Franco had established the Foundation of the Holy Cross of the Valley of the Fallen through a 1957 decree, presenting the site as a monument to all who died “for God and for Spain.” While the rhetoric promoted unity and reconciliation, the reality was far more complex. The official language emphasized national healing, but burial policies remained exclusive—restricted to Spanish Catholics, effectively excluding many Republican victims. Though Republican remains were later transferred to the site, often without family consent or knowledge, the decision was more about filling the vast crypt and gaining international legitimacy than genuine reconciliation. Franco’s own statements and the inscriptions at the site made clear that the monument primarily honored Nationalist martyrs. The inauguration ceremony itself reflected this triumphalist tone, with Franco glorifying “our fallen” and dismissing the defeated as enemies of Spain. Media coverage echoed this narrative, portraying the event as a reaffirmation of the 1939 Victory. The site soon became a locus for Francoist commemorations, particularly on November 20, the anniversary of José Antonio Primo de Rivera’s death, and later Franco’s own. Franco was buried at the Valley in 1975, opposite Primo de Rivera, solidifying its association with the dictatorship. In the decades since, the monument has sparked ongoing controversy due to its Francoist symbolism and use of forced labor during construction. Efforts to redefine its meaning culminated in the 2007 Law of Historical Memory and the 2022 Law of Democratic Memory, which renamed the site the Valley of Cuelgamuros and prohibited political glorification of the dictatorship. Today, it is being repurposed as a space for education, democratic remembrance, and honoring all Civil War victims, though debates about its legacy persist in Spanish society.

Architecture of Basilica of the Holy Cross, El Valle de los Caídos, Madrid, Spain

Architect : Pedro Muguruza, Diego Méndez

Overview of the Complex

The Valley of the Fallen complex encompasses several major structures, including the Abbey of the Holy Cross of the Valley of the Fallen, a functioning Benedictine abbey currently led by Abbot Santiago Cantera. Also within the complex is a hostel that serves visiting tourists, a vast subterranean basilica, and the site’s most iconic feature: an enormous monumental cross that towers over the landscape. Designed as both a spiritual and political monument, the complex integrates architecture, religious symbolism, and authoritarian ideology in a striking natural setting.

Basilica Interior and Artistic Design

The basilica’s interior reflects a fusion of artistic rigor and austere monumentality, shaped by the collaborative efforts of several prominent Spanish artists, many of whom held varying political beliefs. Working under the architectural direction of Pedro Muguruza and later Diego Méndez, the artists contributed to an interior that is intentionally solemn. The flooring is composed of highly polished marble and granite, designed to reflect light and create a sense of sacred clarity. The walls are lined with ashlar-cut granite, while the vaulted nave is structured by three grand transverse arches. These arches support a ceiling formed of coffered panels, simulating the natural rock texture of the surrounding cliff, reinforcing the sense that the basilica emerges organically from the mountain itself.

Entrance, Juanelos, and the Monumental Cross at the Valley of the Fallen

Visitors entering the Valley of the Fallen are first met by a solemn and imposing gate divided into three sections, with two massive stone pillars framing a metal fence topped by the Cross of the Valley and a double-headed eagle, symbols closely associated with the Francoist regime. Below this, the coat of arms of Spain is flanked by Franco’s personal emblem on the left and the Benedictine Order’s emblem on the right. Smaller gates on either side accommodate tourist vehicles, leading to a gently ascending road winding through reforested landscapes populated mainly by pines, along with cypresses, firs, spruces, and other native trees, creating a peaceful natural setting. Along this route stand the “Juanelos,” four towering granite monoliths originally quarried in the 16th century for an ambitious but unfinished water-lifting device devised by engineer Juanelo Turriano. These columns, now acting as a monumental gateway, echo a local folk song that humorously remarks on their prolonged journey to Toledo. Dominating the complex is the monumental cross, the tallest Christian cross in the world at 150 meters tall, perched atop the Nava cliff which adds another 150 meters of elevation. The cross is composed of a 25-meter base adorned with sculpted figures of the four Evangelists and their symbols, a 17-meter section representing the cardinal virtues, and a 108-meter shaft, with arms spanning 46.4 meters wide—wide enough for two vehicles to pass side by side inside. Constructed from reinforced concrete and steel and clad in quarried stone, the cross was built without scaffolding, raised internally like a chimney, with staircases and a freight elevator built simultaneously inside. Visitors once reached the cross via a funicular railway climbing steeply up the mountain, though it has been closed since 2009; alternative access includes a hiking path and a restricted elevator inside the mountain, allowing visitors to experience the monument’s impressive scale and solemn presence firsthand.

Basilica Overview and Architectural Design

The Valley of the Fallen’s basilica is an impressive underground structure carved into the Risco de la Nava cliff. Its initial architectural plans were drafted by Pedro Muguruza, but the project was later completed and modified by Diego Méndez, who opened the originally enclosed semicircular arches to create a grand porticoed gallery by partially removing the cliff. Visitors access the basilica via a large esplanade made from the excavated mountain material. The semicircular portico features arches with cushioned voussoirs framed by simple lines, forming a monumental entrance. The massive bronze doors, measuring 10.4 meters high and 5.8 meters wide, were crafted by Fernando Cruz Solís following a 1956 competition and depict the fifteen mysteries of the rosary alongside an apostolate.

Sculptural Decoration: La Piedad and Guardian Angels

Above the portal sits the monumental sculptural group La Piedad, created by Juan de Ávalos from Calatorao stone, stretching 12 meters wide and 5 meters high, symbolizing sorrow and compassion. Inside, the crypt extends 262 meters, reaching a height of 41 meters at the transept. The vestibule, atrium, and intermediate spaces each span 11 meters in width and height, sharing an aesthetic harmony characterized by vaulted ceilings and pilasters. Two colossal bronze archangels by Carlos Ferreira stand vigil in large niches within the intermediate space, symbolizing peace by resting their swords and raising their wings. These were reportedly cast from war cannons, embodying the monument’s message of reconciliation.

Entrance Halls, Nave, Chapels, and Memorial Sculptures of the Basilica

Visitors entering the basilica descend from the intermediate space by a symbolic flight of ten steps to reach an ornate wrought-iron gate designed by José Espinós. This gate, inspired by the intricate Plateresque style typical of Spanish religious architecture, is divided into three sections supported by four sturdy piers. These piers are adorned with forty saintly figures, with Saint James the Apostle Spain’s patron saint prominently positioned at the center beneath a cross flanked by angels, while additional insignias representing angels and martyrs crown the structure. Beyond the gate lies the basilica’s great nave, set at a lower level to highlight the presbytery and create visual interest within the otherwise vast crypt. The nave is segmented into four parts by massive transverse arches that form coffered ceilings overhead. Originally, the underground space measured 11 by 11 meters, but due to the granite cliff’s challenging geology, extensive excavation and reinforcement were necessary. The resulting structure is fortified with large concrete arches and solid flooring to support the immense stone vault above. Flanking the nave are six chapels dedicated to various Marian invocations, reflecting the Virgin Mary’s patronage over land, sea, and air forces, which hold significant historical importance in Spain. The right side chapels honor the Immaculate Conception, Our Lady of Mount Carmel, and Our Lady of Loreto, while those on the left pay tribute to Our Lady of Africa, Our Lady of Mercy, and Our Lady of Pilar. These chapels are decorated with simple yet elegant altar frontals and 15th-century Flemish Gothic-style triptychs hand-painted on leather by the Lapayese family, depicting scenes from the lives of Christ and the Virgin Mary. Additionally, alabaster statues of the apostles, crafted by Lapayese, stand along the chapel walls, replacing Judas Iscariot with Saint Matthias. Interspersed between the chapels hang eight exquisite tapestries illustrating the Apocalypse of Saint John, which are faithful copies of a 16th-century Flemish series once housed in the Palace of La Granja. To reach the transept, visitors ascend a staircase of ten steps where they are met with solemn sculptures by Antonio Martín and Luis Sanguino. These statues, placed on pilasters lining the ascent, represent fallen soldiers from land, sea, and air forces as well as volunteers. Their bowed heads and covered faces invite a contemplative silence, while the rough texture of their garments contrasts poignantly with the polished realism of their faces and arms, highlighting both their sacrifice and humanity. The transept itself contains rows of pews for worshippers, seamlessly combining the basilica’s roles as both a sacred space and a solemn war memorial.

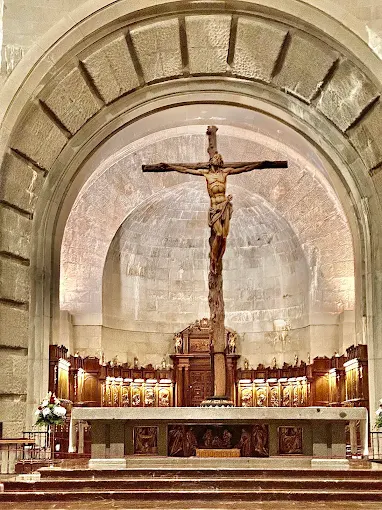

The Transept and Central Altar

At the heart of the transept, the basilica’s decorative style shifts from the nave’s designs, yet achieves harmony through deliberate contrast. The murals adopt a rigidly classical layout, which is visually punctuated by the four triumphal arches supporting the dome’s cap, constructed from splayed, cushioned voussoirs. Centrally located beneath the monumental exterior cross stands the high altar, crafted from a single, polished granite slab. The altar’s front is adorned with a gilt sheet metal bas-relief of the Holy Burial, designed by architect Diego Méndez and executed by José Espinós, while the back features a relief depicting the Last Supper. Flanking the altar are the “Tetramorphs,” symbolic representations of the four evangelists: the bull of Saint Luke, the lion of Saint Mark, the angel of Saint Matthew, and the eagle of Saint John. Above the altar, a crucifix carved by Julio Beobide and polychromed by Ignacio Zuloaga provides the sole decoration, drawing the eye upward in solemn reverence. The transept’s lateral arms, each 12.80 meters wide, conclude in two chapels the Chapel of the Most Holy and the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre.

Presbytery Surroundings: The Archangels

Surrounding the presbytery are four monumental bronze archangel statues, each standing seven meters tall and created by sculptor Juan de Ávalos. These figures Saint Raphael, Saint Michael, Saint Gabriel, and Saint Uriel (also known as Yezrael or Azrael) are richly symbolic. Saint Raphael is depicted with his pilgrim’s staff and the fish from the biblical healing of blindness. Saint Michael holds a sword, symbolizing his victory over Lucifer’s rebellion. Saint Gabriel carries a lily, referencing his role in announcing the births of the Virgin Mary and Saint John the Baptist. Saint Uriel, portrayed with bowed head and raised hands in prayer, is unique as the archangel who, according to apocryphal traditions, presents the souls of the dead before God, making him a particularly striking figure for visitors. The transept also includes three architectural fronts: the choir at the basilica’s end, the Chapel of the Sepulchre to the right, and the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament to the left.

The Dome and Its Mosaic

Rising above the transept is a magnificent dome topped with a skylight and adorned with a mosaic created by Santiago Padrós. Central to the mosaic is a Byzantine and Romanesque-inspired image of Christ Pantocrator Christ Almighty, King, and Judge depicted in majesty holding the Book of Life inscribed with “Ego sum lux mundi” (“I am the light of the world”). This figure is framed by the “mandorla,” or mystical almond-shaped aureole, formed by seraphim and cherub wings, with additional angels bearing incense and swords, reflecting biblical symbolism. Below Christ, the mosaic depicts the triumph of the Holy Cross on Mount Calvary, flanked by the crosses of the two thieves crucified alongside Jesus. To Christ’s right is a gathering of Spanish saints led by Saint James the Greater, and to the left, Spanish martyrs led by Saint Paul, encapsulating Spain’s Catholic history. Opposite this, the Assumption of the Virgin is portrayed, with angels lifting Mary heavenward from a stylized representation of Montserrat Mountain, reflecting the Virgin of Montserrat’s significance as Catalonia’s patron saint and honoring the artist’s heritage. Surrounding these scenes are depictions of fallen civilians, religious, and military figures from the Spanish Civil War, alongside symbolic flags including Spanish and Falangist banners, marking the only overt Francoist symbolism within the church. The mosaic, composed of over five million tiles, was assembled flat in Madrid’s Teatro Real and later installed on the curved dome via an indirect method. To protect the mosaic from moisture, architect Diego Méndez engineered a double-dome system with waterproof layers and ventilation space. Padrós also incorporated portraits of notable historical figures and personal acquaintances, including the philosopher Miguel de Unamuno, himself portrayed as Saint Raymond of Fitero.

The Choir

At the basilica’s head is the semicircular Renaissance-inspired choir stalls, seating seventy individuals arranged on three levels. The walnut stalls, carved by Ramón Lapayese, feature scenes of medieval warfare evocative of Crusades, with depictions of Holy Land-like dwellings. Alabaster reliefs of Benedictine saints accompany the stalls, portraying some in everyday habit and others in choir robes. Two alabaster medallions depict Saint Benedict of Nursia holding his Rule and Saint Francis of Assisi clutching a crucifix. The choir serves the monks and choirboys during Mass, connected at the rear to a gallery leading to the staircase and elevator ascending the monumental cross.

Chapels of the Sepulchre and the Blessed Sacrament

To the right of the transept lies the Chapel of the Sepulchre, housing three sculptures by Lapayese: a recumbent Christ and statues of the Virgin Mary and Saint John the Evangelist. Its ceiling boasts another mosaic by Santiago Padrós, illustrating the Holy Burial. On the left side, the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament features a silver tabernacle crafted by Espinós, adorned with reliefs of the apostles and other motifs. A 15th-century Flemish Gothic-style altarpiece crafted in the 20th century depicts the Holy Trinity in a poignant scene of sorrow, with God the Father holding the dead Christ and the Holy Spirit as a dove. This altarpiece is flanked by six apostles, and beneath it rest additional paintings of saints. The chapel’s ceiling displays a mosaic of the Ascension of Jesus Christ by Victoriano Pardo. Together, these two chapels represent the core Christian mysteries of Passion, Death, and Glory, underscoring the basilica’s role as a sanctuary of hope and eternal life amid the memory of war.

The Abbey of the Holy Cross of the Valley of the Fallen

Located on an esplanade behind Risco de la Nava, the abbey complex includes a cloister, monastery, novitiate, choir school, internal and external guesthouses, and a rear portico. Unlike typical monasteries with quadrangular cloisters, this abbey features a rectangular cloister that opens toward the monumental cross. All buildings, constructed from granite stone with hipped slate roofs, sit within a 300 by 150-meter rectangle, bordered by galleries of semicircular arches. Adjacent to the abbey is the Benedictine monks’ cemetery, accessible only by permit. A private monumental bronze door by Damián Villar González connects the basilica and the abbey. On May 27, 1958, Pope Pius XII issued the papal brief Stat Crux, formally elevating the monastery to abbey status a rare 20th-century occurrence for the Order of Saint Benedict. On July 17, 1958, the Feast of the Triumph of the Holy Cross, twenty monks from the Silos Abbey founded the new Benedictine community in the Valley.

Feast Day

Feast Day : 14 September

The Basilica of the Holy Cross at El Valle de los Caídos in Spain is dedicated to the Holy Cross, and its primary feast day is September 14, known as the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. This day commemorates the discovery of the True Cross by Saint Helena and celebrates its significance in Christian tradition. The feast reflects the basilica’s central symbol the Holy Cross and is marked by religious ceremonies and observances honoring its spiritual importance.

Church Mass Timing

Mondat to Saturday : 11:00 AM

Sunday : 1:00 PM, 5:00 PM

Church Opening Time:

Monday : Closed

Tuesday to Sunday : 10:00 AM – 6:00 PM

Contact Info

Address : Basilica of the Holy Cross

Carretera de Guadarrama, s/n, 28209 San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Madrid, Spain.

Phone : +34 918 90 54 11

Accommodations

Connectivities

Airway

Basilica of the Holy Cross, El Valle de los Caídos, Madrid, Spain, to Aeródromo Villanueva del Pardillo Camino Toconales, distance 52 min (46.8 km) via A-6.

Railway

Basilica of the Holy Cross, El Valle de los Caídos, Madrid, Spain, to El Escorial Station, distance between 27 min (18.8 km) via M-600.