Introduction

The Parish Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo (Italian: Basilica Parrocchiale Santa Maria del Popolo) is a distinguished titular church and a minor basilica located in Rome, Italy. It is administered by the Augustinian Order and stands prominently on the north side of Piazza del Popolo, one of the most famous and bustling squares in the city.

Situated between the Pincian Hill and the Porta del Popolo, one of the gates in the Aurelian Walls, the basilica occupies a strategic location that has historically made it the first church encountered by travelers entering Rome from the north. The Porta del Popolo marks the starting point of Via Flaminia, a key route that connected Rome to the northern parts of Italy and beyond, reinforcing the basilica’s role as the first stop for pilgrims and visitors entering the city. Santa Maria del Popolo holds deep historical significance due to its location and the various artistic masterpieces contained within its walls. Over the centuries, it has become a repository of works by some of the most renowned artists in the history of Western art. These include notable figures such as Raphael, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Caravaggio, Alessandro Algardi, Pinturicchio, Andrea Bregno, Guillaume de Marcillat, and Donato Bramante.

Among the church’s treasures are Caravaggio’s famous paintings, such as The Crucifixion of Saint Peter and The Conversion of Saint Paul, both of which are housed in the Cerasi Chapel. The church also contains works by Raphael, including his early frescoes, and sculptural masterpieces by Bernini and Algardi. In addition to its rich artistic heritage, Santa Maria del Popolo also plays a significant role in the ecclesiastical and social life of Rome. It is a center of worship and a symbol of the connection between art, history, and faith. The basilica’s importance is underscored by its elevation as a minor basilica and its continued association with the Augustinian Order, which has overseen its care and preservation for centuries. The church remains one of the key religious and artistic landmarks of Rome, drawing visitors for both its spiritual significance and its cultural wealth.

Legendary Founding

The founding legend of Santa Maria del Popolo is deeply entwined with the reputation of Emperor Nero and the purification of the area by Pope Paschal II. According to the legend, after Nero’s suicide, his body was buried in the mausoleum of his family, the Domitii Ahenobarbi, at the foot of Pincian Hill. The mausoleum eventually collapsed under a landslide, and a massive walnut tree grew on the site, becoming so tall and sublime that no other plant surpassed it. This tree soon became a haunt for vicious demons, who tormented the local population and travelers entering the city through Porta Flaminia, causing great suffering and fear.

Alarmed by these demonic disturbances, Pope Paschal II, upon seeing the Christians under his care becoming prey to these “infernal wolves,” decided to take action. After fasting and praying for three days, he had a vision of the Blessed Virgin Mary, who provided him with detailed instructions on how to rid the area of the evil spirits. On Thursday after the Third Sunday of Lent in 1099, the Pope organized a grand procession with clergy and laypeople, leading them along the Via Flaminia to the site of the infested tree. Paschal II performed an exorcism and struck the walnut tree’s root with a powerful blow, causing the evil spirits to burst forth in a frenzy. Once the tree was removed, the remains of Nero were discovered among the ruins and were ordered to be thrown into the Tiber River.

Following this purification, the site was deemed suitable for Christian worship. In the presence of a large crowd, the Pope laid the first stone of an altar at the very spot where the tree had stood. This marked the beginning of the church’s construction, which was completed within three days. The church was consecrated with great solemnity, and Paschal II bestowed numerous relics upon the new chapel, dedicating it to the Virgin Mary.

Historical Origins

The legendary founding story of Santa Maria del Popolo was first recounted by Giacomo Alberici, an Augustinian friar, in his treatise on the church published in 1599, and later restated by another Augustinian, Ambrogio Landucci, in 1646. Over the centuries, this tale has been retold with minor variations in collections of Roman curiosities and scientific literature. One version, for example, suggested that the demons that plagued the tree appeared as black crows.

While the historical accuracy of the legend is uncertain, some elements can be traced to real events. Nero’s mausoleum was indeed located at the top of Pincian Hill, but not at the site of the present-day church. The mausoleum was mentioned by Suetonius, who described it as being located on the “summit of the Hill of Gardens,” which is some distance from the church’s current location at the foot of the hill. The connection between the site and demons may have been part of a broader medieval effort to restore safety and reduce the criminal activity around Porta Flaminia, which was situated outside the city’s core and known for being a dangerous area plagued by bandits.

The symbolic action of throwing the remains of Nero into the Tiber River may also have been a gesture to cleanse the area, especially since Pope Paschal II had previously exhumed and thrown the remains of his rival, Antipope Clement III, into the river. Clement had been supported by the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV, who was sometimes referred to as “Nero” by the papal faction.

Etymology

The name Santa Maria del Popolo likely comes from the term populus, which in medieval Latin refers to a large rural parish or settlement. The name could thus refer to the first suburban settlement around Via Flaminia, which emerged after the chapel’s construction. Alternatively, the name could signify that the people of Rome were “saved” from the demonic scourge that had haunted the area, or it could be linked to the Latin word pōpulus meaning “poplar,” referencing the trees that might have been present around the ancient tombs. In the 15th century, some historical documents referred to the church as S. Maria ad Flaminiam.

The early history of Santa Maria del Popolo is shrouded in mystery, primarily due to the loss of many documents during the Napoleonic era. However, references to the church begin to appear in documents from the 13th century. For example, the Catalogue of Paris, which was compiled around 1230 or 1272-1276, already includes the name Santa Maria de Populo.

In medieval times, it is believed that there may have been a small Franciscan community living near the church until around 1250, though they may have only resided there temporarily. The church was originally small but grew in significance, particularly with the arrival of the miraculous image of the Virgin Mary, which was said to have been painted by Saint Luke. The story goes that Pope Gregory IX, after a devastating flood of the Tiber River in 1230, organized a solemn procession in which the Madonna del Popolo was moved to the church, helping to end a plague that had ravaged the city. This event solidified the church’s reputation as a place of divine intervention, attracting pilgrims and ensuring the church’s central role in Roman devotion.

The Augustinians at Santa Maria del Popolo

In the middle of the 13th century, the Order of Saint Augustine took over the care of Santa Maria del Popolo, and they have maintained the church ever since. The Augustinian order was relatively new at the time, founded under the guidance of Cardinal Riccardo Annibaldi, a highly influential member of the Roman Curia. Pope Innocent IV appointed Annibaldi as the corrector and provisor of the Tuscan hermits in December 1243, and Annibaldi convened a meeting at Santa Maria del Popolo for representatives of various hermitic communities. The result of this meeting was the formation of the Augustinian Order, confirmed by the Pope’s bull Pia desideria on March 31, 1244.

By 1250 or 1251, a community of Augustinian friars was established at the church, taking over from the Franciscans. In the Grand Union of 1256, initiated by Pope Alexander IV, the various hermitic communities were united under the Augustinian order, and the church of Santa Maria del Popolo played a key role in this integration. The Annibaldi family maintained a strong connection to the church, as evidenced by a 1263 inscription honoring two of its members, Caritia and Gulitia, who funded a marble monument in the basilica.

During the 15th century, the friary of Santa Maria del Popolo became part of the observant reform movement in an effort to restore the purity of monastic life. In 1449, the general chapter of the Augustinian observants established five separate congregations for observant friars in Italy, one of which was sometimes referred to as the Rome-Perugia Congregation, named after Santa Maria del Popolo. In 1472, Pope Sixtus IV gave the friary to the Lombard Congregation, the largest and most influential Augustinian branch, making it their Roman headquarters.

The Sistine Reconstruction (1472–1477)

Soon after the church’s transfer to the Lombard Congregation, Pope Sixtus IV ordered a complete reconstruction of Santa Maria del Popolo as part of his broader effort to renovate the city of Rome, earning him the title Urbis Restaurator. The medieval church was demolished, and a new, more grandiose Renaissance basilica was built. The design was in the shape of a Latin cross with four chapels on each side, an octagonal dome above the crossing, and a tall Lombard-style bell tower. This reconstruction was an early example of Renaissance architecture in Rome, and despite subsequent alterations, the church has largely retained its Sistine form to this day.

The architect or architects responsible for the design of the church remain uncertain, though Giorgio Vasari attributed the project to Baccio Pontelli, a Florentine architect. Modern scholars, however, suggest the involvement of Andrea Bregno, a Lombard sculptor and architect, and the differences between the façade and interior suggest that more than one architect may have worked on the project.

Sixtus IV was deeply attached to the church, visiting frequently to pray and celebrate mass, particularly on the Feast of the Nativity of the Virgin on September 6. The Pope’s involvement with Santa Maria del Popolo went beyond its renovation; he also established its connection to the Della Rovere family (his own family), commissioning various works and establishing the church as a dynastic monument. For example, Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, Sixtus IV’s nephew, commissioned a new high altar for the church, and other family members funded chapels and memorials within the basilica.

The Sistine reconstruction also symbolically replaced the evil walnut tree of Nero with the oak of the Della Rovere, a symbol of the family’s prosperity and divine protection. Papal coats of arms were placed on the façade and the vaults as emblems of eternal protection. The church thus became a symbol of the Della Rovere dynasty’s power, connecting their family to the grandeur of Rome itself.

The Julian Extension (1505–1510)

Following the election of Pope Julius II (also from the Della Rovere family) in 1503, the church became even more closely associated with his reign. Julius II, deeply devoted to the Madonna del Popolo, sought to further enhance the church’s glory by commissioning a new choir between 1505 and 1510. This project was entrusted to Donato Bramante, one of the leading architects of the High Renaissance. The choir was designed in Renaissance style, with a sail vault decorated by Pinturicchio, and stained glass windows by Guillaume de Marcillat. The choir also served as a mausoleum, housing tombs designed by Andrea Sansovino for Cardinal Girolamo Basso della Rovere and Cardinal Ascanio Sforza.

Raphael, another famous artist of the period, contributed paintings to the church, including the Madonna of the Veil and the Portrait of Pope Julius II. These works were significant votive offerings, occasionally displayed on the pillars during feast days, though they were eventually removed in 1591. In 1507, Agostino Chigi, a wealthy banker and relative of the Della Rovere family, was granted permission by Julius II to build a mausoleum in the church. This mausoleum replaced one of the chapels on the left side and was dedicated to the Virgin of Loreto, a figure promoted by the Della Rovere papacy. The Chigi Chapel, designed by Raphael, became one of the church’s most notable features, symbolizing the close connection between the basilica and the Chigi family.

Luther’s Visit

The church of Santa Maria del Popolo was also visited by Martin Luther, the famed Augustinian friar who would later initiate the Reformation. Luther’s journey to Rome, traditionally dated to 1510-1511, was part of his efforts to resolve a dispute between the Observant and Conventual branches of the Augustinian Order. Although details of his stay in Rome are scarce, it is believed that Luther may have lodged at Santa Maria del Popolo during his visit, as it was the only Augustinian monastery in Rome at the time. Luther certainly visited the church, which was a significant pilgrimage site and a favorite of the Pope.

The Parish

After the Della Rovere era, the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo no longer held its prominent role as a papal church but remained one of the most significant pilgrimage destinations in Rome. This was evident on 23 November 1561 when Pope Pius IV led a solemn procession from St. Peter’s to the Basilica to mark the reopening of the Council of Trent. During this period, construction in the Chigi Chapel progressed slowly, with the last major Renaissance addition being the Theodoli Chapel, built between 1555 and 1575, featuring elaborate stucco work and frescoes by Giulio Mazzoni.

Around the same time, the basilica became a parish church after Pope Pius IV established the Parish of St. Andrew “outside Porta Flaminia” on 1 January 1561, uniting it permanently with the Augustinian priory. The friars were entrusted with the care of the new parish, and later, Pope Pius V moved the parish seat to Santa Maria del Popolo. The parish continues to exist today, covering a large area, including the southern part of the Flaminio district, Pincian Hill, and the northern parts of the historic center near Piazza del Popolo. On 13 April 1587, Pope Sixtus V made the basilica a titular church through the apostolic constitution Religiosa, with Cardinal Tolomeo Gallio as the first cardinal priest. Pope Sixtus V also raised the basilica’s liturgical importance, appointing it as a station church in his bull of 13 February 1586, reviving the ancient tradition of the Stations of the Cross. The basilica later became part of the Seven Pilgrim Churches of Rome, replacing the Basilica of San Sebastiano fuori le mura.

In April 1594, Pope Clement VIII ordered the removal of the tomb of Vannozza dei Cattanei, mistress of Pope Alexander VI, from the basilica, as the Borgias’ memory was deemed a stain on the Church’s reputation during the papacy’s reform efforts.

Caravaggio and the Chigi Reconstruction

On 8 July 1600, Monsignor Tiberio Cerasi, Treasurer-General under Pope Clement VIII, acquired the patronage of the former Foscari Chapel in the left transept, demolishing it and constructing the new Cerasi Chapel, designed by Carlo Maderno between 1600 and 1601. This chapel was adorned with two iconic Baroque paintings by Caravaggio: The Conversion of Saint Paul and The Crucifixion of Saint Peter. These masterpieces are considered high points of Western art. Additionally, the altar was decorated with The Assumption of the Virgin by Annibale Carracci.

During the first half of the 17th century, no major construction projects occurred, although numerous Baroque funeral monuments were added to the basilica’s side chapels and aisles, including the tomb of Cardinal Giovanni Garzia Mellini by Alessandro Algardi (1637–1638). Other significant fresco cycles were created by Giovanni da San Giovanni in the Mellini Chapel and by Pieter van Lint in the Chapel of Innocenzo Cybo during the 1620s and 1630s.

The Chigi Chapel and Bernini’s Work

A new phase of construction began when Fabio Chigi, later Pope Alexander VII, became the cardinal priest of the basilica in 1652. He immediately began the reconstruction of the neglected family chapel, which was later embellished by Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The work was completed by the middle of 1657, although the final statue by Bernini was installed in 1661. Pope Alexander VII supervised extensive renovations to modernize the basilica in the Baroque style. These changes included a new façade, larger windows in the nave, added statues, frescoes, stucco decorations, a new main altar, and side altars in the transept, where the old Borgia Chapel had stood. Chigi’s coat of arms and symbols of his papacy were prominently displayed throughout, celebrating his achievements.

The basilica’s appearance was nearly finalized with the completion of Bernini’s renovations. However, during the papacy of Innocent XI, Cardinal Alderano Cybo demolished the second family chapel and built the Baroque Cybo Chapel (1682–1687), designed by Carlo Fontana. This large, domed chapel was decorated by Carlo Maratta, Daniel Seiter, and Luigi Garzi and is regarded as one of the most important sacred monuments built in the last quarter of the 17th century.

Later Developments

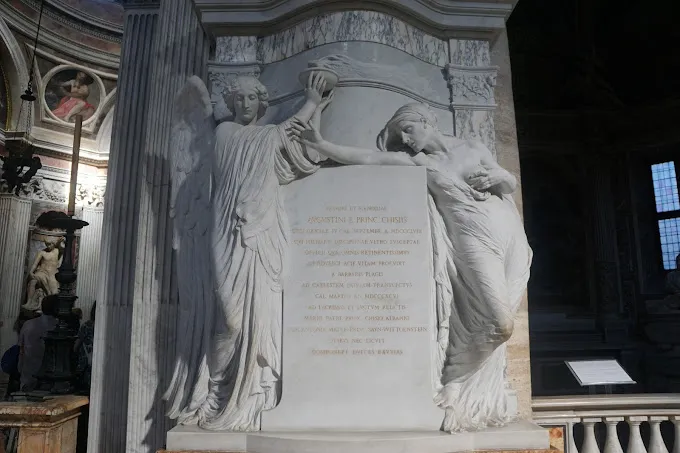

During the reign of Pope Clement XI, the basilica witnessed a joyful event on 8 September 1716 when the pope blessed a sword adorned with papal arms and sent it as a gift to Prince Eugene of Savoy, the commander of the imperial army, after his victory at the Battle of Petrovaradin in the Austro-Turkish War. The most notable 18th-century addition to the basilica was the magnificent funeral monument for Princess Maria Flaminia Odescalchi Chigi, wife of Don Sigismondo Chigi Albani della Rovere. Designed by Paolo Posi in 1772, it is often considered the “last Baroque tomb in Rome.” By this time, the church was filled with numerous tombs and artworks, leaving little space for 19th-century additions. Still, smaller changes included the restoration of the Cybo-Soderini Chapel in 1825, the redesign of the Feoli Chapel in 1857 in Neo-Renaissance style, and the installation of Agostino Chigi’s monumental Art Nouveau tomb by Adolfo Apolloni in 1915.

In 1912, Antonio Muñoz undertook a significant restoration to “restore the church to its beautiful quattrocento character,” removing many of the Baroque additions in the nave and transept.

Urban Changes and Modern Interventions

Between 1816 and 1824, the urban landscape around the basilica underwent major transformation when Giuseppe Valadier designed the monumental Neo-Classical ensemble of Piazza del Popolo, commissioned by Pope Pius VII. As part of this project, the old Augustinian monastery was demolished, its gardens appropriated, and a new, smaller Neo-Classical monastery was built. This new structure covered the entire right side of the basilica, obscuring the side chapels and wrapping around the bell tower’s base, thereby reducing the basilica’s visual prominence in the square.

Architecture Of The Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome, Italy

Architects: Andrea Bregno, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Donato Bramante, Baccio Pontelli.

Architectural Styles: Baroque architecture, Renaissance architecture.

Burials: Girolamo Basso della Rovere, Alderano Cybo.

Exterior of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo

Facade

The facade of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo was originally constructed in the early Renaissance style during the 1470s when Pope Sixtus IV oversaw the reconstruction of the medieval church. The design was later modified by Gian Lorenzo Bernini in the 17th century, though earlier depictions, such as a woodcut in Girolamo Franzini’s guide from 1588 and a veduta by Giovanni Maggi in 1625, preserve the original form. Originally, the façade featured tracery panels in the windows, spokes in the central rose window, and was free-standing, allowing for an unobstructed view of the bell tower and a series of identical side chapels on the right.

Though often attributed to Andrea Bregno, the architect of the façade remains uncertain. According to Ulrich Fürst, the architect’s design focused on perfect proportions and restrained detailing, making it one of the finest early-Renaissance church façades in Rome.

The facade is constructed from bright Roman travertine and spans two stories. The structure is accessed through three entrances, each reached by a flight of stairs, contributing to the basilica’s monumental presence. The design is simple yet dignified, with four shallow pilasters on the lower level and two pilasters flanking the upper part, with the rose window at the center. The lower-level pilasters feature Corinthianesque capitals adorned with egg-and-dart molding and vegetal motifs, while the upper-level pilasters display simpler capitals with acanthus leaves, scrolls, and palmettes. Above the side doors are triangular pediments, each bearing dedicatory inscriptions referring to Pope Sixtus IV. Above the central door, a more monumental pointed pediment is adorned with a sculpture of the Madonna and Child set in a scallop shell, surrounded by cherubs, six-pointed stars, and clouds. The frieze above the door features finely carved foliage, pecking birds, and putti holding torches and oak branches. Pope Sixtus IV’s coat of arms is prominently displayed, encircled by oak branches. These sculptural details reflect the iconographic program of the Sistine rebuilding, with the Madonna del Popolo as the central motif, symbolizing heavenly light and abundance, intertwined with the Della Rovere family emblem.

Bernini later made Baroque modifications to the façade, adding the two halves of a broken segmental pediment on the sides of the upper level, replacing the original volutes, and incorporating oak garlands. He also added the Chigi family symbols, including flaming torches and six mountains. The original pediment was decorated with the coat of arms of Pope Sixtus IV, but only the upper portion of the shield remains.

Inscriptions

Two significant inscriptions appear on either side of the main entrance, quoting the bulls of Pope Sixtus IV. The first, dated 7 September 1472, begins with the words Ineffabilia Gloriosae Virginis Dei Genitricis and grants plenary indulgence and remission of sins to the faithful who attend the church on specific feast days dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The second, dated 12 October 1472, begins with A Sede Apostolica sunt illa benigno favore concedenda and confirms the perpetual plenary indulgence granted on those feast days, alongside other indulgences previously granted by past popes.

These inscriptions are exemplary of the Sistine style of ‘all’antica’ lettering, a revived ancient Roman monumental inscriptional style, which was adapted into the Renaissance. This style was popularized by Andrea Bregno, who used it in his funeral monuments. Additionally, smaller plaques near the right door commemorate indulgences granted by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 and Pope Sixtus V’s inclusion of Santa Maria del Popolo among the Seven Pilgrim Churches of Rome in 1586.

The Dome

The dome of Santa Maria del Popolo, built between 1474 and 1475, was the first octagonal Renaissance dome placed above a rectangular crossing and elevated on a high tambour. It was a groundbreaking architectural feature at the time, with no direct precedent except for Filarete’s utopian city drawings for Sforzinda, which were never constructed. The dome became a visual anomaly in Rome’s skyline but later served as a prototype for other domes in the city and beyond. The dome’s placement was symbolic, as it centered on the miraculous icon of the Madonna del Popolo.

The dome is constructed from a mix of tuff blocks, bricks, and mortar, covered with lead sheets. There is a thin inner brick shell, likely added later to provide a suitable surface for frescoes. The dome is capped with an elegant globe and cross finial. The high brick tambour is punctuated by eight arched windows, which originally featured stone mullions like other openings in the church. The entire structure rests on a low square base.

Bell Tower

The 15th-century bell tower is positioned at the end of the right transept. It was later incorporated into the Neo-Classical monastery that partially covers its structure. The tall, brick tower was built in a Northern Italian style, which was atypical for Rome but suited the tastes of the Lombard congregation. Its conical spire is constructed from petal-shaped clay bricks and surrounded by four cylindrical pinnacles with conical caps. The pinnacles feature two rows of blind arcades with cusped brick arches. The spire is crowned with a ball and cross finial and a weather vane. The top of the tower bears a strong resemblance to the bell tower of the Basilica of San Zeno in Verona. The rectangular tower is articulated by stone cornices, and the top floor is equipped with large arched windows on all sides. Only remnants of the original stone mullions and ornamental parapets remain, except for the eastern side, where the mullion is intact, featuring a biforate window with Tuscan pillars and a quatrefoil.

A later addition to the tower is a circular clock on the southern side, which was installed in the 18th century and placed lower down than its original position. A second row of arched windows on this level was walled up in the late 17th century.

Doors of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo

The Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo features three intricately designed wooden doors adorned with bronze reliefs by Calabrian sculptor Michele Guerrisi, created in 1963. The main door panels depict scenes from the Passion of Christ, including the Descent from the Cross, the Resurrection, and moments such as Jesus meeting his mother and his agony in the garden. The side doors feature Biblical phrases, with the left door panels highlighting themes like wisdom, the Blood of Christ, prayer, and the purification of the faithful, while the right door panels emphasize evangelization, readiness, sacrifice, and divine commands. These panels include depictions of angels with symbols like the chalice, cross, and dove, each accompanied by meaningful phrases from scripture, such as “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” and “Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations.”

Interior of Santa Maria del Popolo Basilica

Counterfacade

The decoration of the counterfaçade was part of the 17th-century Berninian reconstruction of the church. The design features a simple architectural style with a marble frame around the monumental door, a dentilled cornice, and a segmental arched pediment. A dedicatory inscription commemorates the rebuilding of the ancient church by Pope Alexander VII, initiated as Fabio Chigi, Cardinal Priest of the basilica, and its consecration in 1655.

The rose window is supported by two stucco angels sculpted by Ercole Ferrata (1655-58), under Bernini’s guidance. The angels are positioned with one holding a wreath. The lower part of the counterfaçade features several funeral monuments.

Nave

Santa Maria del Popolo is a Renaissance basilica with a nave, two aisles, and a transept with a central dome. The nave and aisles have four bays, covered with cross-vaults. Four piers on each side support the arches separating the nave from the aisles, with travertine semi-columns that help support the arches and vaults.

Bernini preserved much of the original 15th-century architecture, adding a strong stone cornice and embellishing the arches with pairs of white stucco statues of female saints. The saints, many early Christian figures, are accompanied by their names in gilt letters on the spandrels. The cross-vaults were left undecorated. The keystones in the nave and transept bear the coats of arms of Pope Sixtus IV, and the Della Rovere escutcheons appear in the first and last arches of the nave.

The nave is lit by two rows of large, segmental arched clerestory windows. Before Bernini’s reconstruction, the windows were the same as those on the façade and bell tower. The triumphal arch at the end of the nave is decorated with a stucco group created during the reconstruction, featuring the papal coat of arms flanked by angelic Victories holding palm branches.

Pairs of Saints in the Nave

Bernini originally planned to populate the spaces between the windows and arches of the nave with statues of kneeling angels but ultimately chose to place statues of female saints, directing the viewer’s attention toward the image of the Virgin at the main altar. The statues, likely designed by Bernini and executed by his workshop, are arranged symmetrically on both sides of the nave. On the left side, the first arch features Saint Clare with a monstrance and Saint Scholastica with a book and dove (by Ercole Ferrata), the second arch shows Saint Catherine with a palm branch, crown, and broken torture device, and Saint Barbara with a palm branch and tower (by Antonio Raggi), the third arch displays Saint Dorothy with a cherub holding a basket of fruits and Saint Agatha with a cherub and palm branch (by Giuseppe Perone), and the fourth arch portrays Saint Thecla with a lion and Saint Apollonia with a bear (by Antonio Raggi). On the right side, the first arch includes Saint Catherine of Siena with a crucifix and Saint Teresa of Ávila with her heart pierced (by Giovanni Francesco de Rossi), the second arch features Saint Praxedes with a sponge and vessel and Saint Pudentiana with a cloth and vessel (by Paolo Naldini and Lazzaro Morelli), the third arch depicts Saint Cecilia with an organ and angel, and Saint Ursula with a banner (by Giovanni Antonio Mari), and the fourth arch shows Saint Agnes with a lamb and palm branch and Saint Martina with a lion and palm branch (by Giovanni Francesco de Rossi).

Transept

The transept mirrors the architectural style of the nave, with cross-vaults, half-columns, and Baroque details. The transept arms end in semicircular apses rebuilt by Bernini. The side altars, located in the transept, are decorated with various marbles and feature triangular pediments, Corinthian pilasters, and classical friezes. These altars are supported by four marble angels, sculpted by artists including Antonio Raggi, Ercole Ferrata, Giovanni Antonio Mari, and Arrigo Giardè.

Inscriptions above the transept chapels refer to Pope Alexander VII’s nephews, Flavio and Agostino Chigi, as founders of the altars, which were consecrated by the pope.

Altar of the Visitation

The altarpiece in the right transept was painted in 1659 by Giovanni Maria Morandi, depicting the Visitation. Untraditionally, Morandi shows Elizabeth inviting Mary into her home, rather than the typical moment of their meeting. The painting features monumental Roman architecture in the background, adding a distinctly Roman context to the biblical narrative. The marble statues of angels framing the altar are attributed to Ercole Ferrata and Arrigo Giardè.

Santissima Pieta (Pieta of Salerno)

Originally called Cappella della Santissima Pietà, this chapel was dedicated to the funeral monument of Archbishop Pietro Guglielmo Rocca. The altarpiece, once by Jacopino del Conte, is now housed in the Musée Condé in Chantilly. The name “Pietà” refers to the altarpiece’s depiction of Christ’s deposition into the tomb.

Altar of the Holy Family

The altar in the right transept features an altarpiece painted by Bernardino Mei in 1659. The scene depicts the Holy Family, emphasizing the impending mission of Jesus, with symbolic elements like the chalice and the skull representing triumph over evil. The marble statues of angels supporting the altar are attributed to Giovanni Antonio Mari (left) and Antonio Raggi (right).

Organ Lofts

The right organ loft houses a case that dates back to 1499-1500, designed by Stefano Pavoni. During Bernini’s reconstruction, the organ was rebuilt by Giuseppe Testa. The left organ loft has a modern organ built in 1906. The organ lofts, designed by Bernini, feature rich decoration with stucco angels and cherubs, and incorporate symbols of the Chigi family, such as the oak tree and mountain and star.

Dome

The dome, designed with a light, thin structure to support painted decoration, is illuminated by eight semicircular windows. The marble revetment and Corinthian pilasters on the tambour have a Berninian style. The triumphal arch of the chancel is adorned with painted stucco, displaying the coat of arms of Cardinal Antonio Maria Sauli.

Apse

Designed by Donato Bramante, the apse houses the oldest stained glass window in Rome, made by Guillaume de Marcillat. The vault is decorated with frescoes by Pinturicchio, including the Coronation of the Virgin. The tombs of Cardinals Ascanio Sforza and Girolamo Basso della Rovere are also found in the apse, sculpted by Andrea Sansovino.

Furniture

While much of the furniture in the basilica is modern, including pews and the new altar, a few Baroque pieces remain. These include two holy water stoups made of colored marble and six wooden confessionals located between the nave and aisles. These confessionals vary in design, with some featuring the Chigi family’s symbols of mountains and oak branches, while others depict the Madonna and Child.

Side Chapels and Monuments of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo

The Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo houses a collection of side chapels and monumental tombs, each contributing to the rich artistic and architectural heritage of the church. The Della Rovere Chapel, the first on the right aisle, was furnished by Cardinal Domenico della Rovere in 1477, featuring a main altar-piece by Pinturicchio. Other chapels include the Cybo Chapel, rebuilt by Cardinal Alderano Cybo in the late 17th century, and the Basso Della Rovere Chapel, decorated by Pinturicchio’s school. The Costa Chapel, completed in the late 15th century, houses works by Gian Cristoforo Romano, while the Montemirabile Chapel, transformed into the basilica’s baptistery in 1561, contains notable baptismal fonts and tombs. The Chigi Chapel, designed by Raphael and later completed by Bernini, stands out for its rich artistic significance, while the Mellini Chapel, dedicated to Saint Nicholas of Tolentino, contains works by Alessandro Algardi and Pierre-Étienne Monnot. The Cybo-Soderini Chapel features frescoes by Pieter van Lint, and the Theodoli Chapel, with its Mannerist decor, offers a striking example of Giulio Mazzoni’s work. The Cerasi Chapel is home to two iconic Caravaggio paintings, Crucifixion of St. Peter and Conversion on the Way to Damascus, while the Feoli and Cicada Chapels offer simpler, 17th-century decorations.

Notable monuments in the basilica include the Baroque tomb of Maria Eleonora Boncompagni, designed by Domenico Gregorini, and the macabre Gisleni monument by Giovanni Battista Gisleni. Other significant tombs include those of Maria Flaminia Odescalchi Chigi, a stunning work by Paolo Posi, and the Mannerist tomb of Cardinal Gian Girolamo Albani, designed by Giovanni Antonio Paracca. The tomb of Cardinal Ludovico Podocataro is a masterpiece of Roman Renaissance sculpture, while the monument of Cardinal Bernardino Lonati reflects the influence of Andrea Bregno’s design style. These monuments, along with the chapels, contribute to the basilica’s status as a key architectural and artistic site in Rome.

Feast Day

Feast Day: 08 December.

The feast day of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo is celebrated on December 8, in conjunction with the Feast of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary. This feast honors the Basilica’s dedication to the Virgin Mary and is a significant celebration for the church, as it is one of the most important Marian churches in Rome.

Church Mass Timing

Monday : 6:00 PM

Tuesday : 6:00 PM

Wednesday : 6:00 PM

Thursday : 6:00 PM

Friday : 6:00 PM

Saturday : 6:30 PM

Sunday : 10:30 AM , 12:00 PM , 6:30 PM.

Church Opening Time:

Monday : 8:30 am – 12:00 pm, 4:00 pm – 6:00 pm

Tuesday : 8:30 am – 12:00 pm, 4:00 pm – 6:00 pm

Wednesday : 8:30 am – 12:00 pm, 4:00 pm – 6:00 pm

Thursday : 8:30 am – 12:00 pm, 4:00 pm – 6:00 pm

Friday : 8:30 am – 12:00 pm, 4:00 pm – 6:00 pm

Saturday : 8:30 am – 12:00 pm, 4:00 pm – 6:00 pm

Sunday : 4:30 pm – 6:00 pm

Contact Info

Address :

Piazza del Popolo, 12, 00187 Roma RM, Italy.

Phone : +39 06 4567 5909

Accommodations

Connectivities

Airway

Leonardo da Vinci International Airport (FCO), to Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome, Italy distance between 42 min (29.1 km) via A91.

Railway

Basilica of Saint Mary of the Angels and Martyrs P.za della Repubblica, to Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome, Italy distance between 10 min (3.2 km) via Viale del Muro Torto.