Introduction

The Basilica of San Zeno, also known as San Zeno Maggiore or San Zenone, is a prominent Catholic church located in the San Zeno district of Verona, Italy. It stands as one of the finest examples of Romanesque architecture in northern Italy and holds a significant place in the city’s religious and cultural history. The basilica’s long and storied past is intertwined with the legacy of Saint Zeno of Verona, the patron saint of the city. The church’s origins date back to the early Christian period, built over the site of at least five earlier religious buildings. Tradition holds that the first church on the site was constructed on the tomb of Saint Zeno, who died between 372 and 380 AD. The first church was likely a modest structure, but as the veneration of Saint Zeno grew, it became clear that a grander church was needed. The church underwent significant rebuilding in the early 9th century under the direction of Bishop Ratoldo and the King of Italy Pepin. This reconstruction was prompted by the desire to honor Saint Zeno’s body with a fitting resting place. The archdeacon Pacifico is also said to have contributed to the construction, and the church was consecrated on December 8, 806. The body of Saint Zeno was then transferred to the newly completed crypt on May 21, 807.

Throughout its history, the basilica endured several hardships, including significant damage during the Hungarian invasions between 899 and 933. As a result, Bishop Raterio initiated further reconstruction in 967. The church was rebuilt in the Romanesque style around the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries, although progress was delayed by the devastating earthquake in Verona in 1117. By 1138, much of the current structure had been completed, and further renovations and additions continued over the centuries. Despite the changes, the church has retained its original medieval layout. The Basilica of San Zeno is renowned for its artistic treasures. Among its most famous works is the altarpiece by Andrea Mantegna, which depicts the Saint Zeno. The church also boasts the bronze panels of the main portal, as well as the striking rose window, known as the “Wheel of Fortune,” designed by the stonemason Brioloto de Balneo. These masterpieces, along with the church’s historic ambiance, have inspired generations of poets and artists, including Dante Alighieri, Giosuè Carducci, Heinrich Heine, Gabriele D’Annunzio, and Berto Barbarani.

In recognition of its historical and spiritual significance, the Basilica of San Zeno was elevated to the status of a minor basilica in 1973. Today, it serves as the seat of a parish within the Verona Centro Vicariate, continuing its mission as a place of worship and pilgrimage. Additionally, the church is famously associated with the legend of the marriage of Romeo and Juliet, as it is traditionally believed to be the site of their wedding in Shakespeare’s iconic play. With its stunning Romanesque architecture, rich history, and cultural influence, the Basilica of San Zeno remains one of Verona’s most significant landmarks and a cherished symbol of the city’s religious and artistic heritage.

St. Zeno of Verona, who passed away around 371–380 AD, is the central figure behind the Basilica of San Zeno. According to legend, Theodoric the Great, the king of the Ostrogoths, first erected a small church above his tomb along the Via Gallica. The present basilica and monastery, however, began construction in the 9th century under the leadership of Bishop Ratoldus, with King Pepin of Italy contributing to the translation of St. Zeno’s relics to the new church. This church was damaged during the Magyar invasion of the early 10th century, and Zeno’s body was temporarily moved to the Cathedral of Santa Maria Matricolare. On May 21, 921, it was returned to the crypt of the basilica. Later, in 967, Bishop Raterius, with the support of Holy Roman Emperor Otto I, commissioned the construction of a new Romanesque church.

Early Christian Origins and Development

Christianity arrived early in Verona, which, as a strategic road junction, would have seen the passage of soldiers from Rome and Palestine. The city’s first bishop, Euprepius, was appointed in the first half of the 3rd century, with Zeno of Verona, who died around 372–380, following shortly after. Tradition holds that Zeno was buried near the future site of the basilica. The Veronese notary Coronato, writing in the late 7th century, mentions that a church was erected above Zeno’s tomb, and it was enlarged after a miracle recounted by Saint Gregory the Great in the 6th century. According to the story, the Adige River flooded Verona, submerging the church but not entering it, offering sanctuary to many people within.

The church underwent several restorations during this period, including significant work done in the 6th century, when Byzantine-style columns and carvings were integrated into the structure. These artifacts, now housed in the chapel of San Benedetto and the bell tower, suggest that Theodoric the Great might have contributed to the church’s reconstruction. The city fell under the control of the Lombards in the 6th century after the fall of the Gothic Kingdom, and St. Zeno’s church continued to house the saint’s remains, even as the Lombards adopted Arianism. King Desiderius of the Lombards made donations to the church, including the creation of the Domus Sancti Zenonis.

The 9th Century and King Pepin’s Contributions

In 804, the church suffered severe damage, and it was reported that it had been almost completely destroyed by fire, possibly caused by unrest among the local Frankish or Arian populations. Around this time, King Pepin of Italy, accompanied by Bishop Ratoldus, recognized the need to build a grander church for St. Zeno’s relics. They decided to construct a larger church with a crypt to house the saint’s body in a more dignified manner. The new building was consecrated on December 8, 806, and the saint’s relics were transferred to the crypt on May 21, 807, in a grand ceremony attended by the king and local bishops.

The new structure was designed with an apse oriented from south to north, resembling that of the nearby church of San Procolo. The crypt, which was meant to be an underground chamber, was built to hold the saint’s remains, while the rest of the church was elevated above. The church was adorned with precious gifts from King Pepin, including gold and silver vessels and gem-encrusted Gospels. The construction of a Benedictine monastery was also planned, and the first recorded abbot, Leo, served in 833.

10th Century to 11th Century: Reconstruction and Fortification

The 10th century brought its own set of challenges. The Hungarian invasions of the late 9th and early 10th centuries severely damaged the church, as it was located outside Verona’s defensive walls. Some sources suggest that during these raids, St. Zeno’s relics were moved to safety in the Cathedral of Santa Maria Matricolare. After the cessation of the Hungarian raids, Bishop Raterius undertook the reconstruction of the church. He received funding for the project from Emperor Otto I in exchange for hosting the emperor in Verona in 967.

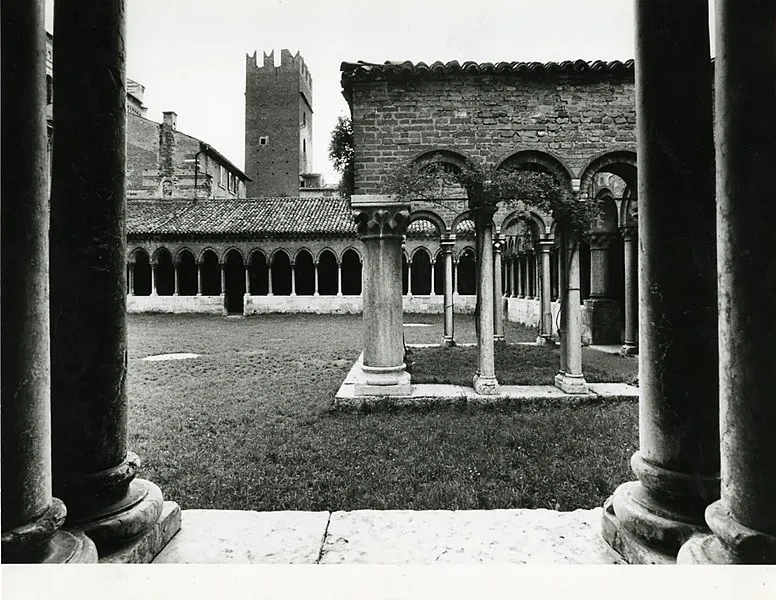

However, Raterius was soon embroiled in controversy regarding the use of funds. He defended himself in the Apologetico, claiming that the money was used to reform the local clergy, particularly to end concubinage among priests. The reconstruction followed the Romanesque style that was becoming prominent in Verona at the time, with a three-nave design, a raised central nave, and a crypt below. The new church was smaller than the present structure but had a similar width. The work, which included three apses, was completed by the mid-11th century. The crypt that still exists today likely dates from this period. The walls of the eastern side of the church, near the bell tower, show traces of brickwork and a saw-tooth band that marks the cornice. This period also saw the completion of certain elements like the cloister, built with a mixture of tuff and brick, still visible today.

11th Century and the Construction of the Bell Tower

In the 11th century, the church underwent further improvements. Around 1045, Abbot Alberico initiated the construction of the bell tower, as documented by an inscription on the tower’s base. By the time of Alberico’s death in 1067, the tower had reached about half of its current height, and it is likely that the mullioned windows had already been added. During his abbacy, Alberico also constructed a monks’ tomb in the cloister, a red marble tomb that is adorned with a large cross relief.

Renovation of the Church of San Zeno and the Earthquake of 1117

At the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries, a major renovation project was undertaken to expand and restore the Church of San Zeno. The goal was to enlarge the structure by adding a new section in front of the original façade, which today corresponds to the first bay of the church. Additionally, renovations were planned for the old longitudinal walls, both of the major and minor naves. The proposed new construction, as seen in the remaining elements today, was to feature finely squared tuff facings, projecting pilasters, a marble gallery with small arches supported by twin columns, and a cornice with arches and double lintels. The intricate carvings were particularly visible in the frieze sculpted in white marble.

This ambitious restoration project was well underway when a devastating earthquake struck Verona in 1117, causing significant damage to the city and its buildings. By that point, the expansion was nearly complete, and the right nave’s side walls had already begun to be renovated. Despite the destruction caused by the earthquake, the work on the church continued, albeit more modestly. Efforts were made to reuse materials from the collapsed sections to rebuild the church. Between 1117 and 1138, the damaged walls were reconstructed, with the main nave being surrounded by new bundle pillars. By 1138, the restoration was complete, and the new porch of the façade could already be seen, as confirmed by an inscription located on the southern side of the nave near the facade.

The bell tower also saw significant progress during this period. The inscription on the southern wall of the nave commemorates the completion of the bell tower’s restoration in 1120, with the addition of a first bell tower. In 1138, the church expansion, which included at least one additional bay towards the west, was officially finished. In parallel to the work on the church, the priest Gaudio was responsible for the restoration of the abbey’s cloister, completed in 1123. The cloister renovations were significant enough to suggest a full rebuild rather than a simple restructuring. As attested by inscriptions, Gaudio also contributed to the abbey’s daily functioning, ensuring that a constant supply of oil was provided for the cloister lamp.

12th Century and 13th Century Developments

From 1138 to 1187, during the tenure of Abbot Gerardo, the focus shifted to the completion of the bell tower and the production of bells. Although no significant works were carried out on the church itself during this period, an inscription from 1178 on the southern side of the church suggests that Abbot Gerardo’s efforts were also directed towards the continued enhancement of the church, including its enlargement. The cloister columns and capitals, which show no signs of reused fragments, demonstrate the thorough renovation completed under Gaudio’s direction. These renovations were part of a larger pattern of improvements to the abbey, which included the construction of the large crenellated tower, begun in 1145 as a defensive structure for the basilica. The basilica’s external location made it vulnerable to attack, and this tower served as an important bulwark until the Scaligeri incorporated the abbey into the city’s defensive walls.

During the late 12th century, a new chapter in the church’s artistic development began. In 1189, Abbot Ugone commissioned a sculptor named Brioloto de Balneo to work on the church, creating the “Wheel of Fortune” rose window. This rose window, located on the façade of the church, was decorated with six statues representing the different phases of human life. Brioloto’s work, in collaboration with the stonecutter Adamino da San Giorgio, is also evident in the access arches to the crypt and the upper frames of the façade. By the early 13th century, the basilica had expanded to include a baptistery, constructed after the Canons of the Cathedral granted permission for baptisms at San Zeno in 1194. Other additions from the period include the columns and statues that now decorate the interior of the church, many of which were produced by anonymous sculptors.

14th and 15th Century Transformations

Between the late 13th and early 14th centuries, Verona experienced a surge in religious construction and renovation, and San Zeno was no exception. The basilica, still dominated by the apse from the 10th century, required a major expansion. The old apse was considered too small and narrow for the expanding church, and so work began to enlarge it around 1300. This first phase of enlargement was followed by additional work at the end of the 14th century, completed by the architect Giovanni da Ferrara, who began work on 24 March 1386 and finished in 1398. The apse, now in Gothic style, was adorned with frescoes by Abbot Pietro Paolo Cappelli and Abbot Pietro Emilei, the latter placing his noble coat of arms in several prominent locations. Despite these improvements, the abbey faced significant decline throughout the 14th century, with dwindling numbers of monks and reduced financial resources, partly due to pillaging by the Scaligeri. In 1405, Verona fell under Venetian control, and the abbey transitioned to a period of commendatory abbots, beginning with the appointment of Marco Emilei in 1425.

Renaissance and Later Transformations

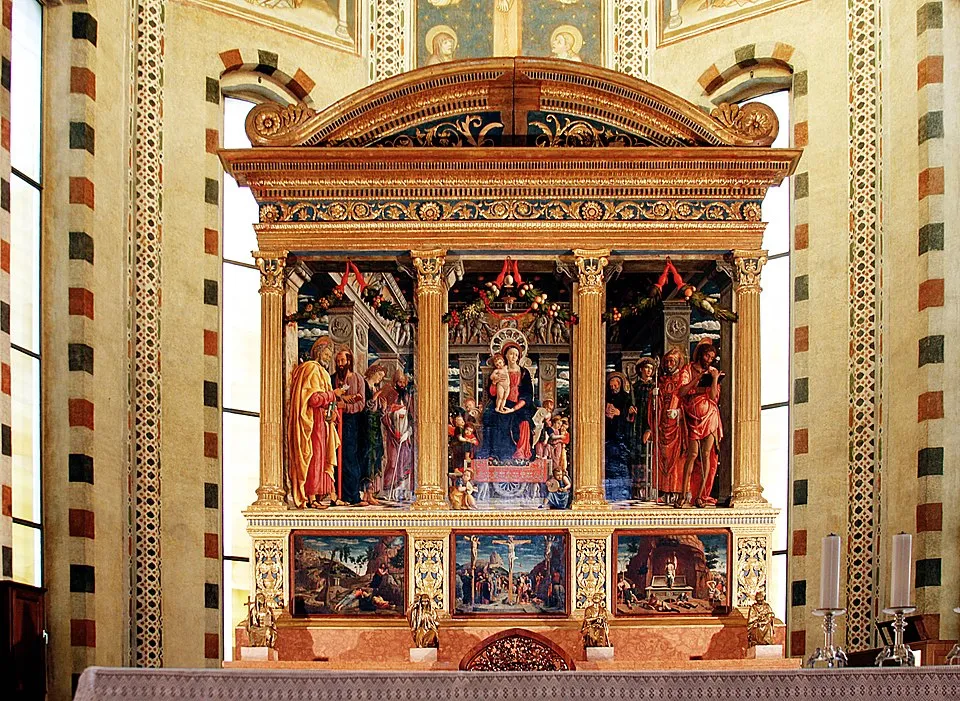

The Renaissance ushered in a new era of artistic and architectural transformations, and the basilica of San Zeno was no exception. Major works took place at the beginning of the 16th century, including the demolition of dividing piers and the relocation of the choir. The church was adapted to fit the new taste of the era, and a new high altar was constructed under the triumphal arch. One of the most significant commissions during this time was the San Zeno Altarpiece, painted by Andrea Mantegna for the main altar. In addition to the high altar, a large tabernacle was also constructed, and various renovations took place in the upper church, including the restoration of the sacristy by Abbot Jacopo Surain in the late 15th century. The 16th century also saw the introduction of Renaissance-style elements in the basilica, including the completion of a new side altar in 1535 and the removal of the old altar to make way for the current one.

17th Century and the Suppression of the Abbey

The 17th century was marked by further changes, including the demolition of part of the abbey complex. The religious community experienced a period of great decline, with the suppression of the abbey in 1770. Much of its real estate was transferred to the Civil Hospitals of Verona, while its book collection became the foundation of the city’s library. The early 19th century saw further changes to the abbey complex, including the discovery of the relics of Saint Zeno in 1838. The relics were exhumed and placed in a gilded wooden urn for safekeeping. Later in the century, the church underwent restoration work, including the reopening of stained glass windows and the restoration of frescoes.

In the 20th century, significant efforts were made to preserve the basilica’s heritage. Between 1927 and 1931, the Mantegna altarpiece was relocated, and the church underwent further restoration, including the creation of new stained glass windows. The 1938 restoration focused on improving the hygienic conditions of the crypt and ensuring the proper preservation of Saint Zeno’s tomb. Through centuries of destruction, rebuilding, and transformation, the Basilica of San Zeno has remained a symbol of Verona’s rich architectural and religious heritage, continuing to serve as a place of worship and a testament to the city’s cultural resilience.

Architecture of Basilica of San Zeno Maggiore, Verona, Italy

Architectural Style : Romanesque architecture.

External View

The side view of the Basilica of San Zeno reveals the use of different materials that reflect the building’s construction phases. The oldest part of the church is characterized by alternating terracotta and tuff stones, which are evident on the southern side, indicating the initial phase. The section closest to the façade is made exclusively of tuff, signaling the later expansion of the basilica. The church’s exterior is a prime example of Romanesque architecture in northern Italy. The façade, constructed from tuff, was completed during the last phase of expansion in the early 12th century. Some elements of the façade, such as the portal and porch, were repurposed from the earlier structure. The prominent central rose window, known as the “Wheel of Fortune” due to its symbolic meaning, is one of the most famous features of the church.

Facade

The façade of the basilica can be divided into three distinct sections that mirror the internal layout: the two lateral parts corresponding to the minor naves, and the central section that corresponds to the major nave. The masonry of the lateral sections is made of tuff blocks, while the gallery is crafted from a stone similar to that used on the southern side. The cornice beneath the slope is supported by simple brackets that hold double-arched arches with thin, low reliefs. Above this cornice, there is a frieze sculpted by Adamino, replacing the original one. A small bas-relief located on the right side of the façade depicts Christ with a cruciferous halo, with a saint and a headless abbot holding a model of the church and bell tower. This bas-relief is thought to represent the church’s design during the expansion, including the bell tower begun in 1046 by Abbot Alberico. The central part of the façade consists of two sections: the lower one, which houses the large rose window (“Wheel of Fortune”), the portal, and the porch; and the upper one, which features the rose window and the tympanum. The division between these two areas is marked by a frame of saw-tooth arches, interrupted by the rose window.

The Rose Window and Pediment

The rose window, designed by Brioloto de Balneo, is decorated with six statues symbolizing the alternating phases of human life or Fortune, hence its name “Wheel of Fortune.” The rose window is divided into twelve sectors by pairs of red marble columns, and at the center is a hub, crowned with twelve lobes. Surrounding it is a three-step ring of white and blue marble, with six figures representing the changes in destiny caused by Fortune. The inscriptions on the hub of the wheel explain the symbolism, with one reading: “En ego Fortuna moderor mortalibus una. / Elevo, depono, bona cunctis vel mala dono,” and another, “Induo nudatos, denudo veste paratos; / in me conidit si quis, derisus abibit.” The pediment, which marks the top of the central nave, is made of white marble, contrasting with the tuff and stone façade of the church. In 1905, Massimiliano Ongaro discovered graffiti on the tympanum representing the Last Judgment, attributed to Brioloto and Adamino da San Giorgio. The scene depicts Christ enthroned at the center, flanked by angels, Mary, and St. John. Below, the elect and the reprobate are shown with angels guiding some souls to heaven and others to damnation.

The Porch

The porch of the basilica was designed by the master Niccolò in the 12th century, though some alterations were likely made later. It is simple in form, consisting of a single canopy supported by two crouched telamons. On the arch above, a bas-relief of the Lamb and the blessing hand of God is displayed, accompanied by an inscription: “The right hand of God blesses the people who enter to ask for holy things.” The base of the porch features two lions holding columns, symbolizing guardianship of the church. The porch also contains three types of representations: sacred scenes from the life of St. Zeno, political scenes marking the birth of the medieval municipality of Verona, and profane scenes depicting the months and corresponding trades. The lunette above the porch features a bas-relief commemorating the consecration of the medieval municipality in 1138, showing St. Zeno trampling the devil, symbolizing the pact between the feudal nobility and the emerging bourgeoisie.

High Reliefs on the Porch

The high reliefs on the sides of the portal include 18 scenes carved in the 12th century. These reliefs, divided between the left and right sides, depict both sacred and profane subjects. The left side, attributed to master Guglielmo, portrays scenes from the New Testament, while the right side, by master Niccolò, includes scenes from Genesis and the life of King Theodoric the Great. Some of the reliefs on the right side are marked by a sculpted inscription praising Niccolò. One of the most notable features on the left side is a relief depicting a female figure under an arch, with the inscription “MATALIANA.” While the identity of this figure is debated, some suggest it could represent a benefactress of the abbey or even Matilda of Canossa.

The Portal

The basilica’s main entrance is adorned with a famous bronze portal consisting of 73 panels, each depicting various scenes. These panels are arranged without apparent symmetry, and the larger panels (48 in total) depict scenes from both the Old and New Testaments, with four depicting the miracles of St. Zeno. Smaller rectangular panels depict individual figures, while other panels are intricately worked with openwork designs. The bronze portal is considered one of the most interesting examples of its kind in Italy, despite appearing disorganized and worn due to time and theft. The panels are believed to have been made by at least three different masters over time, with the earliest panels, depicting scenes from the Old Testament, dating back to the first half of the 11th century. These panels were likely part of the older church structure before being incorporated into the larger portal during the church’s expansion in the 12th century.

Southern Flank

The southern flank of the Basilica of San Zeno presents a fascinating mix of architectural techniques and styles, reflecting the different phases of construction and expansion that the church underwent over the centuries. The oldest part of the southern side, completed around 1120, is primarily made of bricks. This section includes the apse and extends up to the buttress. The brickwork is characteristic of early Romanesque construction. The intermediate section of the southern wall exhibits a distinctive use of alternating rows of tuff blocks and clay bricks. This technique creates a visually striking effect of two-tone white and red bands, a hallmark of the Veronese Romanesque style. This style can also be found in other churches in Verona, such as in the Church of Santo Stefano. Additionally, the central nave’s side wall also features these two-tone bands, though it appears more homogeneous. The completion of this section of the wall is generally dated to 1138.

The final section, closest to the facade, is constructed entirely of tuff, believed to be from the church’s last major expansion in the 13th century. This expansion, carried out under the direction of Adamino and Brioloto, significantly enlarged the church to its current dimensions. On the eastern side of this southern flank, near the facade, there is a long inscription commemorating Abbot Gerardo, who oversaw the expansion works, as well as Martino, a master bricklayer. Just above this inscription, within a niche, is a fresco depicting the Madonna and Child in half-length. This fresco, created in the second half of the 12th century, has unfortunately been poorly restored in the 20th century, which has affected its condition. This mixture of construction techniques and historical elements on the southern flank offers a glimpse into the architectural evolution of the Basilica of San Zeno, from its Romanesque beginnings to its later expansions.

Apse Area

The apse area of the Basilica of San Zeno is a significant feature of the church’s architectural layout. The basilica culminates in the northern section with two apses: a smaller one on the left and a larger one at the center, with the one on the right being incorporated into the buildings of the ancient convent and visible only from the inside. The two visible apses are from different historical periods, reflecting the church’s evolving architecture. The smaller apse on the left is believed to date back to the 9th century, during the time of Raterio and Pipino, when the original construction of the basilica took place. This attribution is supported by the work of historian Luigi Simeoni. On the other hand, the larger apse, situated in the center, was rebuilt later, though it was once thought to have undergone further modification during the time of the Emilei abbots between 1399 and 1430. However, the discovery of the factory journal has clarified that the renovation works for the larger apse were actually carried out between 1386 and 1398, during the tenures of abbots Ottonello, Jacopo Pasti, and Pietro Paolo Cappelli.

Architecturally, the external appearance of the smaller apse is quite simple, primarily constructed of bricks. In contrast, the larger apse exhibits the distinctive Veronese Romanesque style, characterized by alternating rows of tuff and terracotta. These elements serve to disguise the apse’s inherently Gothic structure. This Gothic style is more apparent on the inside, where certain architectural elements stand out. Notably, the pointed triumphal arch, the cross vault with protruding ribs, and the high windows that end in pointed arches all highlight the apse’s Gothic design, reflecting the artistic trends of the time.

Bell Tower of San Zeno

The bell tower of the Abbey of San Zeno, seen from Piazza San Zeno, stands as a symbol of architectural evolution, built on top of an earlier structure from the 8th-9th centuries. The current bell tower is the product of a long construction history. From an inscription, we learn that construction began in 1045 under Abbot Alberico. After his death in 1067, the tower had reached about half of its current height. The tower’s construction was completed around 1178, thanks to the work of “Master Martino,” who was commissioned by Abbot Gerardo. The building project faced interruptions, including the earthquake of 1117, which led to necessary restorations in 1120. The tower rests on a massive rectangular plinth made of living stone, with the east and west sides measuring 8.25 meters and the north and south sides at 8.23 meters. The plinth stands approximately 7 meters above the ground. The stone continues above the base, notably in the corners and central pilaster strips, while the space between these features an alternating pattern of tuff and terracotta courses. This technique, also seen in the church’s perimeter walls, contributes to the bell tower’s characteristic two-tone color, a hallmark of the Veronese Romanesque style.

Each side of the bell tower is divided horizontally into four unequal orders by frames with corbels, simple tuff arches, and superimposed saw-toothed terracotta courses. The first two frames feature a single saw-toothed band, the third has two, and the fourth has four. The western side features a rectangular access door, similar to other contemporary bell towers. Notably, various reused elements are incorporated into the design. For instance, a Roman sculpture of a standing man with a Phrygian cap can be found above the second frame, while a small marble head and a winged genius sculpture are situated higher up on the tower’s facade.

The bell tower is distinguished by two superimposed orders of triple lancet windows on each face. The central opening in each set of windows is slightly smaller than the two lateral ones. All the arches are round, made of tuff blocks with a brick ring containing intertwined arches. Most of the columns, capitals, and cushions are simple in design, though some feature leaf decorations, and nearly all capitals contain a flower at the center of the abacus. In the lower order, the columns are without bases, except for one, while the capitals are predominantly made from Greek marble, with one column made of bloodstone. Four of the eight cushions are also crafted from Greek marble. Since 1498, the bell tower has housed six bells, with the largest, cast in 1423, weighing nearly a ton. This bell has a diameter of over one meter and produces a G flat note. The oldest bells include the small octagonal “del figar,” which lacks any inscriptions, and two bells from 1149, cast by the founder Gislimerio under the commission of the priest Aldo. These bells were unfortunately melted down in 1755 by Abbot Rezzonico, but their inscriptions have been preserved through the records of Giovanni Battista Biancolini.

The barrel of the bell tower ends with smooth tuff mouldings, and at each corner stand four brick pinnacles, each featuring a double arch on the face. The large central pine cone at the top of the bell tower is also made entirely of brick. It is believed to have been reconstructed in the upper half after being struck by lightning on 31 March 1242, which caused a partial collapse. Upon entering the bell tower through the door on the church-facing side, visitors enter a dark room with a cross-vaulted ceiling, possibly once used as a prison. Ascending the first staircase, supported by flying buttresses, one reaches a larger room on the first floor, where the tapering walls create a more expansive space. The tower’s walls are constructed from rubble, with a concrete layer between two facings. The external facing is made of whole bricks, while the interior alternates between tuff blocks and terracotta. As one ascends, the use of tuff blocks diminishes while terracotta increases, and in the lower bell chamber, older marbles have been reused.

Cloister of the Abbey of San Zeno

The cloister of the Abbey of San Zeno, dating back to the 10th century, underwent significant renovations between 1293 and 1313, giving it its present form. The cloister is surrounded by small arches, with pointed arches on two sides and round arches on the other two. These arches are supported by twin columns made of red Verona marble. On the northern side, there is a quadrangular aedicule, where the abbey’s ancient well once stood. The perimeter walls of the ambulatory are adorned with sarcophagi and tombstones, including the tomb of Giuseppe della Scala, dated to 1313 and enriched with a lunette fresco by an artist from the Giotto school.

The southern side features the tomb of the monks of the abbey, constructed in the 11th century by Abbot Alberico. While it is uncertain if this is the original tomb, it is made of red marble and is covered by a thick slab with a large cross in relief. Above the tomb, an inscription commemorates it. Next to it is a door leading to the upper church, adorned with a lunette fresco from the early 14th century depicting the Madonna with two angels.

On the eastern side of the cloister, there is a large fresco by the Veronese painter Jacopo Ligozzi, depicting the Last Judgment and an Allegory. A door on the same wall provides access to the Chapel of San Benedetto, which can be reached by descending a few steps. Above the chapel, a lunette fresco from the late 14th century depicts the Madonna with two holy bishops.

Shrine of Saint Benedict

Along the southern side of the cloister is the door to the Shrine of Saint Benedict, also known as the Sacellum (or Oratory) of San Benedetto. This small, square room is divided into three equal naves, each covered by nine cross vaults supported by four pillars, many of which are constructed from recycled materials dating back to various periods. Among the notable elements are a 6th-century Byzantine-style cushion and a Roman cippus embedded in one of the pillars. The walls are decorated with yellow, red, and green squares, a 14th-century style, and the north wall features a fragment of a faded fresco. Scholars have debated the date of the chapel’s construction, with many agreeing that it dates to the 12th century. Some believe the chapel may have been a restructuring of an earlier Roman-era structure from the 4th-5th century. The chapel may have originally served as a sacristy or chapter house. The name “San Benedetto” comes from a tombstone discovered in 1723, which commemorates a monk who financed the construction of this chapel for the church of Saint Benedict.

Internal Layout and Art of the Basilica of San Zeno

The Basilica of San Zeno is a magnificent example of Romanesque architecture, with an interior that is rich in historical and artistic value. Its design and decoration reflect the evolution of art over centuries, featuring layers of frescoes, altarpieces, and unique architectural elements.

Entry and Vertical Division of the Interior

Upon entering the Basilica of San Zeno, you ascend a few steps, symbolizing the spiritual detachment from worldly concerns, followed by a descent, which is an invitation to humility. This movement reflects a traditional symbolic approach in sacred architecture. The church follows a basilica layout, with the interior divided into three naves by two rows of imposing pillars and columns, ten on each side. The columns have a cruciform section and are surmounted by capitals adorned with zoomorphic motifs and Corinthian designs, many of which were repurposed from earlier Roman structures. The ceiling of the church is a wooden structure, designed in the shape of a ship’s hull with intricate decorations. Constructed between 1385 and 1389 during a Gothic renovation, the ceiling is considered an exceptional piece of art, rivaling the famous ceiling of the Church of San Fermo Maggiore. The nave is rhythmically divided by two large transverse arches, contributing to the overall visual harmony of the space.

Vertically, the church is divided into three distinct levels: the crypt, the plebeian hall, and the presbytery. The crypt is accessed via stairs at the end of the central nave, while the raised presbytery is accessed through stairs at the end of the smaller naves. The presbytery is separated from the main hall by a balustrade partition. Originally, the three naves of the church ended in three semicircular apses, as was typical in Romanesque architecture. However, only the southern apse remains in its original form, while the northern apse was incorporated into the abbey buildings, and the larger central apse was rebuilt in Gothic style in the 14th century.

Frescoes and Artistic Masterpieces

The walls of the Basilica are adorned with frescoes painted over a span of more than two centuries. Some of these frescoes have been damaged and overlaid by later works. The oldest frescoes can be found in the crypt, while the majority of the frescoes are attributed to two major groups of painters: the “first master” and the “second master” of San Zeno. The first master, working in the second quarter of the 14th century, is credited with introducing the Giotto school to Verona. The second master, active in the latter half of the 14th century, developed a more advanced painting style influenced by Lombard pictorial traditions. Their work is particularly noted for its richness and complexity, especially in the 24 votive paintings in San Zeno alone. Although most of the frescoes are attributed to these two groups, there are a few works by known artists, including Martino da Verona and Altichiero da Zevio. Some paintings bear inscriptions in German, left by monks from Germany who had long stayed at the abbey.

Right Aisle and Altarpieces

In the right aisle, near the entrance, a large octagonal marble baptismal font is located, traditionally attributed to the artist Brioloto, although this remains unproven. Hanging on the wall of the counter-façade, next to the entrance, is a 14th-century stationary cross, a remarkable work with a rich history. Its attribution has been debated, with some scholars attributing it to Guariento di Arpo, while others suggest influences from Lorenzo Veneziano. However, recent studies have concluded that the work was created by a young Venetian artist, influenced by the Giottoesque naturalism that was prominent at the time. The cross is adorned with gold leaf, and the figures include the Madonna, Saint John, the Eternal Father, and a kneeling Dominican monk, believed to be the patron of the work. The cross was used during the Lenten processions, where the bishop and faithful would visit various churches to venerate the preserved cross. Further along the right aisle, you will find a 16th-century altar with an altarpiece by Francesco Torbido, created around 1514. The altarpiece depicts the Madonna with Saints Anna, Zeno, Giacomo, Sebastiano, and Cristoforo, while the lunette above features a Resurrection scene that shows Torbido’s connection with his master, Liberale da Verona.

Romanesque and Gothic Altars

The right aisle also features a Romanesque altar, its columns made of red Verona marble and potentially coming from a 13th-century porch. These columns support a triangular tympanum, inside which a depiction of Saint Zeno is painted. The altar wall is adorned with frescoes, many of which are attributed to the second master of San Zeno, including scenes of the Madonna with Child, the Crucifixion, and the Deposition. The frescoes reveal the stylistic evolution from the 13th to the 15th centuries and reflect the different artistic movements that influenced the region.

Left Aisle and Historical Artifacts

In the left aisle, near the counter-façade, is a large red porphyry cup, measuring 2.27 meters in diameter. This cup originally came from the Roman baths of Verona and was once located outside the basilica in the southern churchyard. Legend has it that the devil transported the cup from Syria to Verona under the orders of Saint Zeno, and the marks visible on the cup are said to be those left by the devil’s nails. In 1703, a small building was constructed around the cup to protect it, and in 1819, it was relocated to its current position after the demolition of surrounding buildings. As you continue toward the altar, you will find a long section of bare wall, which once housed the main altar of the nearby Church of San Procolo. This Baroque altar, made of green, yellow, white, and lapis lazuli-colored marbles, was dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. It was relocated to San Zeno in the 18th century but was sold to the parish church of Luserna in 1929. Today, the altar has been replaced with a smaller altar dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

Sculpture and Frescoes in the Left Aisle

In the left aisle, you can also admire a 15th-century German-style sculpture of the Virgin Mary, who is depicted holding the body of her dead son on her knees. This sculpture is housed in an 18th-century altar dedicated to the Madonna. The altar also features two small golden statues of saints inserted in niches between four black marble columns. The soft stone statue of the Virgin Mary was once highly venerated in the Church of San Procolo. Further along the left aisle, you will find frescoes including a 14th-century depiction of Saint Christopher and a Last Supper scene. At the staircase leading to the presbytery, you can observe frescoes of the Martyrdom of Saint Stephen and a Last Judgment with Christ, Mary, Saint John the Evangelist, and Saint Zeno.

Pier-Partition and the Partition Wall

The pier-partition in the Basilica of San Zeno plays a critical role in dividing the plebeian area of the church from the presbytery. It is an architectural element that, while modern in some aspects, carries deep historical significance. The current partition, with its red marble balustrade and the placement of ancient statues, dates back to 1870 when the central staircase to the crypt was demolished, and lateral stairs were restored.

The original partition wall was much higher than the present one, a feature deduced from the frescoes above the arches in the crypt, which must have originally extended upwards. This partition has been compared to the iconostasis of the Byzantine tradition, with its symbolic division between the sacred space of the presbytery and the more accessible plebeian area. The iconographic elements of this partition recall the historical and liturgical importance of such divisions in ancient religious structures.

The Statues on the Pier

The statues placed on the pier today are traditionally attributed to the sculptor Brioloto. These figures, while weathered over time, still show traces of their original polychrome coloring. The arrangement of these statues, from left to right, includes the following apostles and figures: Bartholomew, Matthias, James the Less, the Evangelists Matthew and John, Peter, Christ, James the Greater, Thomas, Simon, Andrew, Philip, and Thaddeus. There is scholarly debate regarding the exact authorship of these statues. While some historians, such as Géza de Fràncovich, suggest that the statues were the work of two separate sculptors, the majority believe that they were all made by a single artist. Regardless of the number of sculptors, the statues exhibit a distinctive style, with elongated bodies, contracted limbs, and detailed, flowing garments. These stylistic choices are typical of early German Gothic art, a style that had a significant influence on Verona due to the city’s strong ties with the Germanic world during the 13th century, especially during the reign of Ezzelino III da Romano, who was allied with Emperor Frederick II of Swabia.

The only inscription still legible is found on the plinth of the statue of Christ, where the Romanesque lowercase phrase “vide tomas noli esse incredulus set fidelis” can be read. This phrase, translated as “See Thomas, do not be unbelieving but faithful,” is a reference to the biblical passage where Thomas doubted Christ’s resurrection. Some scholars, like Simeoni, suggest that this inscription may be linked to the fight against the Cathar heresy, which was prevalent around the banks of the Adige River at the time.

Presbytery of the Basilica of San Zeno

The presbytery of the Basilica of San Zeno is raised above the level of the plebeian area and is accessed by two staircases located in the side naves. Once inside, it is clear that the space is filled with a rich tapestry of artistic works from various periods. Many of the walls in the presbytery are adorned with frescoes that offer insight into the history of Verona, including references to significant events such as the flooding of the Adige in 1239, the sack of Verona by Gian Galeazzo Visconti in 1390, and the earthquake of 1695. The presbytery itself is structured around the central altar, flanked by side naves that culminate in two small lateral apses. At the back of the presbytery is the large main apse, which houses the choir. The left wall features a grand painting of the Crucifixion, attributed to Altichiero or his school. Adjacent to this, a statue of Saint Zeno, known as “Saint Zeno Laughing,” sits in the small apse on the left. This statue, created by an anonymous artist in the 12th century, is one of the most iconic representations of the patron saint of Verona.

On the right wall, frescoes from the 14th century depict scenes such as the Baptism of Jesus, the Resurrection of Lazarus, Saint George and the Dragon, and Saints Benigno and Caro carrying the body of Saint Zeno. The right apse of the presbytery is believed to be one of the oldest parts of the basilica, dating back to the 10th century. It is the only surviving original apse from the early structure. The altar of the Holy Sacrament was placed here in the 19th century.

High Altar and Sarcophagus of Saints

The high altar in the presbytery is an extraordinary feature, as it is built upon the sarcophagus of Saints Lupicino, Lucillo, and Crescenziano, three bishops of Verona. This sarcophagus, previously housed in the crypt, contains the relics of the saints, which were formally recognized in 1808. The sarcophagus is richly decorated in bas-relief, with scenes including the Crucifixion, the Four Evangelists, and images of Christ freeing souls from hell. The exact date of its creation remains uncertain, but some scholars suggest it was made around the early 10th century.

Andrea Mantegna’s Altarpiece

One of the most notable works in the presbytery is the altarpiece by Andrea Mantegna. This polyptych is a masterpiece of Italian Renaissance art and depicts the Madonna with Child surrounded by saints in the upper triptych, while the predella below shows scenes from the life of Jesus. The altarpiece was taken by the French during Napoleon’s invasion in 1797, and while the upper part of the polyptych was returned to Verona after several years, the predella remains in France. The current altarpiece seen in the basilica today is a copy by Paolino Caliari, a descendant of the famed painter Paolo Veronese.

Main Apse: Gothic Style and Martino da Verona

The current main apse, built between 1386 and 1389, is of Gothic design and features a polygonal shape. It is accessed through a large triumphal arch, frescoed with the Annunciation, a work by Martino da Verona, which was completed between 1391 and 1399. The frescoes in the apse also include a Crucifixion scene, created by a follower of Martino, which covers a previous depiction of Saint Zeno seated on a rich throne. The apse’s ceiling is decorated with a blue sky and eight-pointed stars, while the arches bear the coats of arms of Abbot Emilei, who commissioned the work. The cross vaults were designed by Giovanni and Niccolò da Ferrara, and under the apse basin, niches hold sculptures of Saints Peter, Paul, and Benedict.

Crypt: Architectural and Artistic Significance

The crypt, a crucial feature of the basilica, was constructed around the beginning of the 10th century and underwent several phases of restoration over the centuries. After the earthquake of 1117, it was rebuilt, and by the 13th century, it had been completed with the addition of a northern entrance. The crypt is divided into twelve naves and features 49 columns supporting 54 cross vaults, each with a unique capital, many of which display Byzantine influences. At the heart of the crypt lies the open sarcophagus of Saint Zeno, his body preserved in pontifical robes. The crypt also housed the sarcophagus of Saints Lupicino, Lucillo, and Crescenziano, which was later moved to the presbytery as the main altar.

Frescoes from various periods once adorned the crypt’s walls, although much of the decoration has deteriorated over time. Notable among the visible frescoes are fragments depicting the Madonna and Child, scenes of the Flight into Egypt, and various saints. The crypt’s entrance is adorned with marble friezes created by the sculptor Adamino da San Giorgio in 1225, depicting non-religious subjects such as fantastic beasts and hunting scenes. These friezes are particularly unique for their detailed depiction of everyday life, with figures engaged in activities like chasing wild animals or confronting monsters. The crypt’s entrance is also distinguished by an elegant iron gate, considered a fine piece of craftsmanship.

Feast Day

Feast Day : 12 April

The feast day of San Zeno Maggiore, the patron saint of Verona, is celebrated on April 12th each year. This date honors the life and legacy of Saint Zeno, who was the bishop of Verona during the 4th century and is venerated for his contributions to the Christian faith in the region.

Church Mass Timing

Monday : 8:00 AM.

Tuesday : 8:00 AM.

Wednesday : 8:00 AM.

Thursday : 8:00 AM.

Friday : 8:00 AM.

Saturday : 8:00 AM.

Sunday : 10:00 AM., 11:30 AM., 6:30 PM.

Church Opening Time:

Monday : 9:00 am – 6:30 pm.

Tuesday : 9:00 am – 6:30 pm.

Wednesday : 9:00 am – 6:30 pm.

Thursday : 9:00 am – 6:30 pm.

Friday : 9:00 am – 6:30 pm.

Saturday : 9:00 am – 6:30 pm.

Sunday : 1:00 pm – 6:30 pm.

Contact Info

Address :

Basilica of San Zeno Maggiore

Piazza San Zeno, 2, 37123 Verona VR, Italy.

Phone : +39 045 592813

Accommodations

Connectivities

Airway

Basilica of San Zeno Maggiore, Verona, Italy, to Valerio Catullo Airport (VRN), distance between 13 min (11.6 km) via Tronco T4-T9/SS12.

Railway

Basilica of San Zeno Maggiore, Verona, Italy, to Verona Porta Nuova Piazzale XXV Aprile, distance between 8 min (2.9 km) via Viale Colonnello Galliano.