Introduction

The Parish of Our Lady of Consolation and St. Stanislaus the Bishop in Szamotuły is one of the oldest Roman Catholic parishes in the region, with its roots stretching back to the 12th century. This long history is reflected in the beautiful Gothic collegiate church, which was constructed in the first half of the 15th century. The church stands proudly on Kapłańska Street, in the heart of Szamotuły, and has served as a spiritual center for the community for centuries. Over the years, it has witnessed countless religious and historical events, making it a significant landmark in the area.

The church in Szamotuły is the oldest monument in the town and one of the most significant examples of Gothic architecture in Greater Poland. It was built between 1423 and 1431 on the site of a previous church, thanks to the funding of Dobrogost and Wincenty Świdwa-Szamotulski. From 1423, the church housed a provost’s office and a College of eight mansionary priests. In 1542, Bishop Sebastian Branicki established a collegiate chapter, granting the church the title of collegiate church. Over the centuries, the church went through several expansions and renovations. In the 16th century, between 1513 and 1542, thanks to the efforts of Łukasz Górka, the chancel was narrowed and raised, new pillars and vaults were added, and a tower was built. The church underwent further expansions in the 17th and 19th centuries. During the Reformation, from 1569, the church was taken over by the Lutherans and later by the Czech Brethren in 1573, before returning to Catholic ownership in 1594. In 1666, a painting of Our Lady of Consolation was placed in the church. Despite suffering from floods and fires over the years, the church was renovated multiple times, including in 1772 when a new roof was added, funded by the sale of votive offerings. Major renovations took place between 1884 and 1890, including the construction of a bell tower, plastering of the interior, and the addition of a porch on the south side. The church endured significant losses during World War II. On October 6, 1941, German troops looted the church, stealing items like the bells, the painting of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary from the main altar, and a 16th-century tombstone. After the city’s liberation on January 27, 1945, the church was reopened to the faithful. The church was renovated again in 1952, and in 1970, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński crowned the painting of Our Lady of Consolation with papal crowns. In the same year, the church’s title was changed to the former collegiate church of Our Lady of Consolation and St. Stanislaus the Bishop and Martyr. In 2000, the Archbishop of Poznań restored the collegiate dignity, and a new Collegiate Chapter was established. In 2008, Cardinal Stanisław Dziwisz donated the relics of St. Stanislaus the Bishop to the church. In 2014, the church was granted the title of a minor basilica.

Architecture of Basilica of Our Lady of Consolation and St. Stanislaw, Szamotuły, Poland

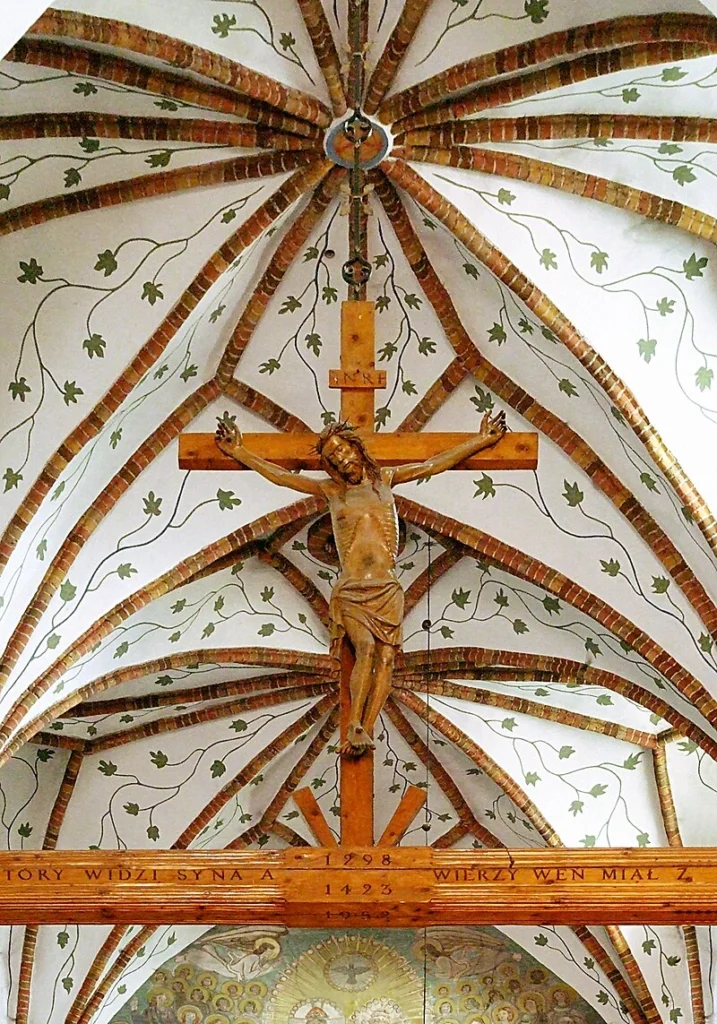

Fragment of the Star Vault – Szamotuły Basilica

This late Gothic brick church with three aisles was constructed following the Polish basilica layout. It has seven bays two in the choir area and five in the main nave and is shaped like a rectangle. The entire structure is approximately 47 meters long and 24 meters wide, and the central nave is approximately 20 meters high. Both the nave and the choir are divided into three parts, kind of like three parallel hallways running side by side. In the choir section, the north aisle is slightly shorter and narrower than the south aisle. This is due to the fact that there was once a sacristy on the eastern end of the northern aisle, which occupied some space. A large chancel arch separates the bays of the central nave from the choir on the interior, while smaller arches divide the sections of the side aisles. Bays in the side aisles are square, but those in the main nave and choir are rectangular. The arches between the aisles are pointed and supported by square pillars. The vaults overhead are star-shaped classic for this style. The side aisles have lean-to roofs, while the central nave has a gable roof. They’re all covered in tiles. A porch with its own solid, one-piece roof is on the south side. The church’s west front is divided by buttresses and has three colorful, profiled ceramic brick portals. Windows rise above those openings. At the top, there’s a stepped gable with blind (fake) windows. Even more complicated is the east end. A large buttress that runs through the center transforms into a hexagonal turret with a bell tower on top. The sacristy is also located here, and a small library is directly above it. The sacristy has a barrel vault ceiling. Many of the windows are bricked up quite high, particularly in the main nave, and they are splayedpointed arches that widen inward. Colorful paintings by Józef Filiger and Alojzy Gielniak, based on designs by Wacaw Taranczewski, decorate the interior brickwork in 1952. The Szamotuy Basilica’s overall shape and design are based on the “Silesian basilica” style, an older Gothic church model that can be found in parts of Germany and Poland.

Interior

The Triptych That Vanished

Right behind the altar, once upon a time, there used to be a stunning triptych from 1521. It showed the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, painted by someone whose name no one ever knew. It was a gift from Łukasz Górka, a nobleman, and it was the heart of the church’s main altar for centuries. The center panel had Mary being lifted into heaven, full of motion and light. On the side wings, you’d see St. Stanislaus and St. Martin, the church’s patron saints. Flip those wings over and there were even more saints eight of them: Cyril, Methodius, Catherine, Otilia, John the Evangelist, Luke, Barbara, and Dorothy. That triptych wasn’t just a painting it was a whole piece of history in itself. But in 1941, the Nazis stole it. Just took it. And for a long time, it was gone. Then, out of nowhere in the 1990s, a German journalist named Kerstin Holm found it in Ashgabat, in Turkmenistan. It was sitting in a museum there, hidden away. Turned out the Soviet army had gotten their hands on a bunch of stolen Nazi loot and sold a lot of it off, and that’s how this Polish church’s treasure ended up halfway across Asia. The triptych is still there. For years, Poland didn’t even have any real connection with Turkmenistan, so getting it back was impossible. But now, there’s hope. After decades, the church might one day get it home.

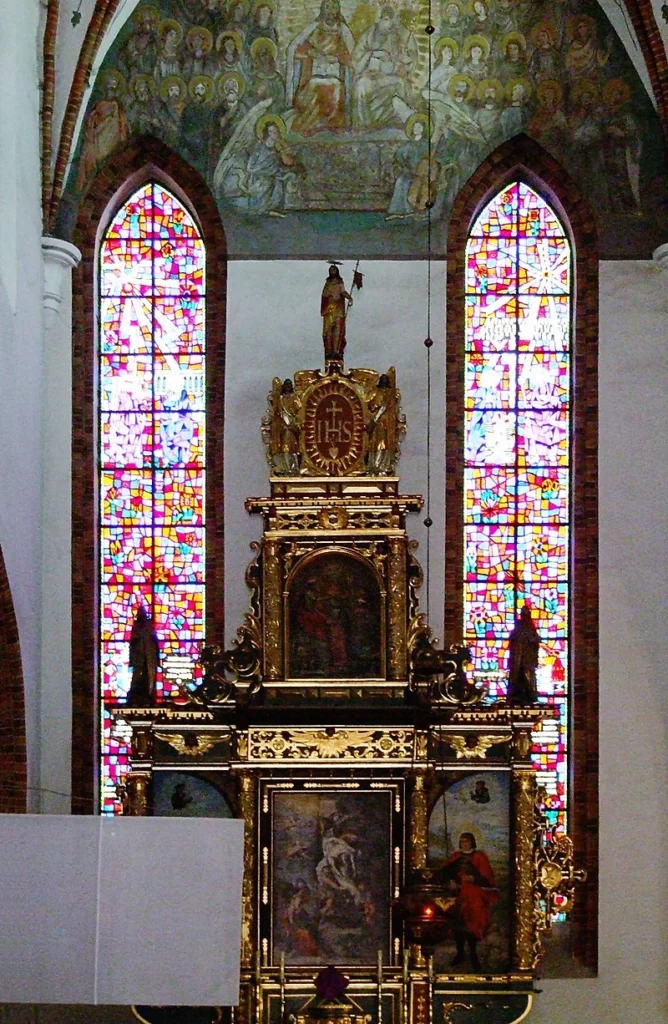

The Main Altar (After the Loss)

Since the triptych’s been gone, the church replaced it with a Late Renaissance altar, built around 1616. It’s big, tall, and full of detail. Carved wood everywhere patterns of vines, metal-like shapes, everything really intricate. The sculptor was probably Stanisław Kossiorowicz, a craftsman from Poznań. Up top, there’s a sculpture of Christ, resurrected, arms raised, with angels beside him. Just below that, you see St. Peter and St. Paul standing on each side, both holding their usual symbols. In the middle, where the triptych used to be, there’s now a copy of The Descent from the Cross by Luca Giordano. It’s not the same, but it tries to hold the space. The wings on either side show painted versions of St. Stanislaus and St. Martin, standing there as a quiet reminder of what was once there.

The Szamotuły Lady – A Local Icon

To the side, there’s another altar this one built in 1988 as a copy of an older Baroque altar from 1701. It’s colorful and decorated with rich carvings, almost like a piece of lace made out of wood. At the center of that altar is an icon known as the Szamotuły Lady. It’s actually a copy of the Russian icon Our Lady of Kazan, but it holds deep meaning for locals. She’s dressed in dark robes, holding the Christ child, who looks straight out at you. Surrounding her are painted figures of four saints: Adalbert, Stanislaus, Lawrence, and Stephen. And underneath, there’s a framed image of St. Stanislaus Kostka, surrounded by a kind of starburst his youthful face looking upward, lost in devotion.

Church Altars and Baptismal Font

One of the older side altars, dating back to the early 1600s, shows that classic Late Renaissance style with floral carvings, elegant columns, and small niches. Right in the center hangs a 19th-century painting of St. Barbara, holding a palm branch and standing calmly against a gentle landscape. Flanking her are statues of St. Sebastian and St. John the Baptist, each tucked into their own alcoves. Around the columns, you can find carvings of the twelve apostles, while two prophets sit quietly on the top cornice, watching over the whole scene. A bit newer is the Holy Cross Altar from 1886, built in a Neo-Gothic style. At its heart is a striking image of the crucified Christ, nailed high on the cross, his face a mix of sorrow and grace. On either side, statues of Mary and Mary Magdalene stand mourning, with wooden inscriptions above them that read “Behold your Son” and “Son, behold your Mother,” words meant to catch your attention and invite reflection. Nearby, in one of the chapels, there’s a Baroque altar dedicated to St. Joseph, showing him gently holding baby Jesus. The expressions on both their faces are soft and protective, while angels look down from above. Below this tender scene, carved into the altar’s base, is a depiction of the Flight into Egypt: Mary riding a donkey, Joseph leading the way, captured in a quiet, flowing motion. The baptismal font, one of the oldest pieces, dates back to the late 1500s. Made from sandstone and shaped like a six-sided chalice, it’s decorated with alabaster reliefs depicting key moments like the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Shepherds and Magi, the Circumcision, the Presentation at the Temple, and the Flight into Egypt. Each scene is small but finely detailed. The wooden lid on top was added much later, in 1804, carved to resemble a vase resting on a pedestal.

Tombstones and Memorials

One of the older side altars, dating back to the early 1600s, shows that classic Late Renaissance style with floral carvings, elegant columns, and small niches. Right in the center hangs a 19th-century painting of St. Barbara, holding a palm branch and standing calmly against a gentle landscape. Flanking her are statues of St. Sebastian and St. John the Baptist, each tucked into their own alcoves. Around the columns, you can find carvings of the twelve apostles, while two prophets sit quietly on the top cornice, watching over the whole scene. A bit newer is the Holy Cross Altar from 1886, built in a Neo-Gothic style. At its heart is a striking image of the crucified Christ, nailed high on the cross, his face a mix of sorrow and grace. On either side, statues of Mary and Mary Magdalene stand mourning, with wooden inscriptions above them that read “Behold your Son” and “Son, behold your Mother,” words meant to catch your attention and invite reflection. Nearby, in one of the chapels, there’s a Baroque altar dedicated to St. Joseph, showing him gently holding baby Jesus. The expressions on both their faces are soft and protective, while angels look down from above. Below this tender scene, carved into the altar’s base, is a depiction of the Flight into Egypt: Mary riding a donkey, Joseph leading the way, captured in a quiet, flowing motion. The baptismal font, one of the oldest pieces, dates back to the late 1500s. Made from sandstone and shaped like a six-sided chalice, it’s decorated with alabaster reliefs depicting key moments like the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Shepherds and Magi, the Circumcision, the Presentation at the Temple, and the Flight into Egypt. Each scene is small but finely detailed. The wooden lid on top was added much later, in 1804, carved to resemble a vase resting on a pedestal.

Old Crosses, Light, and Prayer in the Basilica

A large wooden crucifix that was carved in the year 1370 by an unknown artist hangs quietly just above the beam where the chancel opens into the main nave. Christ is depicted with his eyes closed, his body still and heavy, as if he were carrying not only the weight of the cross but also the prayers that have been whispered for centuries underneath it. The eternal lamp was a gift from King John Casimir in the early 1600s and hangs nearby in the chancel. Its brass is decorated with delicate angels and curving shapes that twist like smoke rising. The pulpit, which was added in 1893, has carved wooden panels and a small canopy in a Neo-Gothic style. It is where countless sermons have echoed throughout the church. Another Baroque crucifix, this one from the late 1600s, can be found in the porch area as you enter the church. It depicts a dark-wooded Christ with arms outstretched, not in pain but in quiet welcome to anyone who enters.

Coronation of the image and granting of the dignity of minor basilica

Thanks to the efforts of the parish priest of Szamotuły, Father Prelate Albin Jakubczak, Pope Paul VI issued a decree (December 3, 1969) authorizing the coronation of the image. The coronation ceremony took place on September 20, 1970. In the presence of 70,000 faithful and several hundred priests, Primate Stefan Cardinal Wyszyński, assisted by Archbishop Antoni Baraniak, Metropolitan of Poznań, and Bishop Edmund Nowicki, Ordinary of Gdańsk, solemnly coronated the image with papal crowns. 44 years later, on September 20, 2014, a solemn Mass was held, during which the papal decree granting the collegiate church the title of minor basilica was read . At the request of Archbishop Stanisław Gądecki – the Holy See – on June 22, 2014, the collegiate church received the title of minor basilica by decree of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. Thus, the Szamotuły church joined the group of four other minor basilicas in the Archdiocese of Poznań – the Archcathedral Basilica in Poznań, the Collegiate Basilica in Leszno , and the Basilica on Święta Góra near Gostyń.

Legends associated with the church

The Szamotuły collegiate church is wrapped in a web of intriguing legends that have been passed down through generations. One such tale suggests that on All Souls’ Day Eve, ghosts from the nearby cemetery emerge and use their shins to carve holes in the church’s walls. According to the legend, these holes are signs that, when fully formed, the end of the world will come. In truth, the marks on the church walls were made by the faithful, who in ancient times believed that the powdered brick from the walls held healing powers. Another story ties the church to Halszka of Ostróg, who, according to local lore, used to pray in a niche within the church. She would enter the church through a secret tunnel that connected to the tower where her husband, Łukasz III Górka, had imprisoned her. This connection between love, imprisonment, and prayer adds a layer of mystery to the church’s history. Then there’s the story of an old elm tree that once stood near the church. It’s said that King John III Sobieski feasted under its branches. The tree became a bit of a local legend itself. Despite being short, it was thick and obstructed processions and funeral rites. Attempts to cut it down failed spectacularly: several lumberjacks’ axes could not harm the tree. Then a saw was brought in, but it broke, and blood poured from the bark. The parish priest at the time ordered the work to cease, and the tree was left to grow. Years later, a new priest tried to cut it down, but the same strange events occurred. Eventually, the tree grew tall and strong, its last bleeding event said to have taken place after the Third Partition of Poland. The “Marysieńka elm,” which stood near the church until 1980, is also part of local lore. Legend has it that King John III Sobieski himself planted it, further tying the church’s surroundings to the king’s legacy. Lastly, there’s a more solemn legend related to the icon of Our Lady of Consolation. It’s believed by some that this icon originally came from the camp altar of King John III Sobieski himself, adding a royal connection to the sacred relic kept in the Szamotuły church.

Surroundings

The Szamotuły collegiate church is surrounded by natural beauty, with several old chestnut trees growing nearby, some with a circumference of up to 250 centimeters. Not far from the rectory, a common yew tree stands tall with a circumference of 160 centimeters. Until 1980, three magnificent elms stood near the church. The oldest, “Marysieńki Elm,” was a remarkable 500 years old, with a circumference of 760 centimeters, making it the thickest elm in Greater Poland. “Sobieski Elm” was approximately 450 years old with a circumference of about 600 cm, while the “Elm of the Year 1683” had a circumference of 250 cm and was about 250 years old. These elms were officially declared natural monuments by the Provincial National Council in Poznań in 1956, becoming symbols of the church’s rich heritage.The church itself is surrounded by a red brick wall, with gates to the east and west. The western gate provides access to the church, while the eastern gate, built at the end of the 19th century, features a crucifix from the third quarter of the 18th century. This crucifix originally came from the Church of the Holy Cross in Szamotuły, adding a historic touch to the entrance. Standing at the eastern wall is a red brick bell tower, designed by Stefan Cybichowski and consecrated in 1930 by Poznań Bishop Walenty Dymek. The tower once housed bells, one of which played the chime “Witaj śliczna i dzienna Szamotuł Pani” (“Hail, lovely and hereditary Szamotuł Lady”) composed by Feliks Nowowiejski. This bell chime first rang on December 24, 1930. Unfortunately, during World War II, in 1941, the Nazis stole the bells and melted them down to make weapons, robbing the church of its sound. In the square next to the church, a monument was erected in 2003 to mark the 25th anniversary of John Paul II’s pontificate. The monument features a bas-relief of the pope in an embrace with Primate Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński. Further along, a wooden cross and a boulder with a plaque bear the words: “Where are their graves, Poland! Where they are not, you know best and God knows in heaven!” This quote, from Artur Oppman’s “Prayer for the Dead,” was spoken by John Paul II during a homily in Warsaw on June 2, 1979. In the southwest corner of the church wall, a stone grotto of Our Lady with Child was built in 1948, thanks to the efforts of Father Prelate Franciszek Forecki. The grotto was a heartfelt gift from the people of Szamotuły to honor the church’s survival through the hardships of World War II.

Feast Day

Feast Day : 11 April

The feast day for the Basilica of Our Lady of Consolation and St. Stanislaus the Bishop in Szamotuły is April 11th, which is the feast day of Saint Stanislaus, Bishop and Martyr. He is a significant figure in Polish history and is also the patron saint of the church.

Church Mass Timing

Monday to Saturday : 07:00 AM, 08:00 AM, 06:30 PM

Sunday : 07:00 AM, 09:00 AM, 10:30 AM, 12:00 PM, 06:30 PM

Church Opening Time:

Monday to Sunday : 7:00 am, 7:00 pm.

Contact Info

Address : Collegiate Basilica of Our Lady of Consolation and St. Stanislaus the Bishop in Szamotuły

Kapłańska 12, 64-500 Szamotuły, Poland.

Phone : +48 61 292 02 82

Accommodations

Connectivities

Airway

Basilica of Our Lady of Consolation and St. Stanislaw, Szamotuły, Poland to Poznań-Ławica Airport, distance between 41 min (32.3 km) via DW184.

Railway

Basilica of Our Lady of Consolation and St. Stanislaw, Szamotuły, Poland, to Szamotuły Railway Station, distance between 4 min (1.3 km) via Dworcowa.