Introduction

Basilica di Santa Maria in Ara Coeli also known as the Basilica of Saint Mary of the Altar in Heaven (Latin: Basilica Sanctae Mariae de Ara Cœli in Capitolio, Italian: Basilica di Santa Maria in Ara Cœli al Campidoglio) is a titular basilica in Rome, located on the highest summit of the Campidoglio. It is still the designated church of the city council of Rome, which uses the ancient title of Senatus Populusque Romanus. The present cardinal priest of the Titulus Sanctae Mariae de Aracoeli is Salvatore De Giorgi.

The shrine is known for housing relics belonging to Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine, various minor relics from the Holy Sepulchre, both the pontifically crowned images of Nostra Signora di Mano di Oro di Aracoeli (1636) on the high altar and the Santo Bambino of Aracoeli (1897).

History of Basilica di Santa Maria in Ara Coeli

Originally the church was named Sancta Maria in Capitolio, since it was sited on the Capitoline Hill (Campidoglio, in Italian) of Ancient Rome; by the 14th century it had been renamed. A medieval legend included in the mid-12th-century guide to Rome, Mirabilia Urbis Romae, claimed that the church was built over an Augustan Ara primogeniti Dei, in the place where the Tiburtine Sibyl prophesied to Augustus the coming of the Christ. “For this reason the figures of Augustus and of the Tiburtine sibyl are painted on either side of the arch above the high altar”. A later legend substituted an apparition of the Virgin Mary.

In The History of Money, anthropologist Jack Weatherford goes into some detail about the church’s previous incarnation as the temple of Juno Moneta on the Arx after whom Money is named.

According to Roman historians, in the fourth century B.C., the irritated honking of the sacred geese around Juno’s temple on Capitoline Hill warned the people of an impending night attack by the Gauls, who were secretly scaling the walls of the citadel. From this event, the goddess acquired [the] surname-Juno Moneta, from Latin monere (to warn). As patroness of the state, Juno Moneta presided over various activities of the state, including the primary activity of issuing money.

From Moneta came the modem English words mint and money and, ultimately, from the Latin word meaning warning. Today, the site of the Temple of Juno Moneta, the source of the great stream of Roman currency, has given way to the ancient, brick church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli. Centuries ago, church architects incorporated the ruins of the ancient temple into the new building. The church is also thought to have replaced the auguraculum, the seat of the augurs.

The foundation of the church was laid on the site of a Byzantine abbey mentioned in 574. Many buildings were built around the first church; in the upper part they gave rise to a cloister, while on the slopes of the hill a little quarter and a market grew up. Remains of these buildings such as the little church of San Biagio de Mercato and the underlying “Insula Romana”) were discovered in the 1930s.

At first the church followed the Greek rite, a sign of the power of the Byzantine exarch. Taken over by the papacy by the 9th century, the church was given first to the Benedictines, then, by papal bull to the Franciscans in 1249–1250; under the Franciscans it received its Romanesque-Gothic aspect. The arches that divide the nave from the aisles are supported on columns, no two precisely alike, scavenged from Roman ruins.

During the Middle Ages, this church became the centre of the religious and civil life of the city. in particular during the republican experience of the 14th century, when self-proclaimed Tribune and reviver of the Roman Republic Cola di Rienzo inaugurated the monumental stairway of 124 steps in front of the church, designed in 1348 by Simone Andreozzi, on the occasion of the Black Death. Condemned criminals were executed at the foot of the steps; there Cola di Rienzo met his death, near the spot where his statue commemorates him.

In 1571, Santa Maria in Aracoeli hosted the celebrations honoring Marcantonio Colonna after the victorious Battle of Lepanto over the Turkish fleet. Marking this occasion, the compartmented ceiling was gilded and painted (finished 1575), to thank the Blessed Virgin for the victory. In 1797, with the Roman Republic, the basilica was deconsecrated and turned into a stable.

Sanctuary

This part of the church is not mediaeval. Originally there was an apse with a conch, and the latter had a mosaic by Pietro Cavallini featuring the Ara Coeli legend and the emperor having his vision. However the friars wanted the conventual choir behind the altar instead of in the transept and nave, so the apse was demolished and replaced with the present combined sanctuary and choir on a rectangular plan in 1565. The work impinged on the old well-cloister of the friary, just to the east.

The present high altar dates from 1723. The late Baroque aedicule is unusual in not having any pilasters or columns, but has a pair of gilded stucco angels on the truncated triangular pediment venerating the Franciscan version of the monogram of Jesus within a gilded glory.

Enshrined in the aedicule is a Byzantine-style icon of the Madonna and Child, known as the Madonna d’Aracoeli. It is painted on beech wood, and is nowadays tentatively dated to the 10th century. Some scholars formerly claimed that it might be older, perhaps as old as the 6th century; they connected it with the Greek monks who built the first church here. It used to be part of a larger artwork, an iconostasis or triptych, since Our Lady is gesturing to a missing representation of Christ. Interestingly, the style is very similar to the venerated ancient icon at Sant’Alessio.

According to the fictional tradition just mentioned, the icon was venerated and carried through the streets of Rome by St Gregory the Great during an epidemic. It certainly was so carried during the Black Death of 1348, and the short duration of that outbreak was ascribed to the intercession of Our Lady of Aracoeli. The people of the city put up the money for the access stairs in gratitude.

The icon was crowned in 1636, but the crown was stolen by French troops in 1797. A new crown was added in 1938, and in 1949 the Roman people were consecrated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary before this icon. The crown was removed in a recent restoration, as adding jewelled crowns to the images on ancient icons has now fallen entirely out of favour.

A work by Raphael, the Madonna of Foligno, was hung here instead of the icon from 1512 to 1565 before being taken to a convent in Foligno. it is now in the Vatican museums, in the Pinacoteca. The tomb of Sigismondo Conti, who commissioned the painting, is in the pavement on the right side.

Below the icon is a Cosmatesque panel, and flanking it are two statues of heroes bearing the shield of the city.

The altar “pro populo” in front of the high altar, for Masses said facing the congregation, is better than the usual ones in Roman churches. Here, the mensa is supported by a pair of gilded angels which echo those on the aedicule behind.

Exterior

The church is basilical in plan. It has a nave of twelve bays with side aisles, followed by a transept and then by the sanctuary with choir. The three pitched and tiled roofs of central nave, transept and sanctuary form a Latin cross.

The side chapels were added ad-hoc, and have individual roofs. There are nine off the left hand aisle, all about the same size and not aligning with the bays of the nave. The right hand aisle has eight, with a side entrance vestibule occupying the space for the ninth, and three of these chapels have apses -the fourth, fifth and sixth. Also, their width varies and the fourth is the biggest.

A further pair of external chapels flanks the sanctuary. Oddly, the right hand one of this pair (now the Blessed Sacrament Chapel) has yet another chapel opening off it to the right which it is easy for visitors to overlook.

The shop, sacristy and the Bambino Chapel are off the left hand end of the transept. There is a chamber over the last aisle chapel at this end, and in between this and the transept roof is the campanile of 1537. This has the form of two very tall arches in brick, looking like a fragment of a railway viaduct, with a triangular pediment on top containing a little round-headed aperture. The bells are dated 1566, 1595, 1615 and 1719.

The original church fabric is of scavenged ancient bricks. From the Piazza del Campidoglio, you can see that the rectangular windows of the central nave used to be Gothic with two lights each; tracery from the tops of these windows has been left embedded in the brickwork.

If you go round to the left hand end of the transept, next to the Vittoriano, you can see some tufa masonry low down in the external wall. This looks as if it belonged to the previous Benedictine church.

Staircase

The impressive staircase leading up to the church, which comprises124 marble steps (the two bottom ones shorter than the rest), was designed by Lorenzo di Simone di Andreozzo in 1348, and donated to Our Lady by the people of the city as a thanksgiving for the deliverance of the city from the plague. The marble was looted from ancient buildings, and there are traces of carving to be found on some of the slabs.

This staircase has always belonged to the city of Rome, and was a traditional site for political debates. Also, destitute pilgrims and indigents used to sleep here. A rather satirical modern myth has grown up, that if you climb the stairs on your knees you will win the Italian national lottery.

The little garden on the right has been there since Michelangelo laid out the Piazza del Campodoglio in the late 16th century. However, to the right there used to be a series of domestic buildings starting with the church of St Rita where the ruins of the ancient insula now are. Their loss was a pity; one of them had an ancient Roman sarcophagus built into it, and also (rarer) fragments of 11th century marble plutei or sanctuary screens in a Byzantine style. These seem to have come from the Benedictine church.

Do take care with these stairs if you are infirm, or if the weather is bad. If you fall, you are liable not to stop until you reach the bottom. If in doubt, use the side entrance of the church off the Piazza del Campodoglio.

Façade

The fabric of the frontage is largely original 13th century brickwork, and you can tell that the friars scavenged the ancient bricks from different buildings. The façade was never completed according to the original plans, and it was not intended to leave the brickwork exposed. Efforts were made to add a façade right up to the mid-19th century.

What we have is basically a brick cliff, displaying shallow putlog holes for the builders’ scaffolding poles. It has three entrances, with two round windows having marble transennae above the side ones. The portions of the façade above these are false, being screen walls above the actual side aisle roofs. In the centre is a rectangular niche containing an unusual heart-shaped window.

At the top is a cavetto cornice; that is, a horizontal wall which curves outwards and which contains a little round-headed window lighting the void above the nave ceiling. The reason for the curve is that there used to be a mosaic here, and the curve meant that it was not fore-shortened when viewed from the top of the stairs. Only a few small fragments remain, but Cellini in the 16th century saw it and thought that it had been executed by Jacopo Torriti. The subject was the Dream of Pope Innocent III; the story is that the dream reassured the pope about the basic orthodoxy of the nascent Franciscan movement at a time at the end of the 12th century when it was in danger of being condemned as heretical.

The three entrances are not in their original state. The main entrance has a floating porch in the form of a semicircular arch, and in the tympanum of this are traces of a fresco executed in 1465. The side doors have Gothic tympani containing two Evangelists in 16th century shallow marble relief, St Matthew to the right and St John to the left.

The aperture in the cornice used to have a clock in it, installed originally in 1412 (very early for a clock) as the city’s main timepiece. It had two attendants, the Moderatores Horologi, to make sure it kept the right time. The problem was, until the 19th century Rome kept to the ancient form of telling time which was to divide daylight and night-time into twelve “hours” each. Since obviously the length of the day changed through the year, the clock had to be reset daily. Perhaps partly because of this, it caused a lot of trouble by going wrong and breaking down. If you look carefully, you can see the round scar left by it. The clock was moved to the centre of the façade in 1728, and removed altogether in 1806.

The central window used to have a Baroque frame, and between it and the cornice was a large fresco. Both of these embellishments were removed senselessly in the 20th century (the fresco was badly decayed when it was destroyed).

To the left of the main entrance is a plaque recording the provision of the staircase. It reads: Magister Laurentius Simeoni Andretii, Andrea Karoli fabricator de Roma de regione Columpne fundavit, prosecutus est et consumavit ut principalis magister hoc opus scalarum inceptum anno domini ann CCCXL VIII die XXV Octobris. Some mediaeval tomb-slabs were re-used in the paving outside the main entrance, but these are too worn to decipher or even properly to date.

Side Entrance

The side entrance from the Piazza del Campodoglio, on the right hand side of the church, is behind the Palazzo Nuovo and is accessed via a short staircase. It is in the same style as the main entrance, but here the tympanum under the arched porch has a mosaic of The Madonna and Two Angels by the school of Pietro Cavallini or by Jacopo Torriti. This was transferred from the original side entrance in 1564 to make way for the present Chapel of St Matthew. It is easy for visitors to miss it.

Over this entrance are the remains of the original mediaeval Romaneque campanile. There is a brick wall of two storeys each with an arcade of three molded arches, the first arcade being blank but the second one piercing through the wall.

Friary

To get to this entrance from the piazza, you have to go up some stairs and then turn left around the back of the Palazzo Nuovo. At the top of the stairs is a loggia with a pitched and hipped roof, displaying an arcade of three arches separated by Doric pilasters. This was the entrance gateway to the friary, and is the only surviving part of it. The staircase has two flights, and on the intervening landing is a granite Corinthian column with a stone ball on top of it. The latter used to have a cross finial which has gone missing (it has recently been replaced).

The Franciscan friary was a very serious loss, some of the fabric being over six hundred years old when demolished (most was early 16th century). It was arranged round three cloisters or courtyards. Once through the gate, you found yourself in a tiny triangular courtyard with the actual entrance door in the far corner. Through that was the well cloister, fitted against the choir of the church and having two-storey arcades on the other three sides. These had ancient arcade columns with ancient capitals in the Ionic style in the first storey and in a foliated mediaeval style in the second one. The wellhead was in carved stone, and the well was very deep.

The main cloister was to the north of this, perched right on the crag and slightly out of square to fit. It was arcaded on all four sides, the arcade passages having Gothic cross-vaults. Finally, along the north side of the church was a long, narrow garden court with a range on its own north side which looked down to the Piazza Venezia and features in old depictions of the city.

Interior

The body of the church is made up of a central nave and two side aisles, The twenty-two antique columns in the arcades were salvaged from a variety of ancient buildings and are a very mixed lot in various stones and styles. The capitals also vary, some being Doric, some Ionic and others Corinthian or Composite and, because the columns vary in length, some have bases, some have their bases on plinths and others have no bases at all.

The third column on the left is inscribed with the letters E CVBICVLO AVGVSTORVM and is said to have come from one of the bedrooms (cubicula) of the imperial palace on the Palatine. A more likely source is a building on the Capitoline misidentified as the palace of the emperor who saw the vision of the Ara Coeli . Nobody knows why this column should have a hole through it; the suggestion that it was used for astronomical observations is a guess.

The last column on the right has another graffito, saying PROBI which means “useful ones”. Was this approval for use in building the church? The floor is a delightful mixture of Cosmatesque work and a large number of tomb slabs. When slabs were inserted, the Cosmatesque stone pieces were sometimes relaid haphazardly but other surviving areas are very intricately designed. Most of the carved floor slabs are very worn, but are still worth examining.

Above the arcades run a pair of entablatures, and on the projecting cornices of these are iron railings making two very narrow walkways. These meet below the window in the counterfaçade.

Above each column, placed over the entablature, is an elliptical tondo containing a fresco of a Franciscan saint. These total twenty-two, and were painted by one of the friars called Umile da Foligno. Unfortunately, he did not label them. The sleepy nun about to drop out of her tondo, with her little dog trying to get onto her lap, is St Margaret of Cortona. The dog features twice in this church -see her chapel.

Between the central nave windows are large rectangular fresco panels depicting scenes from the lives of Our Lady, King David, and the prophet Isaiah. These which were executed by Umile as well as by Giovanni Odazzi and Giuseppe Passeri. The style of these panels is lively and ebullient, and they are worth a look.

The coffered and gilded wooden ceiling, one of the glories of the church, commemorates the Battle of Lepanto (1571). One of the admirals there was Marcantonio Colonna, who was in charge of the papal contingent and who was given a triumphal procession ending in this church. In the centre coffer is a wooden relief carving of the Virgin and Child, with a pair of city shields (SPQR) either side on the major axis. The side coffers show battle trophies, including beaks of galleys (this was a naval battle between the combined Christian forces and the Ottoman Empire). The carving is very intricate, and tricked out in blue, red, green and gold. The transept has a matching ceiling.

The aisles have undecorated barrel-vaults with pointed arches, which do not meet in the middle to create cross-vaults. The finely carved wooden pulpit on the left hand side is thought to have been designed by Bernini.

Transept

The transept is structurally distinct from the nave, and is entered through a triumphal arch up three stairs. The ceiling here is as good as that of the nave, but often overlooked. The central coffer contains a wooden relief that looks like St Francis in glory with putti.

On the inner sides of the piers of the triumphal arch are two Cosmatesque ambones or pulpits dating to around 1200 and hence belonging to the previous Benedictine church. One theory is that they are constructed with parts from a single schola cantorum that used to be in front of the high altar, but a recent revisionist theory suggests that they were made at different times.

The one on the right is older, and is signed by Lorenzo di Cosma and his son Giacomo. The preservation of the ambones was fortunate, but they have certainly been altered and a panel from the right hand one is now in the Capitoline Museum. This shows a 4th century relief featuring scenes from the legend of Achilles. The workmanship of these items is amazing, and bears close examination.

Over the right hand ambo is a small fresco by Giovanni de’ Vecchi showing the icon of Our Lady of Aracoeli being taken in procession through the city by Pope Gregory the Great during an epidemic. Over the left hand one is a memorial to Catherine, Queen of Bosnia, 1478.

The Cosmatesque floor has two enormous porphyry roundels, sawn from a very high-status ancient column. Alarmingly, the left hand one has had a Baroque tomb slab cut into it and both are badly cracked. This floor was re-laid when the choir was built, and the schola here removed.

Choir

The choir is behind the high altar, and is inaccessible to visitors. Nowadays it is the home of the church organ, which hulks behind the altar in a rather unfortunate way. An organ was first installed here in 1848, but the present instrument dates from 1926. The choir screen walls, either side of the main altar, have a pair of entrance doorways. Over these are busts of SS Peter and Paul, and large statues of SS Bernardine and Anthony.

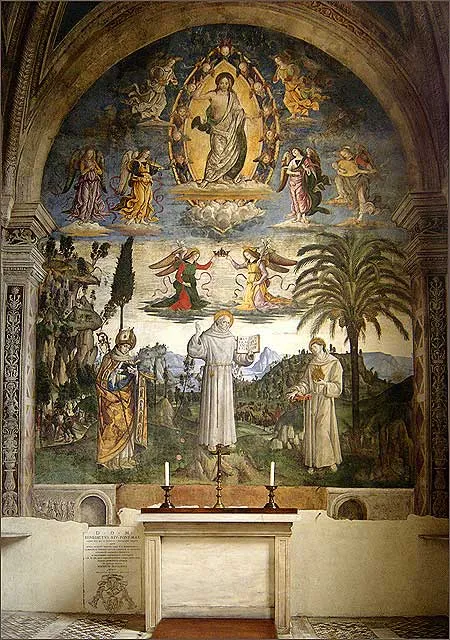

The frescoed barrel vault features Our Lady venerated by angels (some of which are playing musical instruments) by Nicolò Martinelli, Il Trometta. In the side panels are the emperor Augustus and the Tiburtine Sybil, an allusion to the apse mosaic or fresco by Cavallini which was destroyed to build the choir. On the left hand wall is a monument to Giovanni Battista Savelli by Andrea Bregno, 1498.

Paintings in here are of St Francis by Odoardo Vicinelli, and Bl John del Prado by Francesco Bertasi. The latter was a Spanish Franciscan martyred at Marrakesh in Morocco in 1631 while ministering to Christian slaves. The chapels are described in anticlockwise order, starting from the right of the main entrance.

Feast Day – 29th March

Annual Feast Day of Basilica di Santa Maria in Ara Coeli, Rome, Italy is celebrated on 29th March.

Mass Time

Weekdays

Sundays

Church Visiting Time

Contact Info

Scala dell’Arce Capitolina,

12, 00186, Rome, RM, Italy

Phone No.

Tel : +39 06 6976 3839

Accommodations

How to reach the Basilica

Giovan Battista Pastine International Airport also known as Rome–Ciampino International Airport “G. B. Pastine” in Rome, Italy is the nearby Airport to the Basilica.

Venezia Tram Stop in Rome, Italy is the nearby Tram Station to the Basilica.