Introduction

St. Mary’s Church (Polish: Bazylika Mariacka, German: St. Marienkirche) is a co-cathedral and Roman Catholic church in the center of Gdask, Poland. One of the largest brick churches in the world and one of the city’s most significant landmarks, the Crown of Gdask (Polish: Korona Gdaska) was completed in 1502 in the Brick Gothic architectural style. Together with Oliwa Cathedral, it serves the Archdiocese of Gdańsk. While the actual church’s construction began in 1379, the groundbreaking ceremony took place in 1343. St. Mary’s is an aisled hall church with a transept; its exterior was largely influenced by other churches and temples built across cities or townships in proximity to the Baltic Sea that were part of the Hanseatic League. Between 1536 and 1572, St. Mary’s Church was used for Catholic and Lutheran services simultaneously. Additionally, a domed side chapel in the Baroque fashion was erected for the Kings of Poland and Catholic worship in the late 17th century. It is one of the three largest brick churches ever built, along with San Petronio in Bologna and the Frauenkirche in Munich, with a seating capacity of more than 25,000 and a volume of approximately 155,000 cubic meters (5,500,000 cubic feet). It was also the second largest Lutheran church in the world from the 16th century until 1945. The structure is 105.5 metres (346 ft 2 in) long, and the nave is 41 metres (134 ft 6 in) wide; the total width of the church is 66 metres (216 ft 6 in). The internal height is estimated at 29 metres (95 ft 2 in) at maximum point.

The oldest history

The origins of the Gdańsk Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary remain unclear. Despite the fact that archaeological excavations beneath the current site have yielded no tangible evidence, it is believed that the church was built in 1243. It is believed that a wooden church, built by Duke Swietopelk II the Great , previously stood on the site of the current St. Mary’s Basilica, which was mentioned in 1271 along with other churches in Gdask (St. Nicholas and St. Catherine )

Construction of a Gothic church

Under a privilege granted to the Main Town in 1342 by the Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights , Ludolf Kónig , the decision was made to build a parish church. The current church’s construction began in 1343. A Latin inscription on a plaque at the entrance to the sacristy indicates that the first stone was laid on March 23: “Anno Domini MCCCXLIII… proxima feria sexta post Letare positus est primus lapis muri ecclesie beate virginis Marie cuius dedicatio celebrabitur dominica proxima post festum nativitatis Marie” On both of the church’s sides, the eastern and western, construction began simultaneously. Some fragments of the former brick structure have survived within the walls of the present hall. On the western side, a two-story, low bell tower with massive buttresses was built. Two chapels adjoined the tower, extending the side naves. The conditions imposed by the Teutonic Knights, who instructed it not to exceed the height of the previous castle tower, dictated the tower’s height. The former church most likely had the form of a three-aisle basilica, with a six-bay nave, the central nave of which reached approximately 27 meters. The original presbytery’s appearance is unknown due to changes during subsequent construction phases. It is believed to have had a three-aisle basilica form, also resembling a basilica, with a simple closure. The Gdask residents were in charge of its construction from the beginning. However, in contrast to other parish churches in larger Hanseatic cities, the rights of Gdask citizens were restricted by the Teutonic Order, so the church’s design did not align with the goals of the Main City’s residents. Construction was completed between 1360 and 1361. The fact is that the next generation constructed the church’s chancel, introducing a radical change to the original spatial concept, regardless of the hypotheses regarding the shape of the church’s chancel built by the previous generation. A three-nave transept with a hall layout was built before the chancel, and the chancel was expanded in a similar manner. Construction of the eastern part, conceived in this way, began in the 1370s, and in the years 1379–1400 the outer walls of the hall transept and chancel were erected. Master mason Henryk Ungeradin, who is also known for building the Main Town Hall, oversaw the project. In 1424–1447, the transept and chancel were expanded, roofed, and their gables finished. As a result of these changes, a disproportion in the external appearance of the church between the eastern and western parts was created. In the last quarter of the 14th century, the Gdask City Council assumed patronage over the church’s construction, directing its organization, management, and financing. During the Thirteen Years’ War, between 1454 and 1466, the tower was raised, symbolically marking the Gdańsk victory over the Teutonic Order. The turrets at the nave intersection and those flanking the transept and chancel were also raised. The remaining basilica-like portion of the nave was converted into halls and the side aisles were expanded between 1484 and 1498. Beginning in 1485, the architect Hans Brandt contributed to the construction, including the nave. In 1498–1502, the church was covered with star, net, and crystal vaults designed by Henryk Hetzel. The vault’s final keystone was inserted on February 28, 1502. The interior of the church is illuminated by 37 massive windows of varying sizes, only two of which are brand-new stained glass. 29 chapels were arranged in the large spaces that were created between them by installing buttresses inside. In 1518, on the initiative of the then parish priest, Maurycy Ferber , a rectory in the early Renaissance style was built next to the church.

Lutheran period

The Reformation, which began in 1517, reached Gdask about a dozen or so years after the construction was finished. The Gdask parish church hosted the first Protestant service in 1529, but Catholics used the main altar until 1572 and did not retake control of the church until 1945. Although for centuries the church served the Lutheran community, until the second half of the 17th century, the church’s pastors were Catholic clergy appointed by the Polish king. The Royal Chapel was built in the 17th century next to St. Mary’s Church to conduct services for Gdańsk’s Catholics. The original medieval decor was largely preserved in accordance with Martin Luther’s teachings, but the polychrome walls were whitewashed. The construction of a new organ, baptismal font, and pulpit accentuated the new liturgical space within the church. The Gdask patricians were the patrons of the temple, and they gave it many works of art, most of which showed the power of the Gdask people through their rich ideological content. Johann Sebastian Bach wrote an autobiographical letter to Georg Erdmann, a young friend of his who lived in Gdask, on October 28, 1730. In it, Bach unsuccessfully sought, among other things, “a highly favorable recommendation” for the Kapellmeister position at Saint Mary’s Church (number 8) Despite experiencing significant damage during the previous war, the church has undergone a series of renovations since the 19th century that have significantly strengthened its structure including the western tower. The so-called Kriegsdenkmal, which also commemorates the Prussian victory during their war with France in 1870–1871, is one of several monuments that have been placed in the interior. Other monuments include the Martin Luther monument, which was erected on November 10, 1883, and was taken down in 1946.

The Free City of Danzig and World War II

The famous buildings of the city were depicted on the Gdask guilder notes rather than portraits of notable individuals. The basilica was included in the 25-guilder denomination. After the September Campaign, the Germans issued stamps with the slogan ” Gdańsk is German,” and these also depicted the city’s famous buildings.

War damage and reconstruction

During the battles for Gdańsk in March 1945, as a result of artillery fire, the wooden roof structures burned down, 40% of the vaults collapsed, and some bells melted, including the largest one, Gratia Dei , weighing 5,300 kg and cast in 1453. Some of the equipment was destroyed or scattered; the exhibits are located, among others, in the National Museum in Warsaw. After clearing the interior of rubble and securing the pillars and remaining vaults in 1946, Professor Stanislaw Obmiski led the reconstruction effort, which was then led by architect Marian Kossakowski until 1950. Around 200,000 roof tiles were installed on the roof during this time. The church was consecrated and given to the faithful on November 17, 1955. However, work on the turret dome and tower roof reconstruction continued. Gothic polychrome fragments were discovered as the salvaged furnishings were gradually returned. A layer of white limestone was applied to the walls and vaults between the years 1982 and 1983.

Recent events

The National Council’s decision on January 29, 1946, handed the church over to the Roman Catholic Church. On November 20th, 1965, ten years after the church was consecrated, Pope Paul VI elevated St. Mary’s Church to the dignity of a minor basilica, and on 2 February 1987 it became the co-cathedral of the diocese, and from 1992 of the Gdańsk Metropolitanate. Beginning in 1979, the St. Father Stanislaw Bogdanowicz was responsible for restoring a significant portion of the medieval movable monuments that had been taken over by Polish and German museums following the war to the interior of Mary’s Basilica. Father Zbigniew Zieliski became the next parish priest in October 2014. He was replaced in December 2015 by Father Prelate Ireneusz Bradtke. The church’s facade was cleaned in 2017 and the roof covering (over 7,000 square meters and approximately 100,000 roof tiles) was replaced. The project cost PLN 15 million gross and was finished in the fall of 2018. The walls were lightened as part of the work by removing the concrete structural elements that had been installed following the war to replace the burned-out wooden ones. At this point, only steel is still present. The bay window in the upper portion of the building, which formerly housed a crane for transporting heavy materials to the attic, was also reconstructed during this time. The stained-glass windows were also restored. A missing turret on the roof was reconstructed, and another was restored to its original shape. The restoration work also allowed for the opening and closing of the wings on the 16th-century main altar. A multimedia room was built in the boiler room, and the 1960s-era raised section in the chancel was removed. The largest basilica renovation since the completion of the church’s reconstruction following World War II lasted three years, ended in 2020, and cost nearly PLN 20 million. In 2019, renovation and conservation of the stone floor began. It is mostly made up of several hundred tombstones that mark the graves of 6,000 people who were buried in the church up until the beginning of the 19th century. Damage to the slabs was caused by factors including war damage (collapsed vaults), geological factors, the passage of time, and the subsidence of former burial sites. In 2020, it was hypothesized that the demolished Gdask Teutonic Castle may have been the source of a stone threshold for the gate that overlooked Grobla Street that was discovered during façade renovation. Similar elements, capital-shaped extensions, can be found at Malbork Castle [19]; the limestone section of the column is divided into two sections that together span approximately two meters. In 2016, the temple was visited by approximately 460,000 people.

Architecture of Co-Cathedral Basilica of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Gdańsk, Poland

Architectural style: Brick Gothic architecture.

Architects: Heinrich Ungeradin, Tylman van Gameren

Burials: Paweł Adamowicz , Maciej Płażyński , Paul Beneke.

St. Mary’s Basilica in Gdańsk has preserved almost entirely Gothic architecture, both in its spatial layout, interior and exterior. The main city parish church is a late style of Brick Gothic, which was popular in the Baltic Lowlands and the Netherlands in the 15th century.

Spatial arrangement

The church is built on an irregular Latin cross plan . It is a hall with three arches and a complex and extensive spatial program. There is a nave with three arches, a choir with three arches, and a false ambulatory that is only identified by the main altar, which is in a bay west of the eastern wall. On the east-west axis, the widths of the nave and choir are identical. There are three naves in the southern section of the transept, while there are only two in the northern section. The need to adapt to the existing urban development led to the transept’s irregular plan in its northern arm. Adjacent to the side naves in all sections of the church are chapels, whose shorter walls serve a de facto structural function; they act as buttresses. Adjacent to the corner of the chancel and the northern arm of the transept is an irregularly planned sacristy. The tower mass, enclosing the church from the west, is formed, along with the square-plan tower, by the flanking side chapels, built on a rectangular plan.

Interior architecture

The uniform height of the individual naves defines the interior. Massive octagonal pillars support vaults with a dense and elaborate ribbed pattern , one of the most characteristic features of late Gothic architecture. The nave and transept feature net vaults , the chancel and some chapels feature stellar vaults, and the side aisles feature diamond vaults , which are devoid of ribs.

External facades

The church’s exterior is dominated by smooth wall surfaces, which feature tall, pointed- arch windows with strongly splayed jambs and modest tracery decoration.The side nave walls are topped with a cornice and battlements. Cornices and gables divide the choir and transept elevations, which are topped by pinnacles. The distinct covering of each nave results in the intricate roof arrangement. Two bell turrets once decorated the ridge of the central roof, which runs over the main nave, transept, and chancel. After the war, only one was rebuilt, the Great Bell, which is at the intersection of the two naves (the second bell turret, weighing 7 tons, was installed on April 28, 2018). The corners are accentuated by eight octagonal turrets, six of which are topped with slender domes (almost all reconstructed after 1970). The Great Ave has the same shape. Each tower has its own name. The first is called Kaletnicza, after a nearby street’s name, and it runs counterclockwise. The next ones are dedicated to saints named after the corner chapels: Kosma, Damian, Barbara, Micha, Jakub (the only one with a wooden interior and original spire), and Kosma. The next two are named Grobla (after the name of a nearby street), and the last tower rises above the Chapel of St. Reinold, hence its name. The 82-meter-high, multi-story tower has a roughly square plan. Unlike the church, it is clasped with massive buttresses that adhere to the corners of the tower’s sides. It has a double-hipped roof over it. There are 409 steps up to the observation deck at the top of the tower. Gdask, the Baltic Sea, and Uawy can all be seen from the deck, as can Gdynia and Tczew as well. The church is accessed through seven portals : one each from the west (Pod Wieżą Gate) and east (Mariacka Gate), three from the south (Kaletnicza, Radnych, Wysoka Gates), and two from the north (Na Groble and Szewska Gates). On the northern façade of the basilica is the Baroque Groble Clock, and on the southern façade are a sundial from 1533 and the remains of an earlier (probably the oldest in Gdańsk) sundial from the second half of the 15th century.

Interior design

The interior decoration is composed of valuable Gothic , Mannerist , and Baroque paintings and sculptures , many of them works of the highest artistic and historical caliber. The preserved works are valuable historical complexes connected to the given historical era, despite the church’s turbulent past. Numerous figures, altar retables, or fragments of them, from both the Teutonic and Polish periods, primarily funded by local burghers who formed Gdask’s elite at the time, provide evidence of the medieval period. Numerous contemporary floor tombstones, pictorial epitaphs, and totenschilds with coats of arms make up the massive historical complex, which reflects the Lutheran atmosphere of the church before it was taken over by the Evangelical community in 1572. Additionally, there is a collection of paintings and sculptures from the Baroque era. After the war, some chapels received modern decorations, a small portion of which demonstrates a high artistic standard. Additionally, components of the interior design of St. John the Baptist Church were reinstalled in the basilica. John (including the baptismal font, pulpit, organ case, and a number of paintings and epitaphs).

Medieval monuments

The oldest works constituting the medieval interior design are a group of sculptures from the Beaux-Arts period (1410–1430): the Beautiful Madonna, the Pietà, St. George Slaying the Dragon, Mary and John in the Chapel of the Eleven Thousand Virgins, and the altars of the Priestly Brotherhood of the Blessed Virgin Mary, St. Hedwig, and St. Dorothy. Several works that once formed part of the church’s interior are preserved in museums, including the Winterfeld Diptych, the Pietas Domini painting from the Holy Trinity Oratory, the retable of the altar of St. Cosmas and Damian, the altar of St. Elizabeth, and the Dormition of the Virgin group. Early Gothic realism is exemplified by the triptych with The Last Judgment by Hans Memling (since 1945 at the National Museum in Gdańsk ). A large ensemble comprises works of sculpture and panel painting from the last two decades of the 15th century: the altar of St. Barbara, the large and small Ferber altars, and the Tablet of the Ten Commandments. The youngest group of medieval works consists of the retable of the main altar, the work of Master Michael and his workshop, works by Master Paul and his circle: the Crucifixion Group on the rood beam and the figure of Christ as Salvator Mundi, and the Antwerp retable of the altar of St. Adrian.

A set of wall paintings

Originally, the church’s interior was covered with polychrome, but since the Reformation, most of the wall paintings have been covered with a uniform white layer of paint. The paintings in the St. Mary’s chapel were destroyed by fire in the western tower during the previous war. Olav, located on the ground floor. In the chapels of St. Peter’s, significant fragments of paintings were discovered during conservation and security work in 1980, 1982-85, and 1988. James, Saint St. George and Hedwig. within the walls of Saint A collection of paintings depicting the chapel’s patron saint, the Virgin Mary’s mercy toward the dead, and Christ as judge were unearthed beneath five layers of whitewash in James’s chapel. In addition, a rare iconographic representation of the Holy Trinity featuring three men seated on a single throne and holding hands. A common cruciform halo covers their heads. A second series of paintings depicting the sequence of events from the Passion, including the Last Supper, the Descent into Hell, and the Resurrection, can be found next to it. St. Peter’s wall George’s Chapel, a late Gothic painting has survived, depicting a view of the city, with densely packed tenement houses of rich architecture, fortifications with towers, a gate, and a drawbridge over the moat. Visible figures include a royal couple interpreted as the parents of St. Margaret , a galloping rider on a white horse, and several knights. During conservation, older paintings dating from around 1400 were discovered beneath this painting. Therefore, the newer polychrome was delaminated, transferred to a substrate, and placed below the sculptural group depicting St. George. The older painting shows a landscape with a river and a rocky hill. On top of the hill is a castle where the royal couple emerges from the windows. A windmill stands on the hillside. Nearby, a bear and a deer can be seen in a small forest. within the walls of Saint Jadwiga’s Chapel are paintings depicting the Crucifixion Group and the enthroned Virgin Mary and Child, accompanied by musical angels. Unknown family members with unknown children kneel at Mary’s feet; seven men kneel on the right and two women kneel on the left. The painting is an epitaph, likely commemorating the chapel’s founders. Saints Jadwiga and Margaret are depicted on the adjacent buttress. All the paintings date to the 1430s.

The main altar

Master Michael of Augsburg and his workshop created the polyptych that makes up the main altar and dates from 1511 to 1517. It has three pairs of carved and painted wings, one of which is set on top of a predella. Numerous times, the retable has been rebuilt and preserved. Reproductions faithful to the originals have taken the place of some of the lost paintings and sculptures. The main altar, measuring 489 x 390 cm, depicts the scene of the Coronation of the Virgin ; on a tripartite throne sit larger-than-life figures of Christ , Mary , and God the Father . The Dove of the Holy Spirit flies beneath the crown of angels that hangs above Mary’s head. The body is framed by a carved vine, on which sit the 24 Elders of the Apocalypse, who hold musical instruments and golden censers , among other things . Twelve of these are authentic sculptures, the other twelve have been reconstructed. 11 of the 144 full-size, small saint figurines that were carved into the carved wings’ obverses have survived to this day. These panels are richly ornamented and serve as a backdrop. Carved panels depict selected themes from Christ and Mary’s lives on the reverse. Scenes from top to bottom in the left wing include scenes of the Annunciation, the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Temple, the 12-year-old Christ in the Jerusalem Temple, and the Resurrected Christ Appearing to His Mother. Scenes depicting the Adoration of the Magi, the Nativity, the Descent of the Holy Spirit, and the Dormition of the Blessed Virgin Mary are arranged in the right wing from top to bottom. The Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary is divided into two panels at the top, both of which are partially damaged. Paintings arranged in the quarters of two pairs of movable and immovable wings, which form the altar’s reverse and are visible from the east, make up the remainder of the retable. On the obverses of the movable wings are colorfully painted episodes from the life of Christ. On the movable left wing from the top: The Flight into Egypt, 12-year-old Christ in the Temple, Carrying the Cross, and The Crucifixion . On the movable right wing, from the top, are the following scenes: Christ Says Goodbye to His Mother, Ecce Homo, Descent from the Cross, Resurrection. On the reverses of the movable wings, painted scenes from the life of Mary and her parents, Joachim and Anne are depicted using the en grisaille technique. On the left wing from the top: The Sacrifice of St. Joachim The Vision of St. Joachim, Mary as a Girl Entering the Temple , The Marriage of Mary . The right wing depicts, from the top: Saint Joachim with Saint Anne at the Golden Gate, Birth of Mary , Saint Joseph at work , Holy Family in Egypt. The fixed wings have two panels, each containing only a single scene. From the top, the obverses feature the Nativity and the Magi’s adoration on the right panel and the Annunciation and circumcision on the left panel. On the reverses – on the top left panel: Christ Appears to His Mother and Doubting Thomas; on the right panel: Noli me tangere and the Descent of the Holy Spirit. The paintings of these scenes are grisaille. The panels on the reverse are enriched with numerous plant motifs and personifications of virtues and planets, as well as ancient figures . The predella depicts the Entombment from 1870. At the back, in the altarpiece’s base, is a stone sculpture from 1536, depicting the Garden of Gethsemane. The retable exemplifies the synthesis of Gothic tradition with the Northern European Renaissance. Both the sculptures and the paintings reveal a synthesis of diverse inspirations from southern German painting and graphic art. The graphics of Albrecht Dürer and Hans Burgkmair significantly influenced the design of individual scenes.

Sacramentary

Situated at the northeastern pillar between the intersection of the naves and the chancel, the sacramentary is a valuable example of microarchitecture, i.e., the art of constructing small structures according to the principles and structure typical of construction. Completed in 1482, carved from wood in the shape of a multi-story turret, its exterior features rich tracery decoration on both the openwork and wood-clad walls, as well as a rich array of architectural motifs typical of Gothic architecture: pinnacles , gables with crockets and finials . Furthermore, there are small sculptures, including figures’ heads, crabs , lions , and, at the pinnacle’s finial , a pelican feeding its young chicks with its blood (one of the symbols of the Eucharist ). The total height of the sacramentary is 8.30 m . On the inside of the door of the room for the Blessed Sacrament there is a painted representation of Christ as Salvator Mundi.

The beautiful Madonna of Gdańsk

The sculpture of the Beautiful Madonna is a full-scale work of art carved from soft sandstone by an anonymous artist. With a red-and-gold Baroque robe, a blue cloak with gold trim, and golden hair, it was repainted during the Baroque era. Earlier, around 1515–1520, radiant sheet metal ornaments were added. It is on display in the Saint Chapel. Like it did in the Middle Ages, Anne and serves as a cult sculpture as well as a private devotional object. It is one of the cult sculptures of the Mary and Child, known as Beautiful Madonnas, characteristic of the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, representing the Virgin Mary and Child, pars prototo of International Gothic. Artistic historiography contains numerous discrepancies regarding the origins of the form, authorship, and time of creation of the Gdańsk Beautiful Madonna. The sculpture of the Beautiful Madonna of Gdask was believed to have been created by an artist from the circle of the Master of the Beautiful Madonna of Toru, who was also to create other sculptures for the Gdask parish church. This was because the style of the figures and robes shared a number of similarities. The Gdańsk work was associated with Beautiful Madonnas from Bonn , Sternberk in Moravia, and Stralsund, among others, stylistically related to the lost figure from Toruń. Due to the French-Dutch origins of the form, which deviated from the classical canon of the Beautiful Madonna, these assumptions, which had been accepted in the literature for a long time, have recently been questioned. Therefore, the dating to c. 1410 has been revised in favor of a later date of c. 1410–1430. The current altarpiece was created between 1515 and 1520, alongside which the older statue was placed. The statue’s background is a radiant glory and a wreath of roses with interwoven medallions depicting scenes from the Passion. The narrative begins with the Last Supper, followed by the Prayer in the Garden of Olives, the Flagellation, the Crowning with Thorns, the Stripping of the Garments, the Crucifixion, and the Lamentation. Under the awning of the altarpiece is a medallion depicting the Holy Trinity in the form of three men seated on a single throne, united by a common halo and holding hands. Two groups of kneeling figures represent the Church as the People of God at the bottom, on either side of the rosary wreath. On the right are clergy from all hierarchies, and on the left are laypeople from all social classes. There are images in the upper corners. St. Adalbert and St. Francis.

Heel

Hauptartikel: Pietà in St. Mary’s Cathedral in Gdask The gigantic Pietà in Saint Reinold’s Chapel, dating from around 1390 (1.45 m high), is the work of an unknown artist, formerly also credited with the Gdańsk Beautiful Madonna. Stylistically, it fully reflects the conventions of International Gothic, which saw a shift in the depiction of the Pietà, abandoning expressiveness and dolorism in favor of elegance and sublimation, minimizing the dramatic content. The fluid and dynamic arrangement of the folds of the garments, the delicate modeling of Mary’s face and Christ’s body, and the realistic depiction of Mary’s relationship with Christ, in which concern and pain are combined with prayerful adoration, attest to its high craftsmanship. The work was probably created by a sculptor from Gdańsk, and its form reveals inspiration from the Silesian trend of the beautiful style, as well as from the Pieta from Baden (located until the last war in the Kaiser-Wilhelm Museum in Berlin) and of unknown origin (currently in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg).

Crucifixion group on the rood beam

On a beam placed between the two eastern pillars of the nave crossing there is the Crucifixion Group; in the centre there is a crucifix of supernatural size (height 4.5 m). On its sides are figures of Our Lady of Sorrows (3.5 m) and St. (3.6 m) John the Evangelist Master Paul, a woodcarver, created these polychromed, hollowed-out, solid wooden figures in 1517 with funding from Ketting.

Crucifixion Group in the Chapel of the Eleven Thousand Virgins

The group of crucifixions in St. Mary’s Cathedral in Gdask The Crucifixion Group, which consists of a crucifix and two statues of Mary and John the Evangelist, can be found at the Chapel of the Eleven Thousand Virgins’ eastern buttress. The linden wood figures represent a beautiful style, as evidenced by the delicately modeled faces and flowing drapery of their robes. There are also features attesting to Gothic realism, including the emphasis on facial features and emotions. The polychrome colors, facial expressions, and anatomy of the Crucified figure exhibit a strong emphasis on realism. His face gives the impression of a real person going through the dying moment. A late Gothic predella from the late 15th century below the figures features portraits of Christ and the Twelve Apostles. The sculptures of Mary and John date to the 1420s, while the dating of the crucifix has been the subject of much debate among scholars (hence the discrepancies between the 15th and 17th centuries). Based on the formal connections between the Christ image and the realistic paintings of the early Netherlandish primitivist generation, recent research on the work questioned its 17th-century date and accepted the 1430s as the creation year.

Saint George fighting the dragon

Three full-scale figures of the patron saint, the dragon, and Princess Margaret are placed against the wall of St. George’s Chapel. They are integrated into the background, creating a wall painting with a landscape and architectural setting, characterized by deep space (primarily the tower with the royal couple interpreted as Margaret’s parents). The sculptures (with partially preserved polychromes) originate from a Gdańsk workshop and date to around 1400. Partially damaged in 1945, they underwent extensive conservation after the war.

Altar of the Holy Trinity

The altarpiece was founded by the Brotherhood of St. George, which had its own chapel in St. Mary’s Basilica, located on the west side of the northern arm of the transept. The work was created around 1430. In its present form, it consists of a double-sided painted image and a predella. The obverse depicts the Holy Trinity in the Pietas Domini style. The reverse depicts King Arthur and the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order. The predella depicts the Holy Trinity in the Throne of Grace style , flanked by Saints George and Olaf. Before 1942, it was located by a pillar opposite St. George’s Chapel. After 1945, it was considered lost, and only around 2000 was it determined that, beginning in the 1970s, the painting had been acquired by one of Berlin’s Protestant communities. The painting was transferred to the state collections in Berlin (previously the Bode Museum , then the Gemäldegalerie ) as a deposit. The predella was located in the Church of St. John in Berlin-Moabit (the work of K.F. Schinkel ). In 2020, the decision was made to return the painting and the predella to the original church and place them on the altar mensa in the northern arm of the ambulatory, at the entrance to the sacristy.

Altarpieces of St. Mary’s Basilica in Gdańsk

The Altar of the Priestly Brotherhood of the Blessed Virgin Mary was funded by a brotherhood that had been active since 1385. Around 1470, they commissioned a retable for their chapel. It was designed as a cabinet that could be closed and opened like a triptych. A statue of the Virgin Mary and her Child that is older than the others and resembles the Beautiful Madonna style can be found inside. When the wings are open, you see four holy virgins Barbara, Catherine, Dorothy, and Margaretpainted on the shorter sides. The panels on the wings show six scenes: the Annunciation, the Visitation, the Nativity, the Adoration of the Magi, the Presentation in the Temple, and the Flight into Egypt. The cabinet depicts various scenes from Christ’s Passion when it is closed. The predella, which dates from the late 15th century and depicts Mary holding the Child on her lap and being crowned by angels, supports the altar. Six beautiful robed prophets Habakkuk, Zechariah, Hosea, Obadiah, Micah, and Malachiare positioned around them. The Saint’s Altar Between the years 1480 and 1500, the apprentice shoemakers paid for Barbara’s production in Gdask. It is a carved pentaptych, which means that it has both carved and painted parts in its five main panels. In the center is a statue of St. Barbara with a crown of angels on her head. The moveable wings have carvings of Saints John the Baptist, James the Apostle, Hedwig of Silesia, and Thomas of Canterbury. The outer panels, both front and back, are painted with scenes from Based on a legend by Simon Metaphrastes, St. Barbara’s life. The predella shows the Annunciation in the center, and on either side are Saints Barbara, Catherine, Dorothea, and Margaret. The Altar of St. Adrian stands in the Chapel of the Holy Cross. It’s an Antwerp work from around 1520, built like a polyptych with those tall, arch-shaped panels you often see in Antwerp retables. The center and inner panels are carved, while the rest is painted. Christ carrying the Cross, the Crucifixion, and the Lamentation are the three primary carved scenes. The side panels include the Empty Bed, the Annunciation, the Birth of Christ, the Adoration of the Magi, the Circumcision, and the Escape into Egypt. The painted parts focus on scenes from the Passion. The altar sits on an older predella made in Gdańsk around 1460–1470. It shows the martyrdom of St. Adrian and his companions in Nicomedia, with his wife Natalia watching. Saints Simon and Jude Thaddeus are situated either side of the predella. The Altar of St. Dorothy is in St. George’s Chapel. It was made around 1435 and combines five alabaster panels from England with painted wings done in Gdańsk. The Resurrection occupies the center of the alabaster scenes, with the Nativity on the left and the Descent of the Holy Spirit on the right. Two smaller alabaster panels show John the Baptist and the Annunciation on one side, and the Coronation of the Virgin with John the Evangelist on the other. The tales of Saint tell in the painted wings. Agatha and St. Catherine. Agatha is tortured in a cauldron and has her breasts cut off, and Catherine is beheaded after destroying a pagan altar. There is a scene from Saint The life of Dorothy, including her miracle with the roses and Theophilus’ conversion. The predella depicts the Annunciation, and the reverse side features Christ’s face surrounded by a yellow circle and a red cross halo. The Large Ferber Altar was funded by Barbara and Jan Ferber around 1481–1484. Despite the absence of the central Crucifixion scene, the remainder is still impressive. The top wings show the Visitation of Mary and the figures of Saints Dorothy and Margaret. John the Baptist and John the Evangelist can be found in the side wings. Below them is the Ferber family, which consists of the parents kneeling alongside their ten sons and one daughter. On the reverse of the wings is an Annunciation scene with Mary and the Angel. The saints Constantine and Helena are depicted on the fixed side wings. Two paintings from the predella are still around: one shows Saints Reinold and Giles, and the other shows John the Baptist with Saint Sebastian.The Small Ferber Altar was painted around 1485 by a Gdańsk artist and was also funded by Jan Ferber. A church is the setting for the central scene. Arma Christi, or the instruments of the Passion, are held by angels around Christ, who is depicted as the “Man of Sorrows” or Vir Dolorum. Mary and John the Evangelist are seated at the feet of the Ferber family on the side wings. The church setting is maintained by the background. The back of the wings shows the Annunciation, and the fixed wings have Saints Peter and Paul.

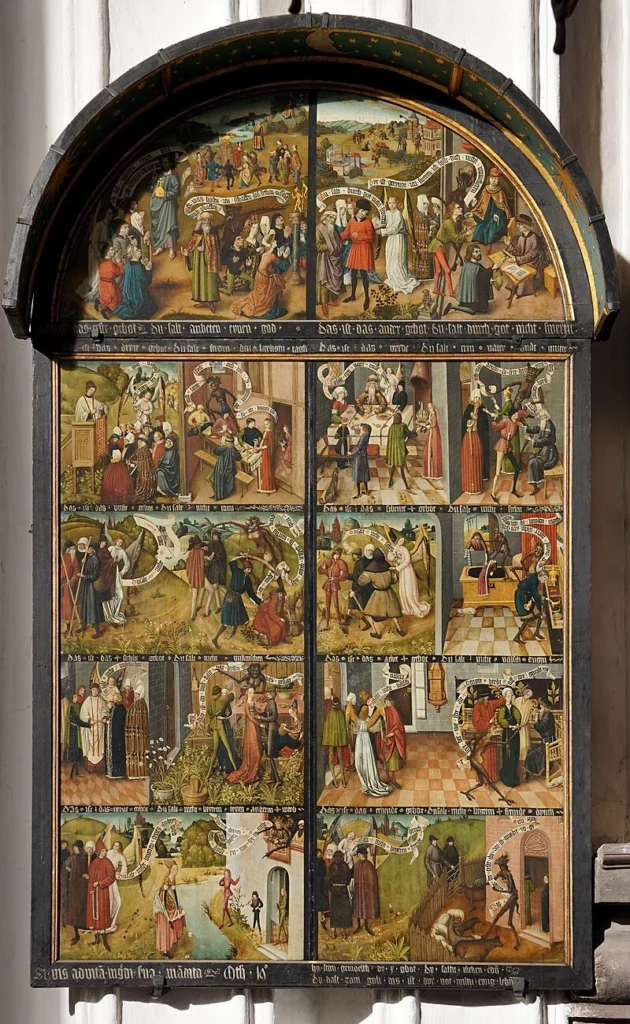

Tablet of the Ten Commandments

It was painted by an unknown master between 1480 and 1490, and it has ten painted panels with two genre scenes of virtues and vices in the context of the Ten Commandments. A corresponding proverb is inscribed on a banderole in Old German minuscule, and each scene depicting the observance of a commandment is accompanied by an angel, while the scene depicting the breaking of a commandment is accompanied by a devil. The panel is one of the earliest pictorial representations depicting the practice of observing the Ten Commandments in everyday life. The First Commandment Believe in the One God is illustrated by figures kneeling before the blessing Christ and two groups of people committing the sin of idolatry: those adoring an idol placed on a column and those dancing around a golden calf. The contrast between two values: true and false faith. The image of a group of people participating in a court trial depicted in the Second Commandment, “Thou shalt not take His name in vain,” is that of a cross on the bench. The judge taking testimony and the taking of an oath are two distinct scenes in the trial. Perjury and orthodoxy are contrasted in this. Third Commandment – Keep the holy day holy, Sunday holy the faithful listening to sermons and reveling in taverns, accompanied by gluttony, drunkenness, and impurity. Listening to sermons was a highly valued form of piety. The fourth commandment Honor your father and your mother a feast at the table where children serve the family, and a daughter and son beating and slandering their elderly parents. The Fifth Commandment Thou shalt not kill pilgrims walking along a road, with a younger one helping the older ones along the way, and a scene of two murders, one treacherous and the other for robbery. Medieval pilgrimage, like travel, involved the risk of danger, so the scene illustrates the Christian’s courage and his help for the weak. The Sixth Commandment You shall not commit adultery a marriage ceremony and three couples having a voluptuous time, two dancing, one embracing. The juxtaposition of modesty, moderation, and the honors that marriage brings to spouses is contrasted with the licentiousness of marital infidelity. The Seventh Commandment You shall not steal is represented by a man holding an axe one of the symbols of work hereand two thieves stealing valuable items from a bedroom despite the gallows with three hanged men visible through the window a symbol of punishment and warning. contrasting the wicked acquisition of wealth with diligence. The Eighth Commandment You shall not bear false witness two men falsely accusing a young woman to her elderly husband, and the truthful witnesses who leave the room where the testimony was taking place. a nod to the biblical incident involving Susanna and the elders. A young, ornately dressed woman standing by the riverbank, her leg bare above the knee, arouses the desire of the king and a large group of men looking out the window, just like an angel with a group of praying travelers does the Ninth Commandment. a contrast between beauty that is alluring and vain and simplicity. a reference to the biblical scene of David and Bathsheba. The heirs and family of the deceased viewing his possessions, as well as a group gathered to pray for the deceased, all violated the Tenth Commandment, which says, “You shall not covet anything that belongs to your neighbor.” The juxtaposition of respect for the deceased with the desire to seize his inheritance.

Astronomical clock

The clock that tells the time in St. Mary’s Church was built by Hans Düringer from Toru between 1464 and 1470 on the basis of a contract with Henryk Hatekann. The contract was signed on 1 May 1464, and the cost of the work was estimated at 300 marks and 6 Hungarian guilders. Later, some in-kind benefits, most notably a house on Holy Spirit Street, added to the costs. For nearly seven years, Hans Düringer worked, often with his son. The finished piece was over 14 meters tall, had six distinct mechanisms, and it had three floors: a calendar, a planetarium, and a theater of figures. The clock became an object of admiration for guests from all over Europe. Legend has it that when the Lübeck authorities asked the Toruń master to make another clock, jealous councilors, acting on the orders of Mayor Konstantyn Ferber, ordered the master blinded. The blind master was asked to fix the clock when it broke years later. He hit the mechanism of the clock with a hammer, cursed, and then fell to the church floor and died instantly. By 1554, the clock was out of order and fell into oblivion. It was taken apart at the end of the war, and 70 percent of the outer casing was found and given back to the church. The Social Committee to Rebuild the Astronomical Clock was established in 1983. Associate Professor Andrzej Januszajtis was in charge of it. On March 16, 1987, the clock case was placed in its original location. A number of sculptures were also reconstructed. An effort is currently being made to get the clock working again.

Modern monuments

The Reformation heralded the modern era of art in Gdask and the Baltic Sea basin. Martin Luther and John Calvin’s teachings had an impact on this region, and in 1572, Gdask’s Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which was originally a biden, became a Protestant church. The Lutheran patricians who were in charge of the church kept the main altar and other medieval artifacts while redesigning the interior in accordance with liturgical structures. They started building the organ, the baptismal font, and a large collection of memorials, including pictorial epitaphs, tombstones, and the coats of arms of deceased burghers (totenschilds). Both of these structures are still in use today. These are mostly works by Gdask artists who are familiar with Dutch and German Mannerism. The Bahr tombstone represents the transition from Mannerism to Baroque . Single paintings (including the Alms Board), a group of figures, benches, and chapel fences date from the 17th and 18th centuries.

Pulpit

The former Rococo pulpit , designed by Johann Heinrich Meissner in 1762, was destroyed in 1945. The current Mannerist pulpit comes from St. John’s Church in Gdańsk. It was built in 1616/17. It consists of a basket with stairs leading up to it, which rests on a single pillar, and a canopy with a lantern. Made of oak, polychrome, and adorned with oil paintings (attributed to Isaac van den Blocke ) and richly sculpted decoration. The doorway, framed by an ornate portal, before the stairs features a painting of Christ as the Good Shepherd. The background is a sheepfold, with a scene of two thieves stealing sheep. On the reverse is a painting depicting the death of Nadab and Abihu, sons of Aaron. The portal is crowned by figures of Christ and personifications of Faith and Hope . On the stair balustrade are rhomboidal panels with paintings depicting the Miracle at Troas , St. Paul’s Sermon in Athens , the Parable of the Good Shepherd , the First Conflict with the Pharisees , Christ Teaching from a Boat , and the Calling of the Apostles Peter and Paul . The pulpit basket has a hexagonal plan. Its outer walls are decorated with four paintings: The Conversion of the Ninevites , The Institution of the Feast of Tabernacles , The Reading of the Book of the Law of the Lord before King Josiah, and Noah Receives the Commandment from God to Build the Ark . Three of these are modern reconstructions by Aloysius Osada. The canopy is decorated with figurines of women, allegories of Fear of God, Wisdom, Joy, Love, Peace, and Piety. Inside the lantern is a full-body sculpture of St. John the Baptist. On the lantern’s cupola there is a carved Phoenix in flames, with spread wings, a symbol of the sacrifice and Resurrection of Christ.

Baptistery with baptismal font

The original baptistery, consecrated in 1557, is partially preserved, due to the loss of the basin and elements of the fence during the turmoil of war. The creators of the former baptistery included Cornelius Hohe, Heinrich Neuborg, Bartel Pasteyde (the fence plinth), and Hinrik Wyllemson (the baptismal font). The octagonal plinth of the fence is decorated with reliefs carved in Gotland stone, depicting the Procession of Mercy , the Baptism of Christ in the Jordan , the Baptism of the Queen of Egypt’s Courtier , the Vision of St. Peter and the Baptism of Cornelius , and the Crossing of the Jews through the Red Sea . At the base of the basin stand bronze figures representing allegories of Generosity, Resolve, Mercy, Faith, Hope, Temperance, Wisdom, and Justice. At the feet of the basin are bronze figures of the Evangelists: St. Mark and St. Luke (the others are lost). The current baptismal bowl comes from the Church of St. John. It was created in 1682 thanks to a foundation by Katharina Zappio. It is made of wood and clad in gilded copper sheet, with repoussé ornaments and figures of the Evangelists and four biblical scenes. The bowl’s cover is surmounted by figures of Christ and John the Baptist, creating a scene of the baptism in the Jordan. After 2005, the baptismal bowl was returned to its historic location. A 20th-century plaster cast of the former baptismal bowl is located in the Chapel of St. George.

Organs

In place of the organ case from 1586 and 1760, destroyed in 1945, an early Baroque case from 1629 from St. John’s Church was installed between 1981 and 1985. The surviving fragments of the old case were placed in several places in the basilica. The new instrument was made by the organ-building firm of the Hillebrand brothers from Hanover . Teams of social activists and specialists from Poland and Germany collaborated on this project, with Dr. Otto Kulcke from Oberursel initiating the restoration of the organ to the Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The organ was consecrated on August 18, 1985.The instrument has 46 stops and a full mechanical tracker , modeled on the old Friesen instrument. The entire material is arranged spatially in four sections: Hauptwerk – 11 stops, Brustwerk – 10 stops, Rückpositiv – 12 stops, and Pedal – 13 stops arranged in two symmetrical pedal towers.

Bahr tombstone

Abraham van den Blocke created the Szymon and Judyta Bahr tombstone, which dates from 1614 to 1620. Johann Speymann, the mayor of Gdask and the Bahr’s son-in-law, commissioned the work. It is made of alabaster, limestone, and marble in a variety of colors, and some of the details are gilded. A narrower tomb stands on a double plinth, topped by a wide, profiled cornice, supported in the corners by free-standing columns. On the slab covering the entire structure, between obelisks placed in the corners, kneel the married couple Judyta and Szymon Bahr, facing each other in prayer. Between them is a double-sided cartouche with the Rawicz coat of arms . A huge inscription plaque covers almost the entire front of the tomb.

Alms Board

The Alms Board is a work created in 1607 by the Gdańsk painter Antoni Möller . It owes its name to the collection boxes that once existed beneath the painting, into which donations for the poor were deposited. The work consists of three closely integrated parts, enclosed by a decorative frame. The lower part is formed by a stone base, on which are inscriptions with verses of Scripture referring to mercy and a poem encouraging generosity for the poor. The central part depicts the Allegory of Faith a reclining woman adoring the cross. Beside her lie an open Bible and a golden chalice of wine. From her heart grows a tree trunk, and on its crown stands a charming woman holding a child in her hand, an allegory of Mercy, accompanied by four other children. Two of them personify concord and peace, the others war and discord. From beneath her heart grows a branch, part of the symbolic Tree of Mercy, whose branches are topped with circular medallions depicting the seven corporal works of mercy. The medallions’ content constituted the idea and gave the work its specific function: encouraging the faithful to make donations to support shelters, schools, and hospitals for the poor, to provide clothing and food for the poor, and to pay for funeral services. The panel is crowned by a painting on semicircular board depicting the Last Judgment. Surrounded by Christ, Mary, and the apostles, the Archangel Michael, depicted as a shepherd, separates the sheep from the goats.

Epitaphs in St. Mary’s Basilica

In the St. Mary’s Chapel Mary Magdalene, Michael Loys’s obituary is here. It was made in the Netherlands in 1561 and has the shape of a triptych, with his coat of arms and the initials “MLF” carved into the triangular top. All of it is displayed in a painted wooden frame. Two alabaster panels depicting the Crucifixion and Resurrection can be found in the middle. The third scene, the Descent from the Cross, used to exist, but it was lost in 1945. On top of the whole thing, there are two small sculptures representing Faith and Hope. Near the Councilors’ Gate, on one of the big walls, is the large epitaph of Johann and Dorothy Brandes. It was made in 1586 by Willem van den Blocke. A large stone plaque with writing in the middle is flanked by two carved women balancing the structure, again representing Faith and Hope. The Brandes couple praying can be seen above them in tiny niches. They are surrounded by additional figurative representations of peace, immortality, and perseverance. A figure of Death with a scythe and an hourglass at the top is surrounded by symbols of both royalty and common people, including a shovel, scepter, sword, and scythe. Within the space between the St. Balthazar and St. Anthony, another piece by van den Blocke is the 1591 epitaph of Edward Blemke on the eastern wall. Based on Ezekiel’s vision, it depicts the resurrection of the dead in the Valley of Josaphat. Ezekiel can be seen standing in the middle, and skeletons are slowly turning back into people around him. Above the scene, up in the clouds, there’s the name of God and four angels blowing wind toward the earth. It is surrounded by two columns, and carvings depicting Justice and Prudence can be found on either side. The piece also has numerous little angels carved in and scattered about. Then there’s the epitaph of Jacob Schadius, made in 1612, probably by someone from Antoni Möller’s circle. This one is more oval-shaped and tells the same story as Ezekiel: the prophet, the people who have died, and donors praying nearby. The whole thing has a lot of movement the prophet’s robe looks like it’s caught in the wind, and the bodies are really animated. Another one worth seeing is the epitaph of Bartolomeus Wagner from 1571. It is divided into three sections: the bottom has a painting of the Wagner family, the middle has a painting of Christ’s resurrection, and the top has carved angels holding a globe in their hands. The central image is framed with sculpted putti and standing female figures typical of the style back then. Last but not least is Hans Caspar Gockheller’s epitaph for Johann Schröder, written sometime between 1665 and 1675. This one is made of black marble and features white alabaster sculptures, giving it a more Baroque appearance. In the middle, there is a bust of Schröder in clerical attire, and on either side are figures of Faith and Hope. There’s also a coat of arms and some very detailed carvings garlands, little decorations, and so on that show off the skill of the sculptor.

Modern Additions and Memorials in St. Mary’s Basilica

As time went on and the church was gradually rebuilt, some chapels were given newer designs. A few modern altars were added, like the ones for Our Lady of Częstochowa and Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn. The walls now hold many plaques remembering people who gave their lives in World War II people like Major Henryk Sucharski, the defenders of Westerplatte, Home Army soldiers, and also Solidarity members and others tied to Gdańsk’s past. These additions were made out of respect, but not everyone was happy with how they looked. Some art experts and conservators think that certain elements don’t really fit with the old church especially the Smolensk disaster monument, which has been criticized for being too big and for not matching the style of the place. Raising the chancel floor and parts of a few chapels also changed the way the space feels, and some say it disrupts the Gothic character of the interior. One of the most meaningful spaces added in recent times is the Chapel of the Sea People. It’s set in what used to be the All Saints’ Chapel, which was once a library up until 1912. In 1980, Andrzej Bohomolec who was the first Pole to sail across the Atlantic before the war on a boat called “Dal” helped make it into a place to remember sailors, fishermen, and others who died at sea. There’s a statue of the Virgin Mary, Queen of the Seas and Oceans, and the decorations show sea-themed Bible scenes. Local artists from Gdańsk Stanisław Konieczny and Janina Karczewska-Konieczna created the interior. The chapel’s entrance is framed by an old Baroque portal from the 17th century. Another important space is the Priests’ Chapel. Since 1965, it’s been a memorial to nearly 2,800 Polish priests killed during the war by the Nazis and the Soviet NKVD. Inside, there’s a statue of Christ in sorrow, carved out of red granite by Janina Stefanowicz-Schmidt. You’ll also find a bronze plaque and decorative ironwork listing where the killings took place and how many priests died in each region. In St. Dorothy’s Chapel, on the north wall, there’s an altar to Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn. It was funded by people who used to live in Vilnius. The altar was made by Jan Borowski and includes a replica of the famous painting, decorated with silver and goldwork that features symbols of Mary and lines from the Litany of Loreto. One of the more recent projects was the Stations of the Cross, made between 2005 and 2006. These were the first Stations added to the church in over 60 years the last ones were removed when Protestants took over. The new ones are bronze reliefs, made by sculptor Giennadij Jerszow, who has Polish and Ukrainian roots. There are fifteen plaques in total, each one donated by a different sponsor, whose name appears on a small golden plate next to the station. The set was officially blessed on August 15, during the Feast of the Assumption of Mary the church’s patron day. They’re mounted on pillars along the main aisle, where old Lutheran paintings used to hang. And in 2010, on November 13, a monument to the victims of the Polish plane crash in Smolensk was unveiled in St. Dorothy’s Chapel. It was designed by sculptor Andrzej Renes. Nearby is the tomb of Maciej Płażyński, one of the people who died in that crash.

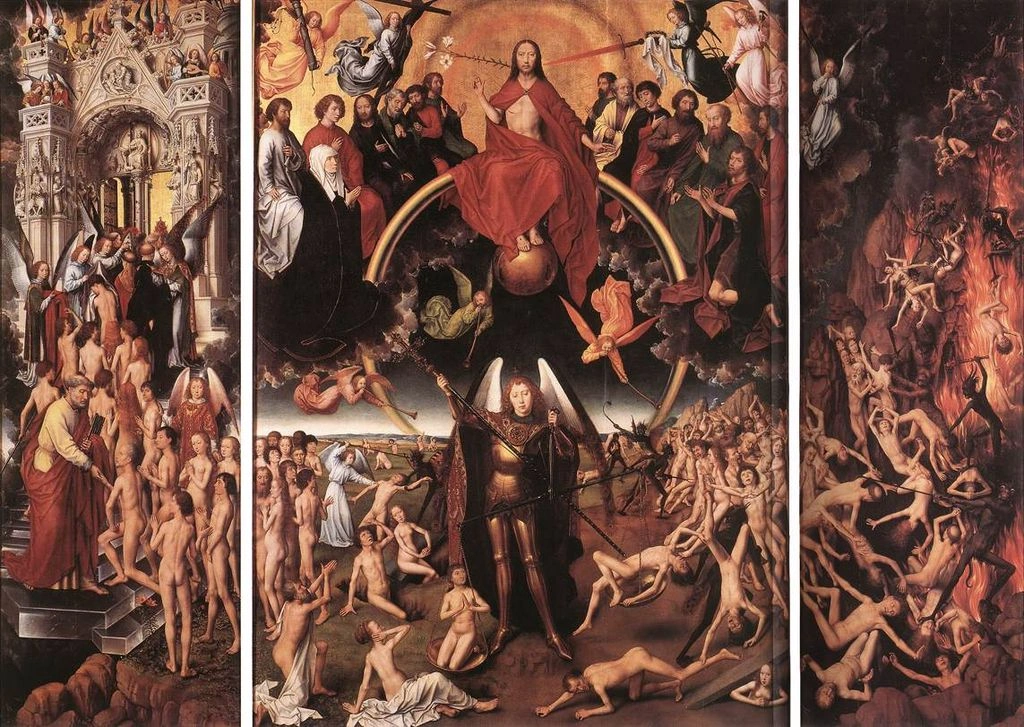

The Last Judgment by Hans Memling

The most valuable work associated with St. Mary’s Church is the triptych “The Last Judgment” by Hans Memling (1467–1473). Since 1956, it has been part of the collection of the National Museum in Gdańsk ; in the church, in the chapel of St. Reinold, near the tower, there is a 19th-century copy. The central part is formed by the title scene, which is divided into two zones: in the upper center, Christ is enthroned on the globe, accompanied by Mary, John the Evangelist, and the apostles; at the bottom, Michael the Archangel judges the crowd of resurrected people, issuing a verdict of salvation or damnation. The left wing shows the symbolic gate to heaven, through which the saved pass. On the other side, hell is shown, where the damned are thrown. On the reverses there are depictions of the Madonna and Child and the Archangel Michael , at their feet kneeling the founders of the retable Angelo di Jacopo Tani and his wife Catherine of Tanagli.

Altars and Devotional Art from St. Mary’s Church That Found a New Home

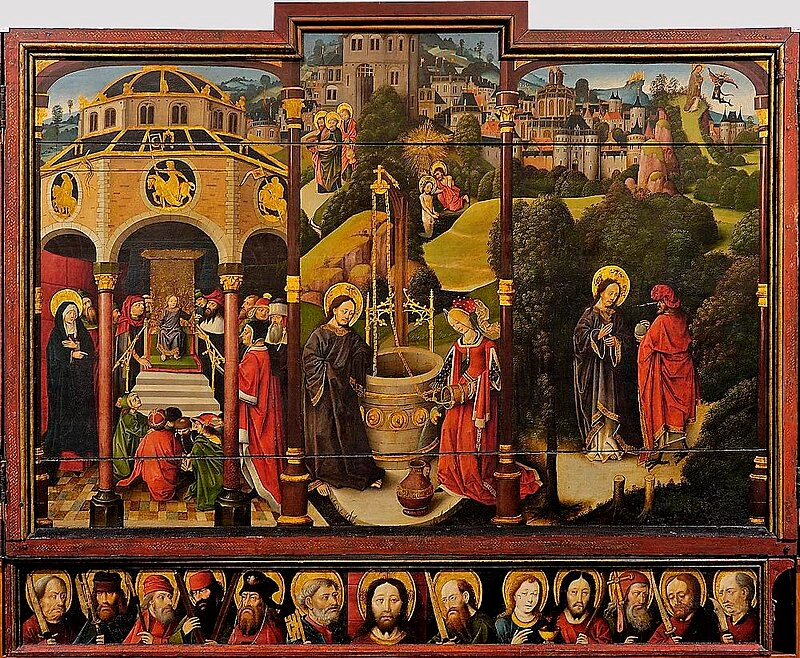

The Altar of Saint Reinold, made in 1515, came from an Antwerp workshop and was made for the Brotherhood of St. Reinold for the chapel they built in St. Mary’s Church in Gdańsk. It’s a big, five-part piece (called a pentaptych), with two sets of wings that could open and close. The carvings were probably done by Jan van Molder, and the painted panels are thought to be the work of Joos van Cleve. The paintings depict scenes from Christ’s life, while the sculpture section tells the story of Mary. The carving style is very typical of late Gothic Antwerp work, but the paintings also mix in some early Renaissance elements. After the war, the altar ended up in the National Museum in Warsaw. The Jerusalem Triptych, painted around 1497 by an unknown artist, used to hang in the Jerusalem Chapel, which is on the south side of the transept. It is a detailed, busy piece that simultaneously tells multiple stories. Right in the center, there’s Jesus as a 12-year-old in the temple, then Him talking to the Samaritan woman, and the Temptation of Christ all happening in one frame, with Jerusalem in the background. The side panels depict events such as Christ entering Jerusalem and ejecting merchants from the temple, the Holy Family fleeing to Egypt, and the children being killed by Herod’s men. If you turn the wings around, you’ll find scenes from the Passion, including the Last Supper and His burial. It tries to show why Christ’s teachings are important and connects it all to the Eucharist, where the bread and wine represent His body and blood. It’s now also in the National Museum in Warsaw. The Winterfeld Diptych, which dates from around 1430, follows. It was obtained from the St. James, whose funding came from the Gdask Winterfeld family. It’s got a fixed wing and a part that opens and closes. When it’s closed, you see Christ being mocked, whipped, and mourned after His death. Open it up, and you’ve got smaller panels showing Mary breastfeeding Jesus (Maria Lactans), Christ as Vir Dolorum (Man of Sorrows), Ecce Homo (Behold the Man), and Mary Magdalene being carried by angels. The artist isn’t known, but it’s thought to have been someone local from Gdańsk. After the war, this one also ended up in Warsaw.

Picture of Pietas Patris

The painting known as the Pietas Patris was once the centerpiece of the shoemakers’ guild altar. In 1944, the side panels that showed angels holding the instruments of Christ’s Passion were lost. The central, preserved panel depicts the Holy Trinity in the Pietas Patris style , with the crowned God the Father lifting the dead body of Christ, over which the Dove of the Holy Spirit hovers. Christ is depicted on a globe. The backdrop for the depiction is an ornate curtain held by four angels. The work was created around 1435 by a Gdask artist who was familiar with Bruges paintings. A second, nearly identical version of the Pietas Patris, produced around 1430 and supported by the Brotherhood of St. George, was located in a church in Gdańsk . Right next to St. George’s Chapel was thought to have been lost after 1945. It wasn’t until around 2000 that it was discovered that one of the Protestant communities in Berlin had been collecting the painting since the 1970s. It was held in state collections in Berlin (previously in the Bode Museum , then in the Gemäldegalerie ) as a deposit. The decision to return the painting to Gdask was made in 2020.

Other Surviving Pieces and Forgotten Treasures from St. Mary’s Church

Before World War II, St. Mary’s Church still had a bunch of other treasures too. There was a canopy altar from the Chapel of St. Cosmas and Damian, dating back to around 1420 it’s now in the National Museum in Warsaw. Two large bells from the 1700s named Dominicalis and Osanna were taken to Germany and now ring in the Churches of Our Lady in Lübeck and St. Andrew in Hildesheim. Lübeck also holds a number of church vestments and fabrics that originally came from here. The National Museum in Gdańsk holds quite a lot too things like chalices, altar tools, and garments from the 15th to 18th centuries. Some items had already been handed over to the Gdańsk museum even before the war, like the Lamentation Altar (also called the St. Elizabeth Altar) from around 1390, carved with scenes of the Pietà, Mary Magdalene, and St. Elizabeth. There’s also the Small Winterfeld Diptych, painted in 1490, which had vanished for a while but showed up not long ago in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. There are also a few pieces that people believe came from St. Mary’s, even though the records don’t officially list them. One is a mid-14th century painting of Mary in childbirth (also called Maria in puerperio), now in the National Museum in Gdańsk it came from the town of Hel. It shows Mary lying on a kind of maternity bed, with the baby Jesus beside her. That kind of image was really popular in medieval monastic and devotional circles but wasn’t accepted under Lutheranism, so it might have been moved out of Gdańsk during the Reformation. Then there’s the Reliquary of St. Barbara, made in 1514 and now kept in the Diocesan Museum in Pelplin. It originally stood in a church in Piaseczno and was probably donated by the Merchants’ Guild. The piece shows St. Barbara with her usual symbols a tower with Jesus inside and a sword and below her are little figures of saints, including St. Sigismund, which was probably a nod to the then-king, Sigismund I the Old. Finally, there’s the sculpture called The Last Prayer of the Virgin Mary, which shows Mary’s death (also known as the Dormition). It was carved around 1400 and was likely the center of an old altar that no longer exists. No one’s sure where it originally came from, but some research suggests it was part of the decoration in the Teutonic Castle in Gdańsk. The Teutonic Knights had a huge devotion to Mary, especially her Dormition and Coronation, which they used to promote their own authority in Pomerania. After the castle was destroyed in the Thirteen Years’ War, the sculpture somehow ended up over the Shoemaker’s Gate at the church. In 1927, the wooden original was taken down and replaced with a stone version. The original is now in the National Museum in Gdańsk.

Bells

There are two bells in the bell tower : Gratia Dei with a striking tone of F sharp 0 and a weight of 7,850 kg, cast in 1970 in the bell foundry of Jan Felczyński in Przemyśl , and a smaller bell, weighing 2,600 kg, Ave Maria , with a striking tone of C sharp¹ .In 2018, a 60-kg bell with the inscriptions “My name is St. John Paul II” and “In eternal memory of the visit of the Polish Pope to St. Mary’s Basilica in Gdańsk on June 12, 1987, Anno Domini 2018” was placed in the reconstructed bell tower, which is to strike the full hours in synchronization with the 17th-century Groblowy Clock . The two bells, which were taken from St. Mary’s Church during World War II: Osanna currently located in St. Andrew’s Church in Hildesheim and Dominicalis in St. Mary’s Church in Lübeck.

Feast Day

Feast Day : 15 August

The feast day of the Co-Cathedral Basilica of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Gdańsk is celebrated on August 15th. This marks the Solemnity of the Assumption of Mary, the church’s patron. It is a deeply spiritual occasion for both the parish and visiting pilgrims.

Church Mass Timing

Monday to Saturday : 7:00 AM, 7:30 AM, 8:00 AM, 6:00 PM, 7:00 PM.

Sunday : 8:30 AM, 10:00 AM, 12:00 PM , 4:00 PM, 6:00 PM, 7:00 PM.

Church Opening Time:

Monday to Saturday : 9:00 am, 5:00 pm.

Sunday : 1:30 pm, 5:00 pm.

Contact Info

Address : Gdańsk Cathedral

Podkramarska 5, 80-834 Gdańsk, Poland

Phone : +48 58 301 39 82

Accommodations

Connectivities

Airway

Co-Cathedral Basilica of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Gdańsk, Poland to Gdynia-Kosakowo Airport, distance between 44 min (37.4 km) via S6.

Railway

Co-Cathedral Basilica of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Gdańsk, Poland, to Gdynia Hill of St. Maximilian distance between 40 min ( 31.7 km )via Aleja Armii Krajowej and S6.