Introduction

Santo Domingo de Silos Abbey (Spanish: Abadía del Monasterio de Santo Domingo de Silos) is a historic Benedictine monastery situated in the village of Santo Domingo de Silos, in the southern region of the Province of Burgos, within the autonomous community of Castile and León, northern Spain. Nestled in the tranquil Tabladillo Valley—so named in the earliest surviving document from the Silos Archive dated 954—the abbey occupies a secluded location in the eastern part of the valley. Originally known as the Monastery of San Sebastián de Silos, it was later renamed in honor of Saint Dominic of Silos, a revered 11th-century abbot whose leadership marked a period of significant spiritual and architectural development. The monastery has since become a symbol of religious and artistic heritage in Spain.

Santo Domingo de Silos Abbey is accessible via three secondary roadways connecting it to major routes: through Aranda de Duero and Lerma to the A-1 highway, and via Hacinas to the N-234. Despite its relative seclusion, it draws scholars, pilgrims, and tourists alike, largely due to its celebrated cloister—considered one of the finest and most iconic examples of Spanish Romanesque architecture. The cloister’s intricate carvings, serene proportions, and historical significance have made it a masterpiece of medieval monastic art. Today, the monastery remains an active Benedictine community and a center for spiritual retreat, known as well for the Gregorian chant recordings by its monks, which have garnered international acclaim.

Origins and Visigothic Beginnings

The origins of the Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos trace back to the 7th century, during the Visigothic period, according to a 15th-century legend. However, the earliest documented evidence of the monastery comes from a charter dated 954, preserved in the monastic archive. At that time, it was known as the Monastery of San Sebastián de Silos.

Development Under Fernán González and Decline Under Almanzor

By the 10th century, during the rule of Count Fernán González of Castile (930–970), the monastery experienced growth and began to flourish. However, this prosperity was disrupted by the devastating military campaigns of Almanzor, the powerful Muslim military leader. His raids led to widespread destruction across Christian territories, and Silos fell into decline and disrepair as a result.

Restoration Under Santo Domingo (1041–1073)

In 1041, the monastery’s fortunes changed when Domingo Manso, a monk from Cañas in La Rioja, arrived under the orders of King Ferdinand I of Castile. Formerly the prior of San Millán de la Cogolla, Domingo had been expelled from Navarre by King García Sánchez III for resisting royal interference in church property. Ferdinand I appointed Domingo as abbot, entrusting him with the task of restoring the ruined monastery. With remarkable energy, holiness, and leadership, Abbot Domingo reorganized the monastic community, rebuilt its infrastructure, and expanded its influence. His contributions were so profound that the monastery was later renamed Santo Domingo de Silos in his honor. Domingo died on December 20, 1073 and was canonized in 1076. His tomb soon became a center of pilgrimage, renowned for reports of miracles.

Romanesque Construction and the Cloister

During Abbot Domingo’s tenure and continuing under his successor Abbot Fortunius, major construction efforts reshaped the monastery. A new Romanesque church was built, featuring a central nave, two side aisles, and five apses. The church was consecrated in 1088, and the monastery’s Romanesque cloister, which survives today, became one of the masterpieces of medieval Spanish art.

Pilgrimage of Juana de Aza and the Birth of Saint Dominic

Around 1170, a Castilian noblewoman named Juana de Aza, pregnant and seeking spiritual support, made a pilgrimage to Silos. She later gave birth to Domingo de Guzmán, founder of the Dominican Order, who was named in honor of Santo Domingo de Silos.

18th-Century Reconstruction: Ventura Rodríguez

By the 18th century, the monastery’s facilities required significant expansion. The famed neoclassical architect Ventura Rodríguez was commissioned to redesign the church. The original Romanesque structure was demolished and replaced with a Baroque-style church laid out in a Greek cross plan, completed in the shape of a square. Although much of the original church was lost, the south wing of the transept and the Puerta de las Vírgenes (Door of the Virgins) leading into the cloister were preserved.

Destruction and Restoration in the 20th Century

In 1970, a fire devastated the monks’ residential quarters. Restoration efforts in 1971–1972 rebuilt the damaged areas, restoring the monastery to its current state. The cloister, however, had remained intact through centuries and retained its Romanesque splendor.

Suppression and Revival: The 19th Century

On November 17, 1835, the Mendizábal Decree—part of the Spanish government’s exclaustration laws—led to the closure of Silos, along with many other monastic houses across Spain. The monastic community was dispersed, and Benedictine life at Silos ceased for 45 years. A revival came in 1880, when a group of Benedictine monks from the Abbey of Saint-Martin de Ligugé in France arrived at Silos. Due to anti-religious laws in France, these monks, led by Dom Ildefonso Guépin of Solesmes, sought refuge in Spain. Their arrival marked the rebirth of monastic life at Silos and prevented its total ruin.

Cultural Legacy and Literary Fame

During a visit to the monastery in the late 19th century, Spanish poet Gerardo Diego composed the acclaimed sonnet El ciprés de Silos (“The Cypress of Silos”), which has become one of the most celebrated poems in Spanish literature.

The Modern Era and Ongoing Influence

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, the Abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos has continued to thrive as a living monastic community. It has gained international fame for its Gregorian chant recordings, which have been widely distributed and appreciated for their spiritual and artistic quality. The monks have also made significant contributions to religious life and culture, founding new monastic houses in Spain—such as Nuestra Señora de Estíbaliz in Álava and San Salvador de Leyre in Navarre—as well as in Latin America, including foundations in Mexico and Argentina.

A Living Legacy

Today, the Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos stands not only as a testament to a thousand years of monastic tradition, but also as a vibrant spiritual center. Its history reflects the rich religious, architectural, and cultural heritage of Castile and León, and it continues to inspire both pilgrims and visitors from around the world.

Architecture of Benedictine Monastery, Santo Domingo de Silos, Spain

Architectural style : Romanesque architecture, Baroque architecture, Neoclassical architecture.

The Two-Storey Cloister and Its Artistic Significance

The two-storey cloister of the Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos stands as a masterpiece of Romanesque art, renowned for its intricate capitals with carved scenes and its sculpted relief panels. This cloister has been extensively studied, notably by the art historian Meyer Schapiro in his seminal work Romanesque Art (1977). The lower cloister is particularly famous for its capitals decorated with fantastic creatures such as dragons, centaurs, lattices, and mermaids. Among its sculptural treasures is also a significant Romanesque free-standing Madonna and Child figure. Remarkably, the cloisters remain the only part of the monastery that has survived without substantial alteration since their original construction.

The cloister is built in a roughly rectangular shape, featuring 16 semi-circular arches on both the north and south sides, and 14 arches on the east and west sides. Construction of the lower storey began in the late 11th century and was completed in the latter half of the 12th century. The dating is supported by an epitaph on the abacus of a group of four capitals in the north gallery, commemorating Santo Domingo who died in 1073. The cloister was formally dedicated on September 29, 1088. The upper storey, built atop the wooden vaulting of the first storey, was finished during the 12th century, completing the architectural ensemble.

Construction History and Style Differences

Abbot Domingo’s successor, Abbot Fortunius, initially oversaw the construction of the north and original west galleries. However, the influx of pilgrims visiting Santo Domingo’s shrine and political and economic challenges between 1109 and 1120 caused a prolonged halt in the building work. This interruption resulted in stylistic differences between the galleries. The east and north galleries were completed first and display a distinct artistic style, while the west and south galleries, finished after construction resumed in 1158, reflect a different workshop’s influence. The second workshop introduced new stylistic approaches, evident in the capitals and reliefs of the later galleries.

Architectural Features: Columns, Arches, and Capitals

The cloister’s architectural framework is composed of paired columns supporting semi-circular arches mounted on a continuous podium that runs along each side. Each arcade contains a central grouping of four columns, enhancing structural rhythm and visual balance. The columns themselves are typically monolithic double shafts approximately 1.15 meters long, except for the central supports in each gallery which are composed of clusters of shafts usually quintuple, except for one unique quadruple twisted column on the north side. The capitals resting atop these columns are unique in decoration, featuring a wide array of motifs including animals, foliage, and abstract designs. In the lower cloister, the capitals are predominantly low-relief carvings of biblical and fantastic scenes, while the capitals on the upper story, created later, portray more narrative scenes due to their later date of creation. The diversity and intricacy of these capitals reflect two different artistic workshops involved in their carving, corresponding to the two main construction phases.

Sculptural Reliefs on the Corner Piers

The four squared corner piers of the cloister serve as key sculptural highlights, each decorated with medium-relief biblical scenes that focus on the Post-Passion narrative of Christ. Originally painted in vivid colors, these reliefs convey important moments in Christian theology: the southeast pier illustrates the Ascension and Pentecost, symbolizing Christ’s glorification and the descent of the Holy Spirit; the northeast pier depicts the Entombment and the Descent from the Cross, emphasizing Christ’s burial; the northwest pier features the Road to Emmaus and Doubting Thomas, themes centered on faith and revelation; while the southwest pier presents the Annunciation to Mary and the Tree of Jesse, both rich in iconographic meaning, representing Christ’s genealogy and divine mission. The reliefs on the first three piers are attributed to the same sculptor who crafted the lower cloister capitals and bear stylistic links to the Abbey of St. Pierre de Moissac in France. In contrast, the southwest pier reliefs are thought to be the work of a second workshop, influenced by the artistic traditions of Galicia, showing stylistic affinities with the sculptural decorations at Santiago de Compostela, particularly in the detailed treatment of drapery and hair.

Symbolism and Function of the Cloister

The cloister functioned as a sacred space for the monastic community—a “paradiso” or earthly paradise, designed to separate the monks from the outside world, often regarded as a realm of evil. The arrangement of fourteen arches on the east and north wings is symbolically significant, representing sacred perfection through the doubling of the number seven. The imagery carved on the capitals and piers stresses the link between heaven and earth, with representations of real and mythical animals and plants intended to inspire spiritual contemplation.

The cloister courtyard features a notable natural symbol: a tall, leafy cypress tree over 130 years old and more than 30 meters high. It stands as an emblem of eternity and transcendence, immortalized in Gerardo Diego’s 1924 poem El ciprés de Silos, where the tree is described as a “lofty fountain of shadow and dream.”

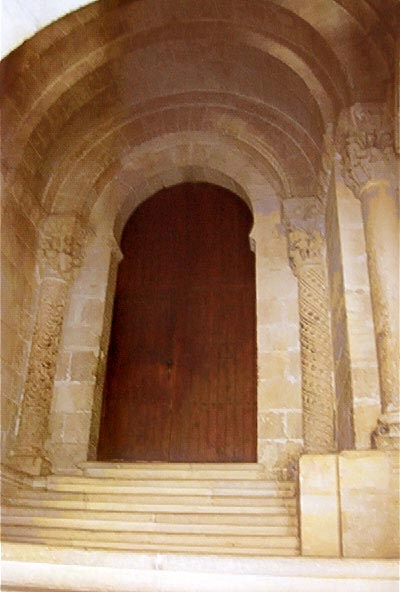

Other Architectural Elements and Monastic Artifacts

The cloister connects to the church through the Puerta de las Vírgenes, a surviving element of the original Romanesque church. The eastern gallery once opened onto a now-lost chapter house, the façade of which is still visible. Additionally, the cloister features a richly decorated Mudejar coffered ceiling, adorned with nearly 700 figures and scenes from 14th- and 15th-century Castile, revealing the monastery’s evolving artistic heritage. Inside the cloister, the cenotaph of Saint Dominic, initially located here after his death in 1073, was later moved to the church. In the 14th century, the tomb was covered by a sepulchral laude supported by three lions bearing the saint’s papal effigy, marking the importance of the abbot’s cult.

The Silos Library and Manuscripts

The monastery’s library was historically one of the main repositories of Mozarabic rite liturgical manuscripts, alongside the Toledo Cathedral library. While many manuscripts were auctioned in 1878, the library still holds treasures such as the Missal of Silos, the oldest Western manuscript written on paper. The abbey’s scriptorium produced significant works, including a richly illuminated Beatus manuscript (a commentary on the Apocalypse), completed in text form in 1091 and illuminated mostly by 1109. This manuscript contains an important medieval map of the Mediterranean and is now housed in the British Library, having left the monastery by the 18th century.

Musical Heritage: From Mozarabic to Gregorian Chant

Originally, the monks sang Mozarabic chant but transitioned to Gregorian chant around the 11th century. The abbey became part of the Solesmes Congregation in 1880, a group renowned for its scholarship and revival of Gregorian chant. The monks of Silos gained international fame for their Gregorian chant recordings, particularly the 1994 album Chant, which reached number three on the Billboard 200 chart and became the best-selling Gregorian chant album ever. While other choirs may surpass them technically, the Silos monks are celebrated for their authentic liturgical singing as part of their daily worship. They are also among the few choirs to have recorded Mozarabic chant, preserving this rare musical tradition.

Feast Day

Feast Day : 20 December

The Benedictine Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos in Spain celebrates its feast day on December 20th, in honor of its founder, Saint Dominic of Silos. Saint Dominic was a key figure in revitalizing monastic life in the region during the 11th century, and his legacy is deeply connected to the monastery’s spiritual and cultural heritage. The feast day is marked by religious ceremonies, special masses, and community gatherings that pay tribute to the saint’s contributions and the enduring significance of the monastery in Spanish religious history.

Church Mass Timing

Monday to Saturday : 9:00 AM

Sunday : 11:00 AM

Church Opening Time:

Monday to Saturday : 10:00 AM – 1:00 PM, 4:30 PM – 6:00 PM

Sunday : 12:00 PM – 1:00 PM, 4:30 PM – 6:00 PM

Contact Info

Address : Benedictine Monastery

Santo Domingo, 1, 09610 Santo Domingo de Silos, Burgos, Spain.

Phone : +34 947 39 00 49

Accommodations

Connectivities

Airway

Benedictine Monastery, Santo Domingo de Silos, Spain, to Burgos Airport, distance 54 min (64.9 km) via BU-901 and N-234.

Railway

Benedictine Monastery, Santo Domingo de Silos, Spain, to Estación de autobuses de Lerma C. de la Estación, distance between 29 min (31.5 km) via BU-900.